写在一开始

译者说明 / Translator Note

本书翻译自picp-pico原项目,加入了一些译者的想法作为补充。译者是一名拥有 1 年嵌入式开发经验的独立开发者。由于水平有限,翻译过程中难免存在疏漏或不当之处。

如果您在阅读过程中发现任何问题(如翻译错误、技术偏差等),欢迎通过以下方式反馈,您的建议对我非常重要:

🌟 原项目仓库 / Original Repository

点击上方按钮前往原项目仓库,为原作者点个 Star 吧!

Please visit the original repository and give it a star!

Pico Pico - 简介

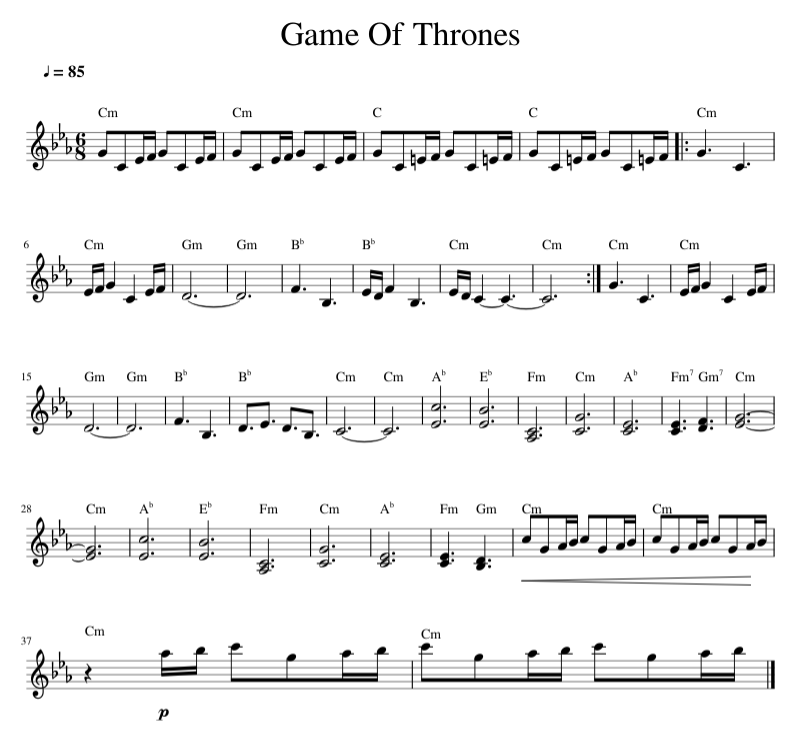

在本书中,我们将使用 Raspberry Pi Pico 2,并使用 Rust 编程来探索各种有趣的项目。你将完成的练习包括:调暗 LED、控制舵机、使用超声波传感器测距、在 OLED 显示屏上显示 Ferris(🦀)图像、使用 RFID 读卡器、用蜂鸣器演奏歌曲、在室内光线不足时点亮 LED、测量温度等。

认识硬件 - Pico 2

我们将使用的板子是基于新款 RP2350 芯片的 Raspberry Pi Pico 2。它提供双核灵活性,既支持 ARM Cortex-M33 内核,也可选用 Hazard3 RISC‑V 内核。默认情况下使用 ARM 内核,但开发者可根据需要尝试 RISC‑V 架构。

可在官方网站查看更详细的信息。

注意:还有一代使用 RP2040 的旧款 Raspberry Pi Pico。本书使用的是更新的 Pico 2(搭载 RP2350)。购买硬件时请确认型号!

还有一个带 Wi‑Fi 和蓝牙功能的变体 Pico 2 W,同样基于 RP2350,但与本书示例并非完全兼容。如希望直接按本书操作而不做额外修改,建议选择标准的非无线版本 Pico 2。

可选硬件:Debug Probe

Raspberry Pi Debug Probe 能让向 Pico 2 烧录固件的过程更加便捷。没有调试器时,每次上传新固件都需按住 BOOTSEL 按钮。调试器同时提供完善的调试支持,非常实用。

该工具为可选项。除专门介绍调试器的章节外,本书的其它内容均可在没有调试器的情况下学习。我在刚开始接触 Pico 时也是先不使用调试器,随后才购入。

如何选择?

如果预算有限,可以暂时不购买,因其价格大约为一块 Pico 2 的两倍;若成本不是问题,则非常值得入手。如有第二块 Pico,也可将其配置成低成本的调试器。

数据手册

如需更详细的技术信息、规格与指南,请查阅官方数据手册:

许可协议

Pico Pico(本项目)按以下许可分发:

- 代码示例及独立的 Cargo 项目同时遵循 MIT License 与 Apache License v2.0。

- 本书的文字内容遵循 Creative Commons CC-BY-SA v4.0 许可协议。

支持本项目

你可以通过在 GitHub 上为该项目加星,或把本书分享给他人来支持它 😊

免责声明

本文档中分享的实验与项目均由作者实践验证,但结果可能存在差异。实验过程中产生的任何问题或损坏,作者不承担责任。请谨慎操作并采取必要的安全措施。

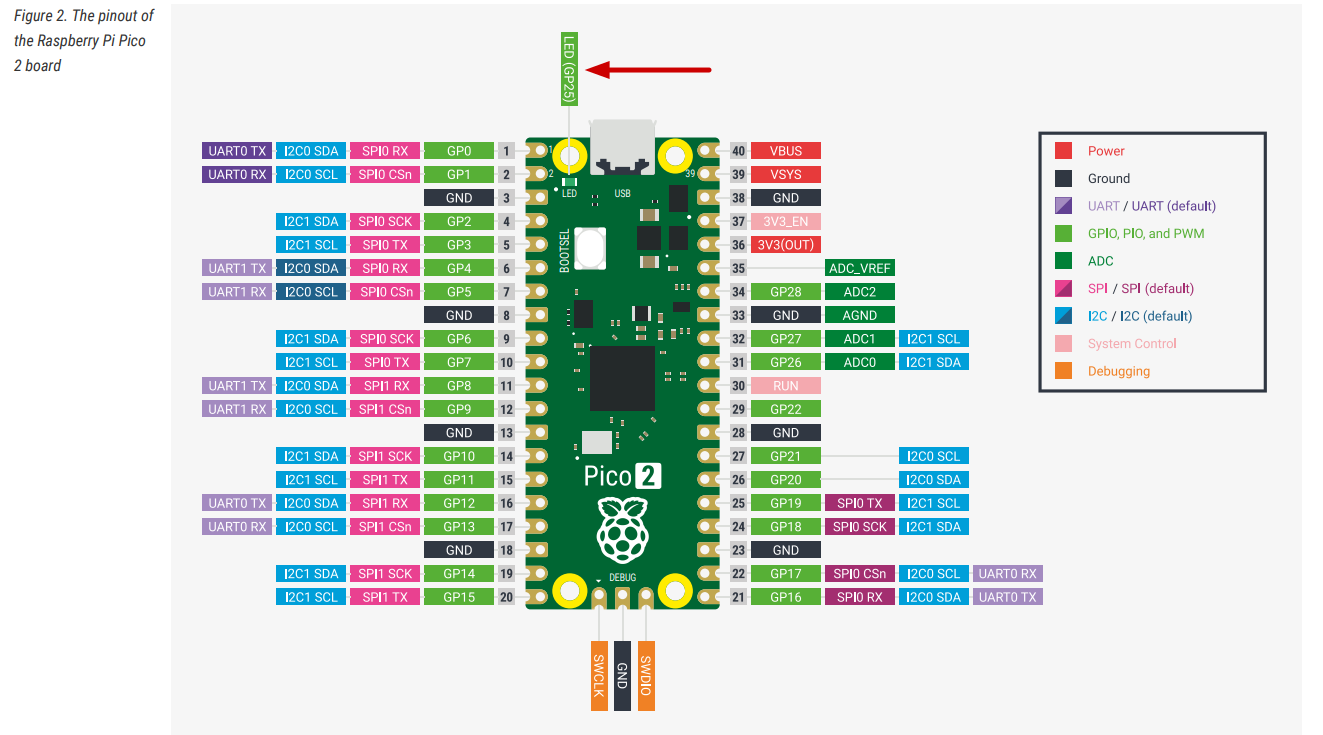

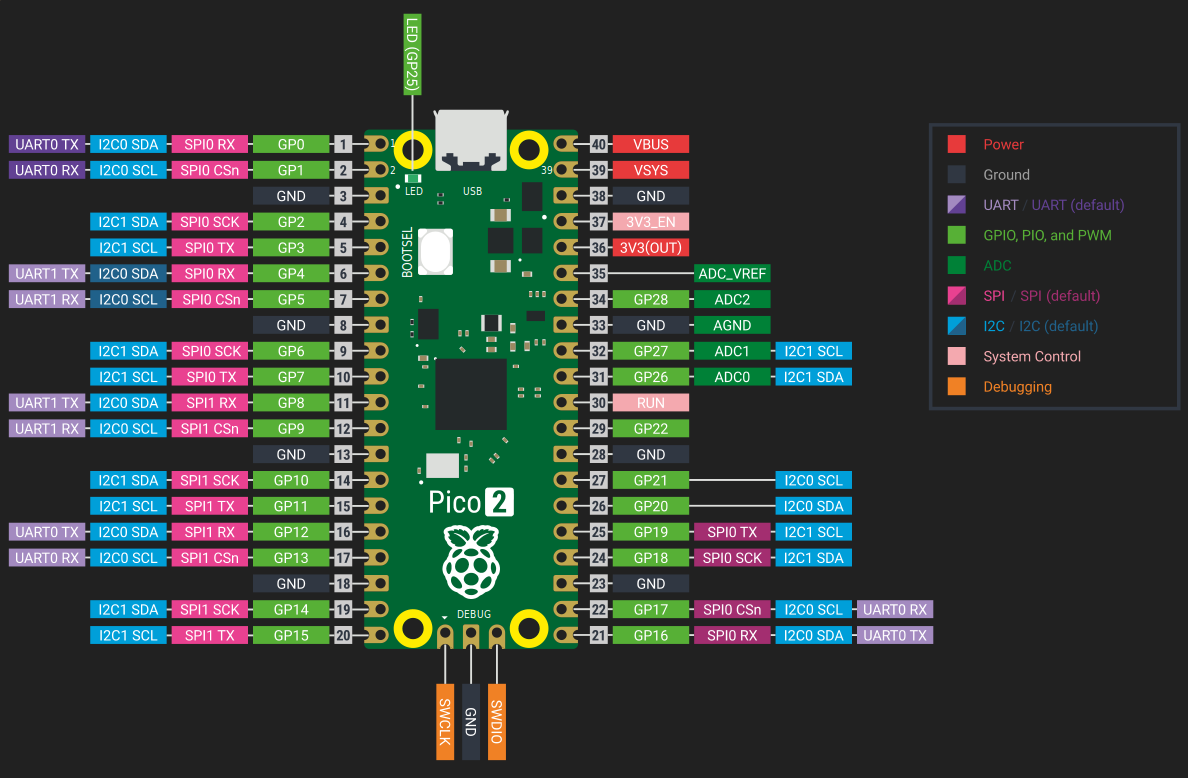

Raspberry Pi Pico 2 引脚图

注意: 现在无需记住或理解每一个引脚。在完成本书的练习时,我们会随时回到这一节。

电源引脚

电源引脚对 Raspberry Pi Pico 2 至关重要,它们既为开发板供电,也为连接的传感器、LED、马达等外设提供电力。

Pico 2 具有如下电源引脚。它们在引脚图中以红色(电源)和黑色(地)标记,可用于为板子或外部器件供电。

-

VBUS 连接到来自 USB 端口的 5V。当通过 USB 供电时,该引脚大约为 5V。它可用于为小型外设供电,但不适合大电流负载。

-

VSYS 是板子的主电源输入,可连接电池或稳压电源,电压范围为 1.8V 到 5.5V。该引脚为板载 3.3V 稳压器供电,进而为 RP2350 等部件供电。

-

3V3(OUT) 提供来自板载稳压器的稳定 3.3V 输出,可用于为传感器或显示屏等外设供电,但建议将电流限制在 300mA 以内。

-

GND 引脚用于完成电路并连接到系统接地。Pico 2 在板上提供多个 GND 引脚,便于连接外设时接地。

GPIO 引脚

当你希望微控制器(例如 Pico)与外界交互,如点亮灯、读取按键、感知温度或控制电机时,就需要通过 GPIO 引脚连接这些外部器件。GPIO 引脚就是 Raspberry Pi Pico 2 与外设之间的连接点。

Pico 2 提供 26 个通用输入/输出(GPIO)引脚,标号为 GPIO0 到 GPIO29,尽管并非所有标号都在排针上暴露。这些引脚高度灵活,可用于读取开关或传感器等输入,也可用于控制 LED、马达等输出。

所有 GPIO 的逻辑电平为 3.3V。因此接入的输入信号不应超过 3.3V,否则可能损坏开发板。许多 GPIO 支持基础的数字 I/O,部分引脚还支持模拟输入(ADC),或可配置为 I2C、SPI、UART 等通信线路。

引脚编号

每个 GPIO 引脚有两种标识方式:软件中使用的 GPIO 编号和开发板上的物理引脚位置。编写代码时使用 GPIO 编号(例如 GPIO0);实际连线时需确认该编号对应的物理针脚。

GPIO25 比较特殊,它连接到板载 LED,可以直接在代码中控制,而无需外接布线。

例如,当代码中引用 GPIO0 时,在硬件上应将导线连接到物理引脚 1;GPIO2 对应物理引脚 4。

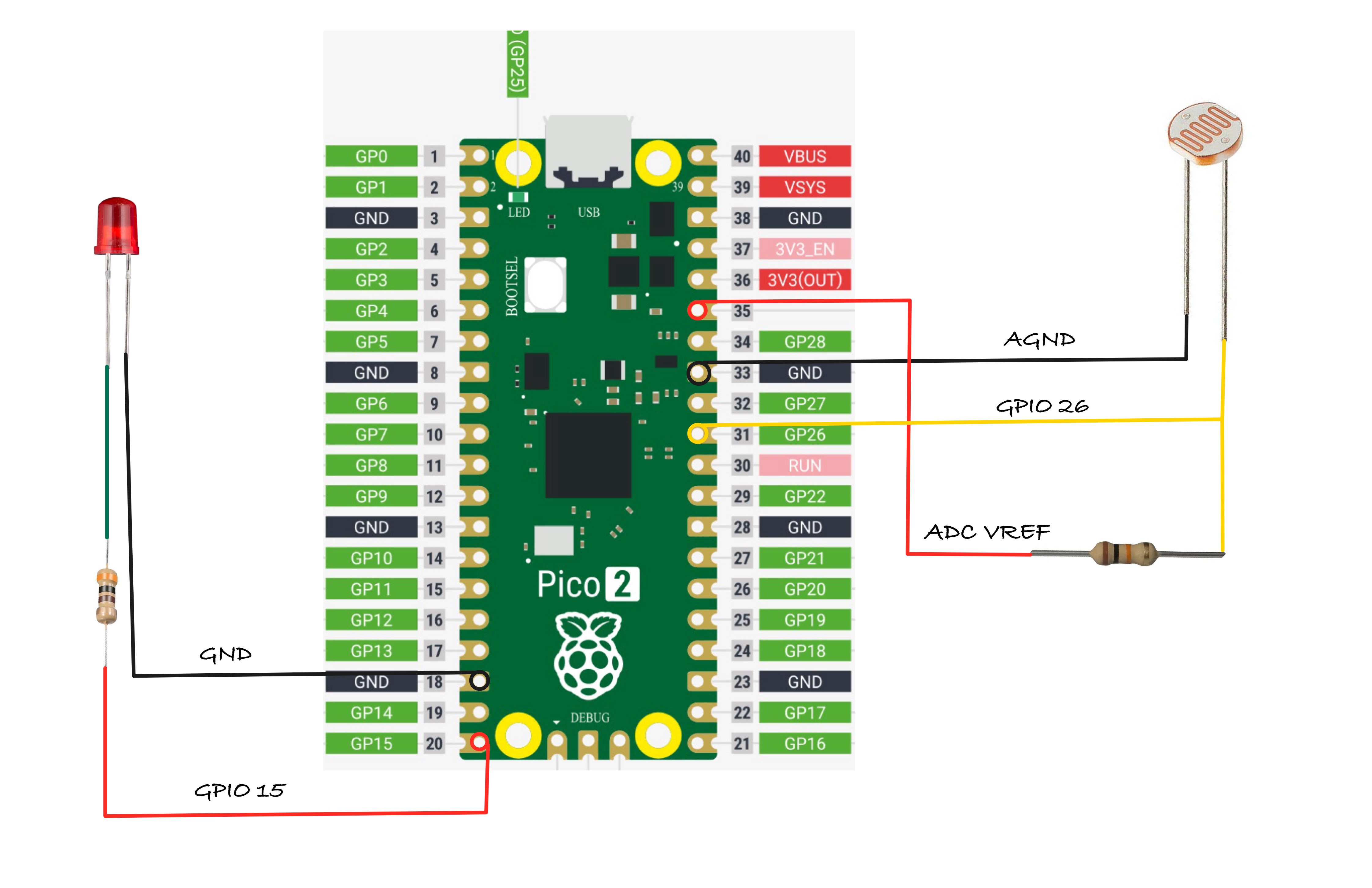

ADC 引脚

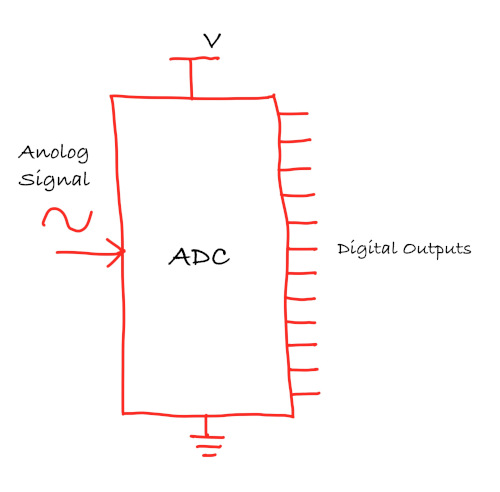

Pico 2 上的大多数引脚只能处理简单的开/关信号,适合控制 LED 或读取按钮。但如果你想测量房间亮度以自动点亮灯、监测土壤湿度或读取旋钮转动角度,这些任务需要能够感知连续变化的信号,而非仅有高低电平。

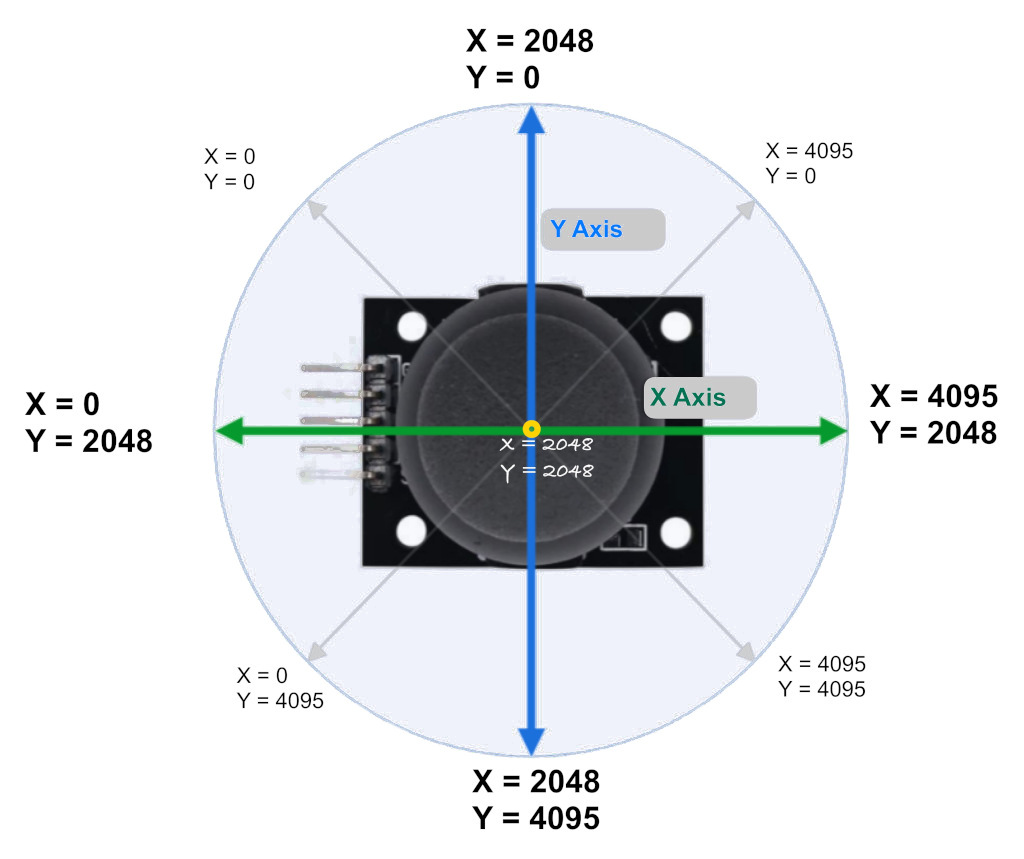

为此,需要使用 ADC(模数转换器)引脚。ADC(Analog-to-Digital Converter)会将模拟电压转换为程序可读的数字值。例如 0V 对应 0,3.3V 对应 4095(12 位分辨率的最大值)。本书后文会详细介绍 ADC 的使用。

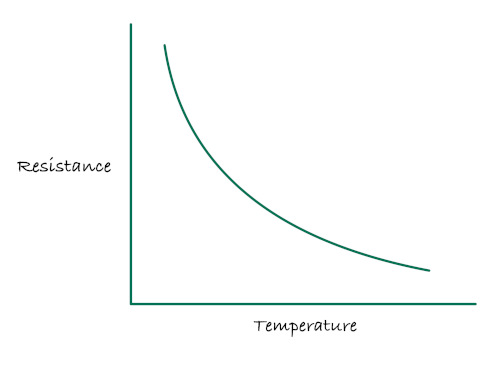

Pico 2 有三个支持 ADC 的引脚,分别是 GPIO26、GPIO27 和 GPIO28,对应 ADC0、ADC1、ADC2。这些引脚可用于读取光敏、电阻式传感器等模拟信号。

此外还有两个与模拟输入相关的特殊引脚:

-

ADC_VREF 是 ADC 的参考电压。默认连接到 3.3V,意味着 ADC 会把 0V 到 3.3V 映射到数字范围内;你也可以输入其它参考电压(例如 1.25V)以在特定电压范围内获得更高分辨率。

-

AGND 是模拟地,用于为模拟信号提供更干净的接地参考,有助于降低噪声并提高测量精度。使用模拟传感器时,建议将其地连接到 AGND 而不是普通 GND。

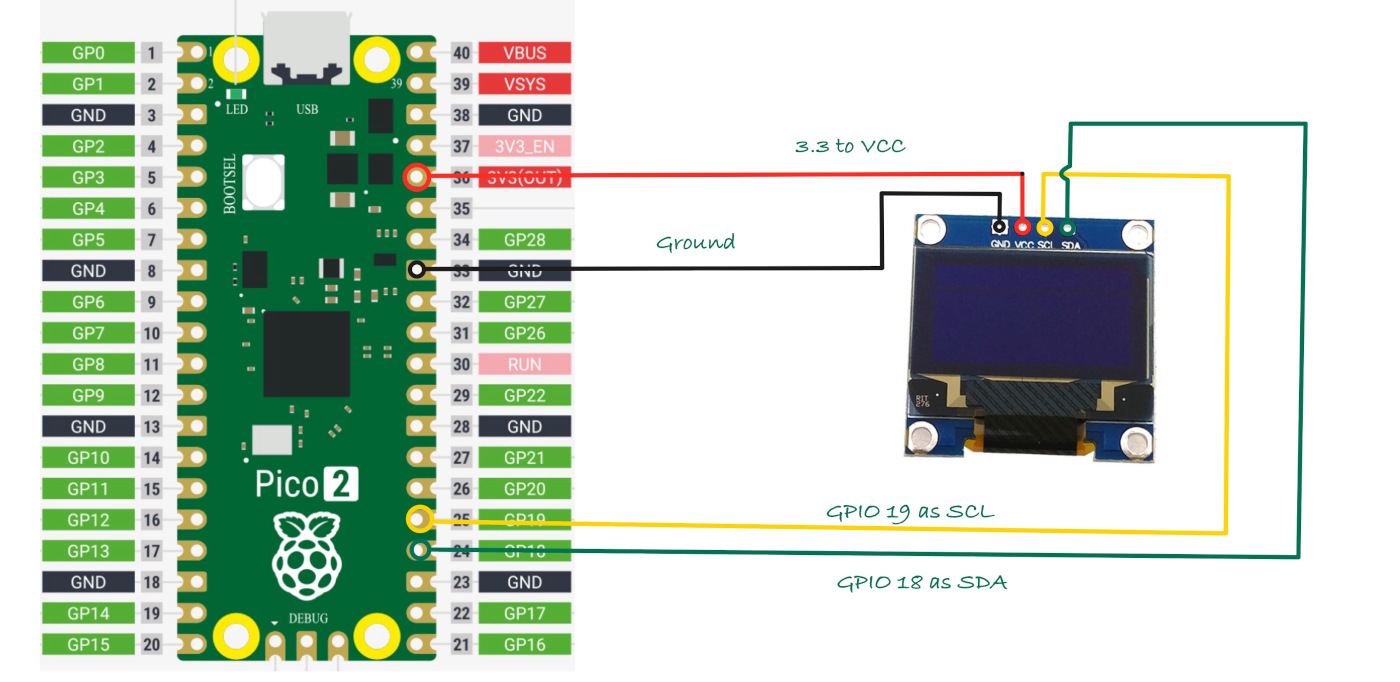

I2C 引脚

Pico 2 支持 I2C,总线仅需两根线即可连接多个设备,常用于传感器、显示屏等外设。

I2C 使用两条信号线:SDA(数据)和 SCL(时钟)。所有设备共享这两条线,每个设备有唯一地址,Pico 2 可通过同一对线与多个设备通信。

Pico 2 提供两个 I2C 控制器:I2C0 与 I2C1。每个控制器可以映射到多组 GPIO,引脚选择更灵活。

-

I2C0 可使用如下 GPIO:

- SDA(数据):GPIO0、GPIO4、GPIO8、GPIO12、GPIO16 或 GPIO20

- SCL(时钟):GPIO1、GPIO5、GPIO9、GPIO13、GPIO17 或 GPIO21

-

I2C1 可使用如下 GPIO:

- SDA(数据):GPIO2、GPIO6、GPIO10、GPIO14、GPIO18 或 GPIO26

- SCL(时钟):GPIO3、GPIO7、GPIO11、GPIO15、GPIO19 或 GPIO27

需从同一控制器中选择匹配的 SDA/SCL 对。

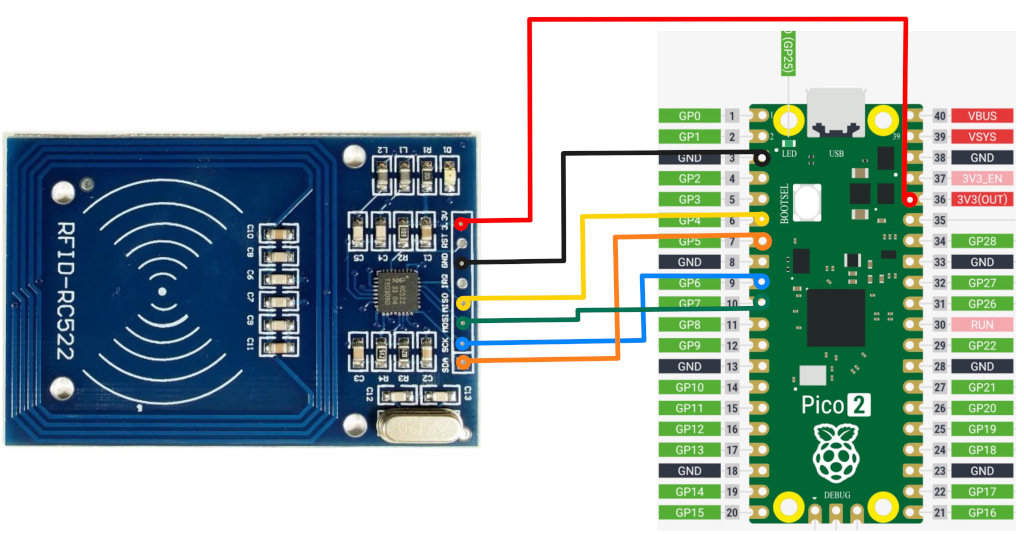

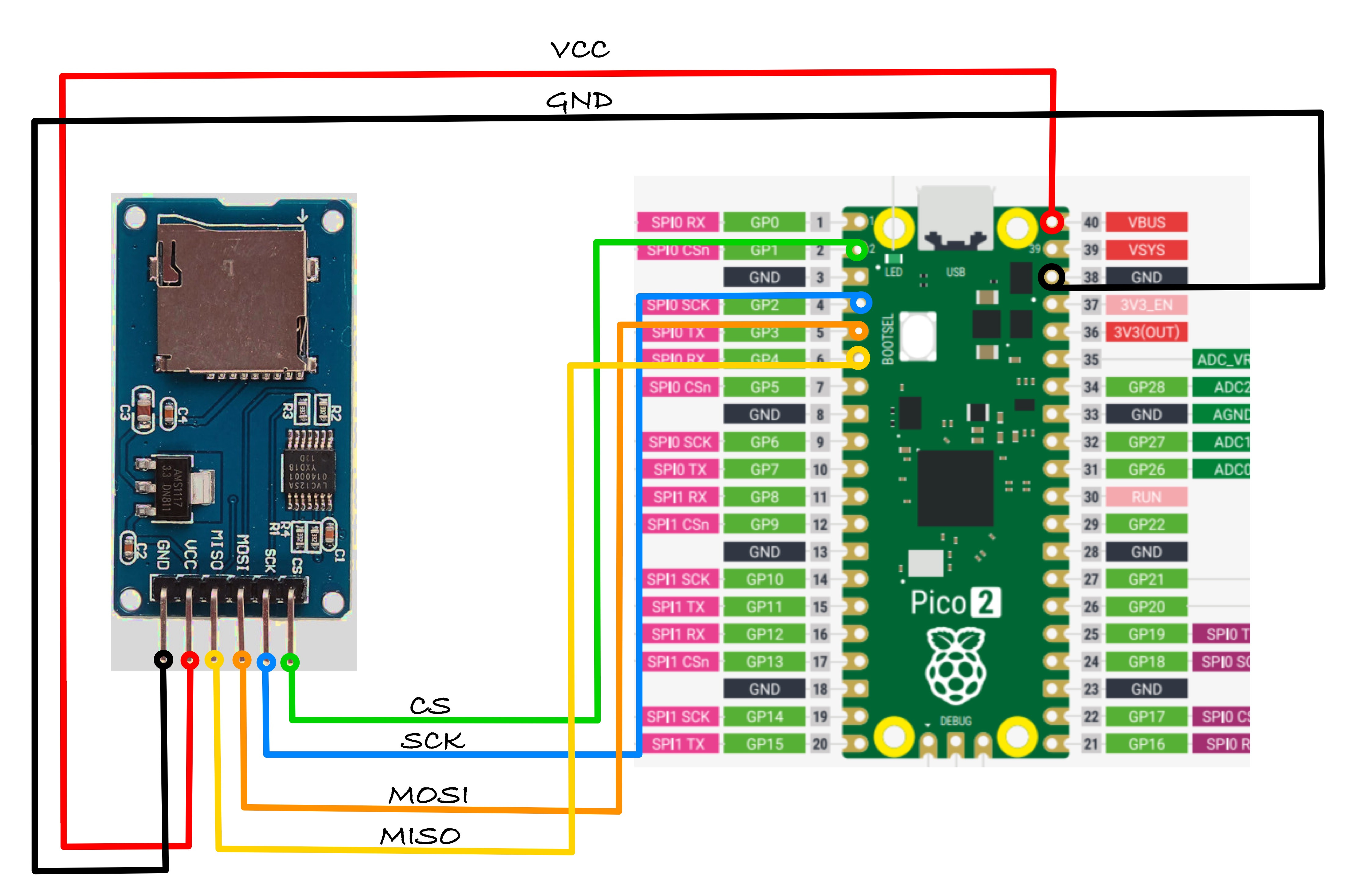

SPI 引脚

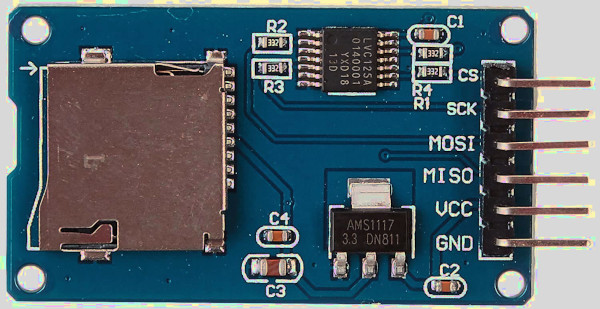

SPI(串行外设接口)是另一种常用通信协议,适合连接显示屏、SD 卡和部分传感器。与 I2C 相比,SPI 使用更多线但速度更快,通常由一个控制器与一个或多个设备通信。

SPI 使用四条主要信号:

- SCK(时钟):控制数据传输节奏;

- MOSI(主出从入):控制器到设备的数据;

- MISO(主入从出):设备返回给控制器的数据;

- CS/SS(片选):由控制器指定要通信的目标设备。

在 Pico 2 的引脚图中,MOSI 标记为 Tx,MISO 标记为 Rx,CS 标记为 Csn。

Pico 2 提供 SPI0 与 SPI1 两个控制器,可映射到多组 GPIO:

-

SPI0 可使用:

- SCK:GPIO2、GPIO6、GPIO10、GPIO14、GPIO18

- MOSI:GPIO3、GPIO7、GPIO11、GPIO15、GPIO19

- MISO:GPIO0、GPIO4、GPIO8、GPIO12、GPIO16

-

SPI1 可使用:

- SCK:GPIO14、GPIO18

- MOSI:GPIO15、GPIO19

- MISO:GPIO8、GPIO12、GPIO16

可根据电路布局从同一控制器中选择兼容的一组引脚。CS(片选)不固定,可以使用任意空闲 GPIO。稍后章节会介绍如何配置 SPI 并连接外设。

UART 引脚

UART(通用异步收发传输器)是最简单的串行通信方式之一,仅需两条主线:

- TX(发送):输出数据;

- RX(接收):输入数据;

UART 常用于连接 GPS 模块、蓝牙适配器或与电脑通信以进行调试。

Pico 2 提供两个 UART 控制器:UART0 与 UART1。每个控制器都能映射到多组 GPIO,布线更灵活。

-

UART0 可使用:

- TX:GPIO0、GPIO12、GPIO16

- RX:GPIO1、GPIO13、GPIO17

-

UART1 可使用:

- TX:GPIO4、GPIO8

- RX:GPIO5、GPIO9

需成对使用同一 UART 控制器的 TX 与 RX。例如,可选择 UART0 的 GPIO0(TX)和 GPIO1(RX),或 UART1 的 GPIO8(TX)和 GPIO9(RX)。

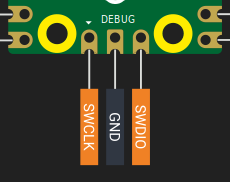

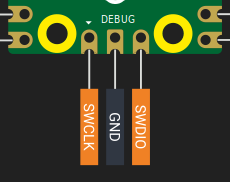

SWD 调试引脚

Pico 2 提供专用的 3 针 SWD(Serial Wire Debug)调试接口,这是 ARM 标准的调试方式,能用于刷写固件、查看寄存器、设置断点和实时调试。

该接口包含:

- SWDIO:串行数据线

- SWCLK:串行时钟线

- GND:地参考

这些引脚不与 GPIO 复用,位于板底独立的调试排针上。通常需要借助 Raspberry Pi Debug Probe、CMSIS-DAP 适配器或其它兼容工具(如 OpenOCD、probe-rs)连接这些引脚。

板载温度传感器

Pico 2 内置一个温度传感器并内部连接到 ADC4。你可以像读取外部模拟传感器一样,通过 ADC 获取芯片温度。

该传感器测量的是 RP2350 芯片本身的温度,在芯片负载较高时可能高于室温,不能准确反映环境温度。

控制引脚

这些引脚用于控制开发板的电源行为,可用于复位或关闭芯片。

-

3V3(EN) 是板载 3.3V 稳压器的使能引脚,将其拉低会关闭 3.3V 电源轨,从而使 RP2350 关闭。

-

RUN 是 RP2350 的复位引脚,内部有上拉电阻,默认为高电平,拉低即复位芯片。可用于连接物理复位按钮或由其它设备触发复位。

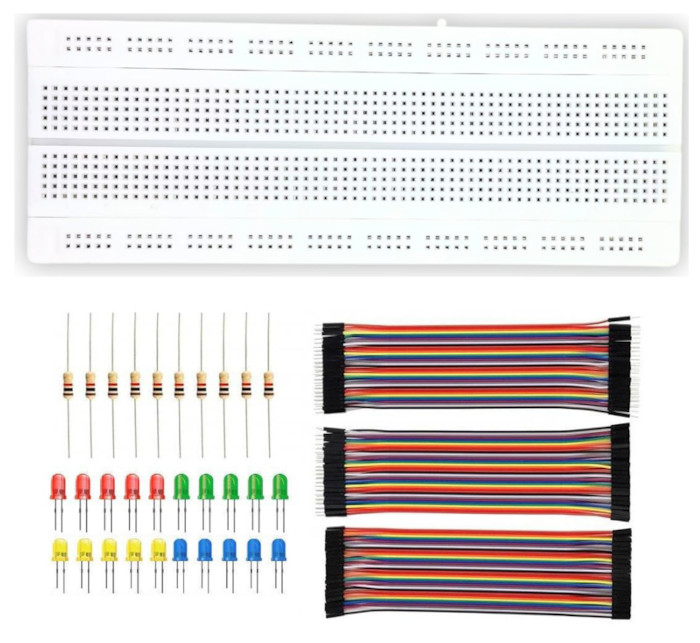

附加硬件

在本节中,我们将了解在使用 Raspberry Pi Pico 时可能会用到的一些额外硬件。

电子套件

你可以从基础电子套件开始,或在需要时购买元件。只要包含电阻、杜邦线和面包板,一个简单且低成本的套件就足以入门。这些物品在整个课程中都会用到。

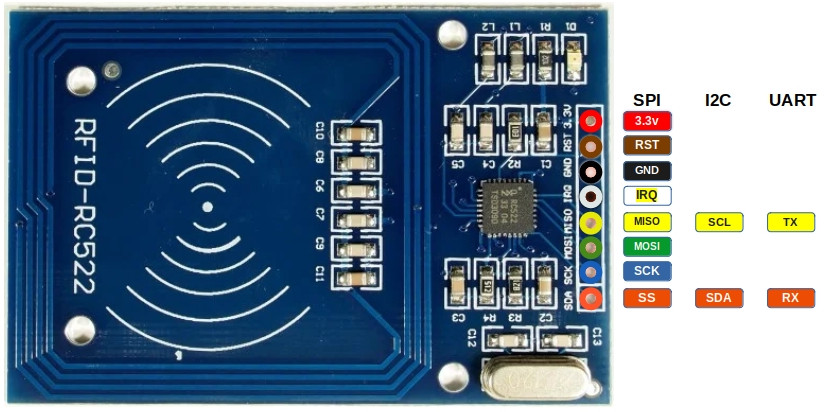

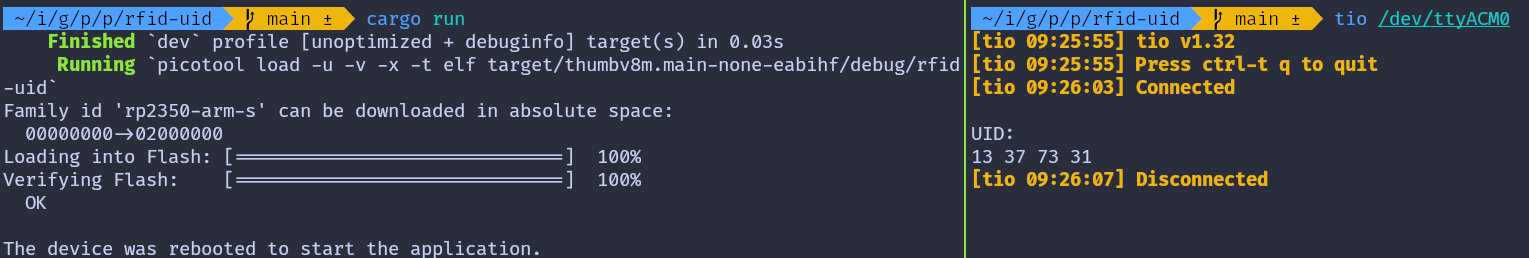

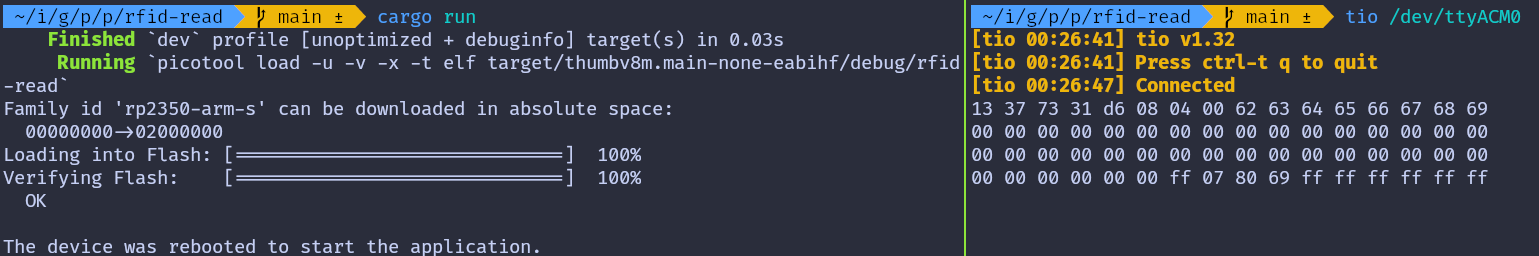

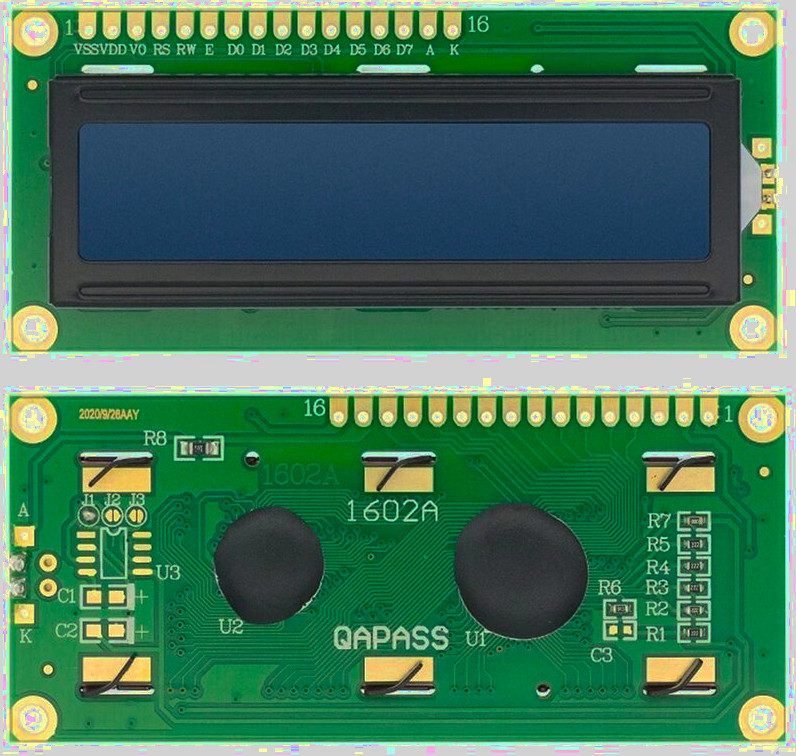

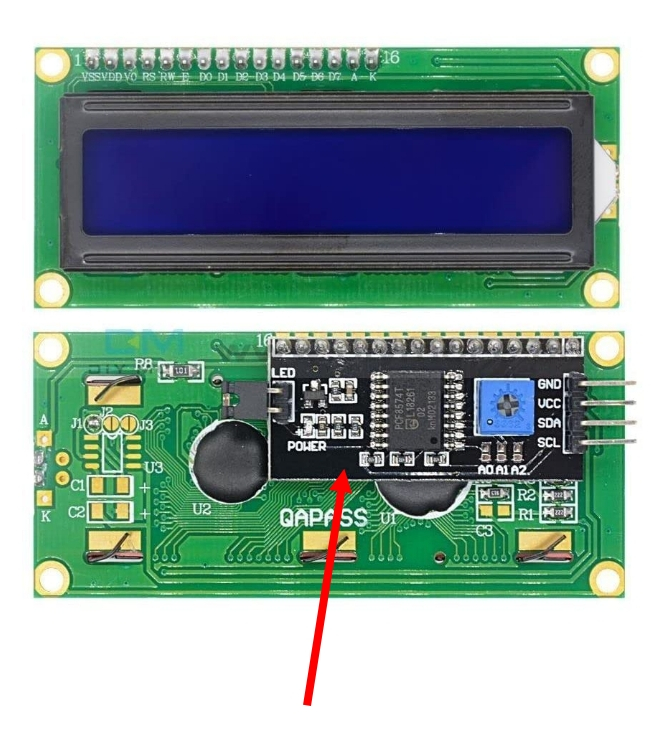

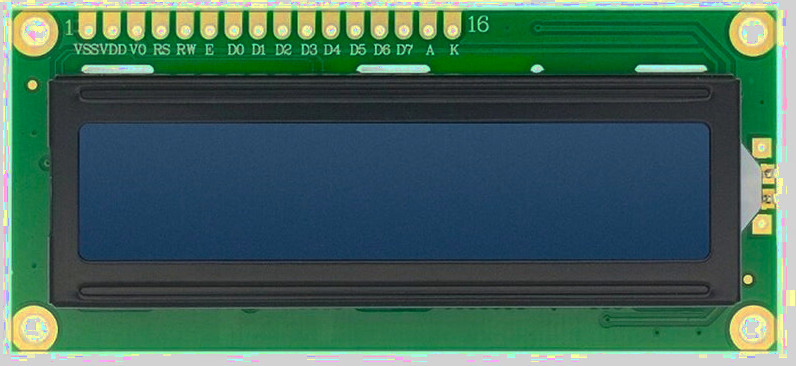

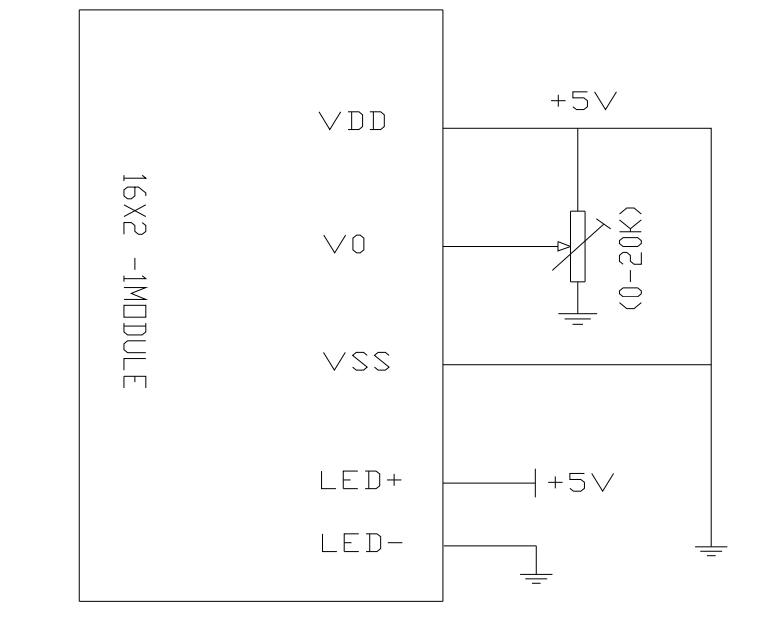

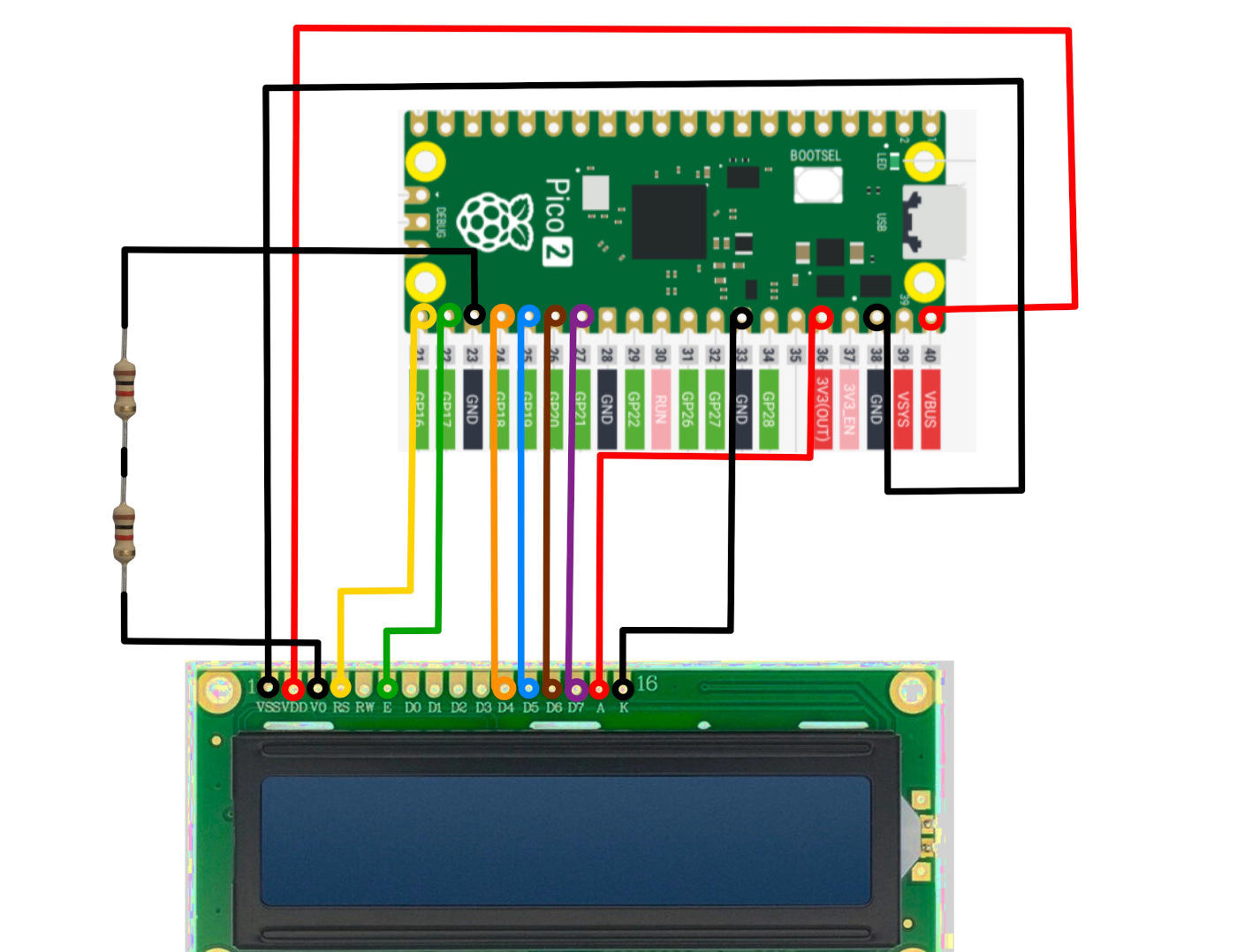

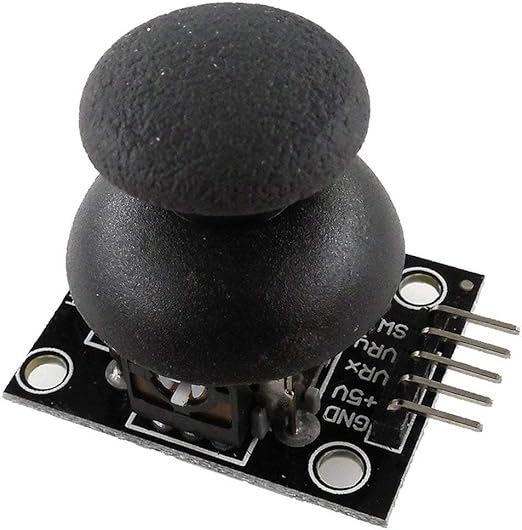

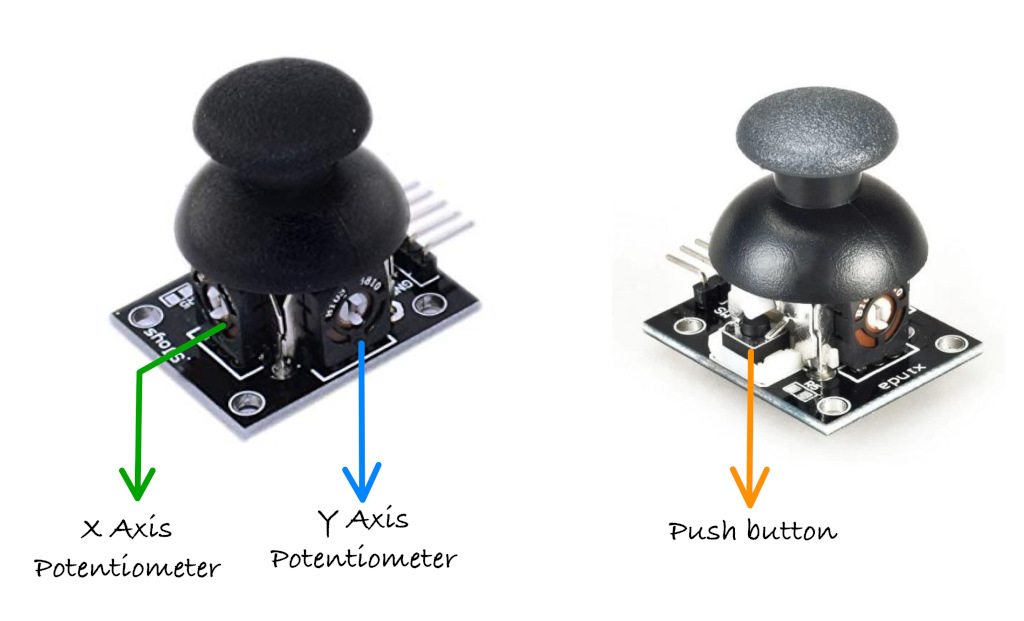

本书使用的其他元件包括 LED、HC SR04 超声波传感器、有源和无源蜂鸣器、SG90 微型舵机、LDR、NTC 热敏电阻、RC522 RFID 读卡器、micro SD 卡适配器、HD44780 显示屏以及摇杆模块。

可选硬件:Debug Probe

Raspberry Pi Debug Probe 让为 Pico 2 刷写固件变得容易得多。如果没有它,每次想上传新固件时都必须按下 BOOTSEL 按钮。该调试器还提供完善的调试支持,非常有用。

该工具是可选的。你可以在没有它的情况下完成整本书(与 debug probe 相关的部分除外)。我最初使用 Pico 时没有调试器,后来才购买了它。

如何决定?

如果预算紧张,可以暂时跳过它,因为其价格大约是 Pico 2 的两倍。如果成本不是问题,它是一次不错的购买,而且非常方便。如果你有第二块 Pico,也可以将其用作低成本的 debug probe。

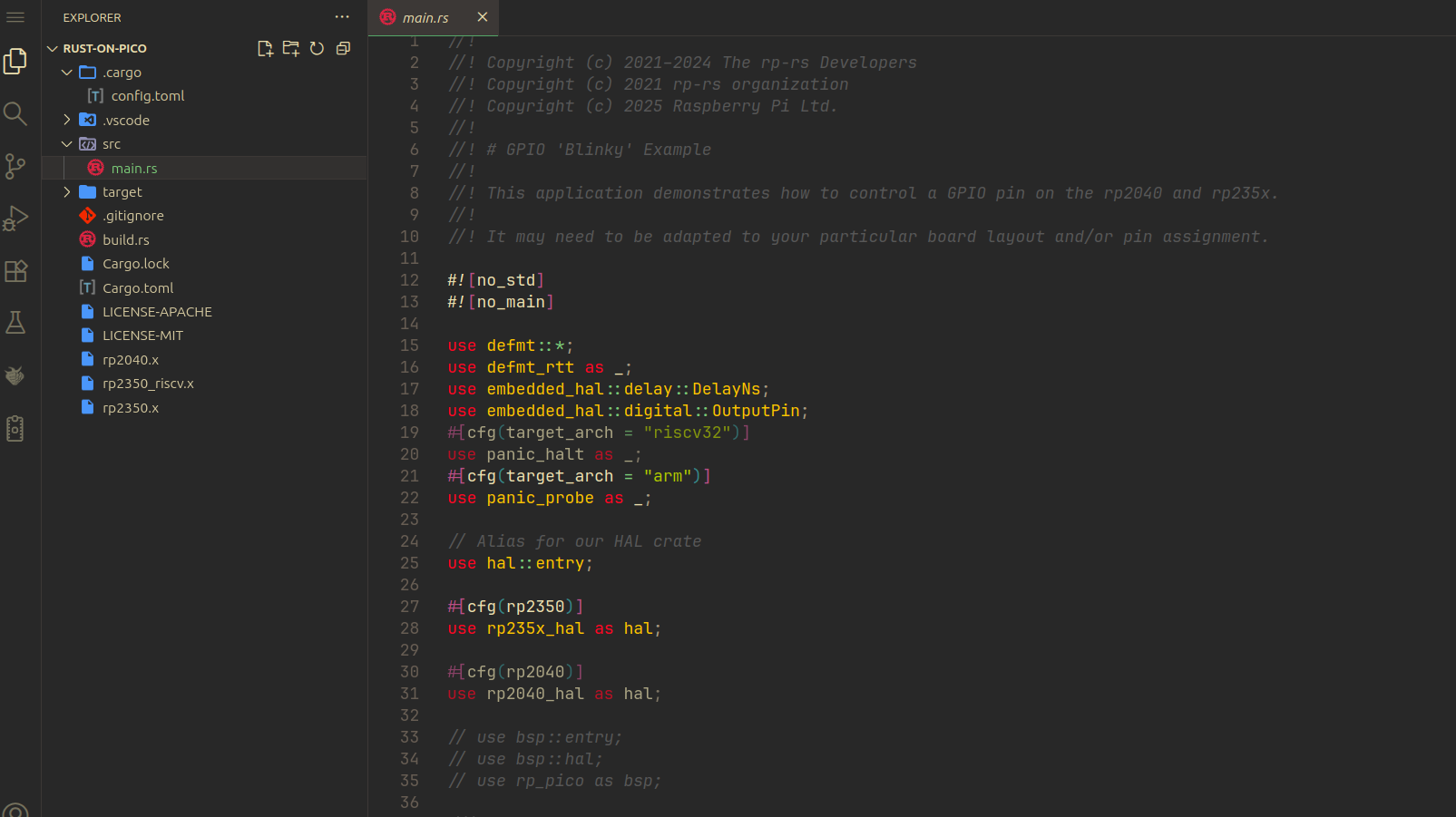

演示:vscode/nvim上进行嵌入式开发

视频?图文?

当我完整的学完且体会完成了这个部分我再过来写这个体会

环境配置

安装 Rust

本书示例基于 Rust 工具链开发,推荐使用官方的 rustup 安装器完成配置。

- Windows:访问 https://win.rustup.rs/ 下载并运行

rustup-init.exe,按提示选择默认安装。 如提示缺少构建工具,可先安装 Visual Studio Build Tools。 - Linux:使用官方脚本安装:

curl --proto '=https' --tlsv1.2 -sSf https://sh.rustup.rs | sh - macOS:可以同样使用官方脚本,或先通过 Homebrew 安装基础依赖后再运行 rustup:

/bin/bash -c "$(curl -fsSL https://sh.rustup.rs)"

安装完成后,重启终端并确认版本:

rustc --version

cargo --version

如果之前安装过旧版本,可执行 rustup update 升级。

之后,你还可以使用 rustup 命令来安装 Rust 和 Cargo 的测试版(beta)或 nightly 版本。

Picotool

picotool 是一个用于操作 RP2040/RP2350 二进制文件的工具,在设备进入 BOOTSEL 模式时可与其交互。

你也可以直接从 这里 下载 SDK 工具的预编译版本,这通常比按步骤构建更为简单。

下面是我采用的快速安装步骤摘要:

# 安装依赖

sudo apt install build-essential pkg-config libusb-1.0-0-dev cmake

mkdir embedded && cd embedded

# 克隆 Pico SDK

git clone https://github.com/raspberrypi/pico-sdk

cd pico-sdk

git submodule update --init lib/mbedtls

cd ../

# 设置 Pico SDK 的环境变量

PICO_SDK_PATH=/MY_PATH/embedded/pico-sdk

# 克隆 Picotool 仓库

git clone https://github.com/raspberrypi/picotool

编译并安装 Picotool:

cd picotool

mkdir build && cd build

# cmake ../

cmake -DPICO_SDK_PATH=/MY_PATH/embedded/pico-sdk/ ../

make -j8

sudo make install

在 Linux 上,你可以添加 udev 规则以便无需 sudo 即可运行 picotool:

cd ../

# 在 picotool 克隆目录下

sudo cp udev/60-picotool.rules /etc/udev/rules.d/

Rust 目标三元组

要为 RP2350 芯片构建并部署 Rust 代码,需要添加相应的目标:

rustup target add thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf

rustup target add riscv32imac-unknown-none-elf

probe-rs —— 烧录与调试工具

probe-rs 是一套现代的、原生 Rust 的嵌入式烧录与调试工具链,它同时支持 ARM 与 RISC-V 平台,并可以直接与硬件调试器配合使用。对于使用 Debug Probe 的 Pico 2,probe-rs 是进行烧录和调试的常用工具。

使用官方安装脚本安装 probe-rs:

curl -LsSf https://github.com/probe-rs/probe-rs/releases/latest/download/probe-rs-tools-installer.sh | sh

有关最新安装说明,请参考 probe-rs 官方文档。

默认情况下,Linux 上的调试器只能由 root 访问。为了避免每次都使用 sudo,建议安装相应的 udev 规则,使普通用户也能访问调试器。请按照此处的步骤进行配置。

快速摘要:

- 从 probe-rs 仓库下载 udev 规则文件(69-probe-rs.rules)

- 将其复制到

/etc/udev/rules.d/ - 使用

sudo udevadm control --reload重新加载规则 - 拔掉并重新插入 Debug Probe

完成上述配置后,你就可以在无需 root 权限的情况下使用 probe-rs 了。

快速上手

在详细讲解原理之前,我们先直接动手操作:用一段简单的代码点亮 Pico 2 的板载 LED。

我们将使用 Embassy,这是为像 Raspberry Pi Pico 2 这样的微控制器设计的 Rust 框架。Embassy 允许你编写异步(async)代码,能同时处理多个任务,例如在读取按键的同时让 LED 闪烁,而不会阻塞其他任务的执行。

下面的代码通过在高电平(点亮)和低电平(熄灭)之间切换引脚输出实现闪烁效果。如引脚图所述,Pico 2 的板载 LED 连接在 GPIO25。本程序将该引脚配置为输出(当我们需要控制 LED、驱动电机或向其他设备发送信号时使用输出模式),并把初始状态设为低电平(关闭)。

代码片段

此处仅展示 main 函数的代码。要让它完整运行,还需引入依赖并完成初始化,这些内容将在下一章深入讲解。现在我们主要体验运行效果。你可以克隆我提供的快速上手项目并立即运行。

注意:此代码不适用于 Pico 2 W 版本。Pico 2 W 的

GPIO25用于无线接口控制,若需控制板载 LED,需要采用不同的方法。

#[embassy_executor::main] async fn main(_spawner: Spawner) { let p = embassy_rp::init(Default::default()); // 板载 LED 实际上连接在引脚 25 let mut led = Output::new(p.PIN_25, Level::Low); loop { led.set_high(); // <- 点亮 LED Timer::after_millis(500).await; led.set_low(); // <- 熄灭 LED Timer::after_millis(500).await; } }

克隆快速上手项目

git clone https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-quick

cd pico2-quick

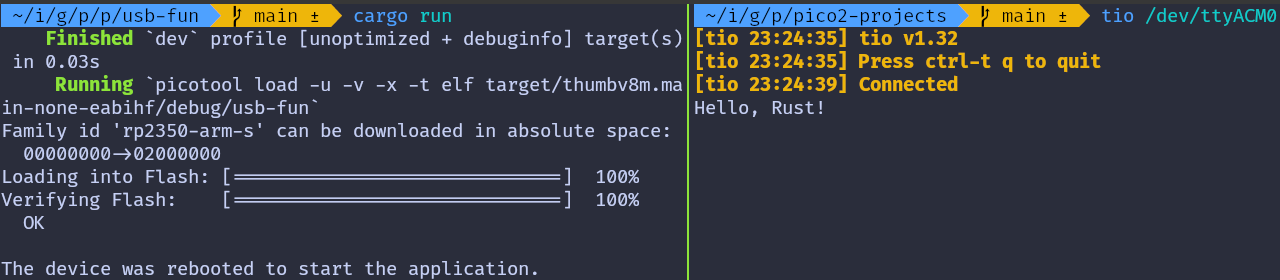

如何运行?

要把程序刷入 Pico 2,请按住 BOOTSEL 按钮,同时使用 Micro USB 数据线将其连接到电脑。USB 插好后即可松开按钮。

# 运行程序

cargo run

该命令会把程序写入 Pico 2 的闪存并自动运行。如果成功,你会看到板载 LED 按固定间隔闪烁。若出现错误,请检查开发环境与硬件连接是否正确;若仍无法解决,请在 GitHub 提交 issue 并附上详细信息,以便我改进本指南。

一切的开始—cargo

Cargo简介

Cargo:Rust的包管理工具 Cargo 是 Rust 语言的官方包管理器。它负责下载你的 Rust 项目的依赖库,编译你的代码,生成可执行的包,并将这些包上传到 crates.io——Rust 社区的官方包仓库。

在“快速上手”章节中,我们使用 cargo 指令将示例刷写到 Pico 2 中:

- 克隆示例仓库并进入目录。

- 将 Pico 2 按住 BOOTSEL 后通过 USB 连接电脑,松开按键让设备进入可写模式。

- 执行

cargo run,cargo 会根据项目配置完成编译,并通过预设的 runner 将生成的镜像写入 Pico 2。 - 烧录完成后,板载 LED 会按固定频率闪烁。

这个流程展示了 cargo 在嵌入式项目中的常见用法:一条命令同时完成构建与烧录,便于快速迭代。[这里补充C语言中是怎么进行的?]

!后续再慢慢进行优化吧,现在体会还不算太深入,一定要边进行C开发,一遍进行Rust开发,两者结合着来进行学习

Cargo run都干啥了

cargo 在 pico2-quick 项目中串起了从编译到烧录的完整链路:

- 目标与运行器:

- 构建脚本:

build.rs在编译前把memory.x复制到输出目录,并追加--nmagic、-Tlink.x、-Tdefmt.x等链接参数,保证内存布局和 defmt 支持符合嵌入式需求。 - 依赖与特性:

Cargo.toml启用embassy-rp的rp235xa、time-driver、binary-info等特性,以及defmt、panic-probe,cargo 会按这些选项拉取并构建出能在 RP2350 上运行的固件。 - 环境变量:同一配置设定

DEFMT_LOG=debug,编译时写入日志等级,便于用 RTT 查看输出。

目标与运行器

.cargo/config.toml 设定交叉编译目标 thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf,runner 为 sudo picotool load -u -v -x -t elf,因此 cargo run 会编译后自动调用 picotool 把 ELF(可链接文件) 写入 Pico 2。

[target.'cfg(all(target_arch = "arm", target_os = "none"))']

#runner = "probe-rs run --chip RP2040"

#runner = "elf2uf2-rs -d"

runner = "sudo picotool load -u -v -x -t elf"

[build]

target = "thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf"

[env]

DEFMT_LOG = "debug"

构建脚本

运行 build.rs,同步 memory.x 并注入链接参数。

build.rs 保障了裸机固件的内存脚本可用、链接参数正确,且只在相关文件变化时重跑,减少不必要的构建成本。

该构建脚本一般是官方模板/社区随模板提供的,基本不用自己修改

依赖与特性

pico2-quick项目中的Cargo.toml,定义嵌入式异步运行时(Embassy)、Pico 2 芯片支持(embassy-rp 及特性)、调试与 panic 输出(defmt/ panic-probe),并通过 Cortex-M 运行时完成裸机启动。

[package]

name = "pico2-quick"

version = "0.2.0"

edition = "2024"

[dependencies]

# Embassy 的异步执行器,启用 Cortex-M 架构支持、线程化执行器和 defmt 日志集成。

embassy-executor = { version = "0.9", features = [

"arch-cortex-m",

"executor-thread",

"defmt",

] }

# panic 处理器,将崩溃信息通过 defmt 输出,便于 RTT 调试。

panic-probe = { version = "1.0", features = ["print-defmt"] }

# 异步定时器/计时工具。

embassy-time = { version = "0.5.0" }

# RP2 系列 HAL,启用 defmt 日志、时间驱动、临界区实现、RP235x A 版芯片支持,以及 picotool 用的 binary info 段。

embassy-rp = { version = "0.8.0", features = [

"defmt",

"time-driver",

"critical-section-impl",

"rp235xa",

"binary-info",

] }

# ARM Cortex-M 底层支持与运行时启动代码(向量表、reset handler)

cortex-m = { version = "0.7.6" }

cortex-m-rt = "0.7.5"

# 轻量日志框架及 RTT 后端,用于在调试器或 picotool 环境下输出日志。

defmt = "1.0.1"

defmt-rtt = "1.0"

烧录和调试

调用 runner:sudo picotool load -u -v -x -t elf <生成的ELF>,向 BOOTSEL 模式的 Pico 2 烧录固件。烧录完成后设备复位运行,LED 开始闪烁;需要调试时可通过 RTT 读取 defmt 日志。

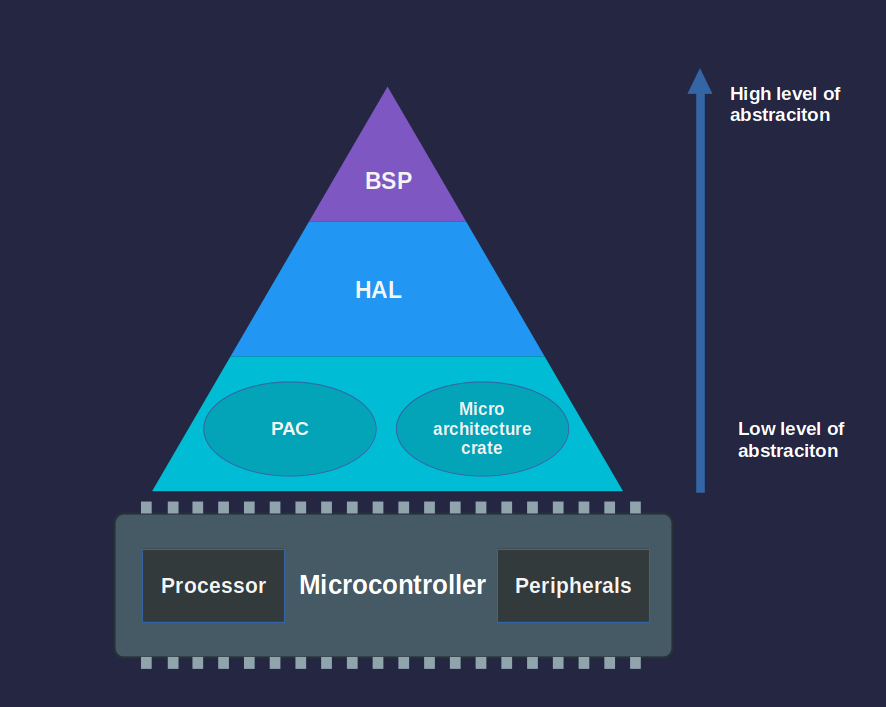

抽象层

在嵌入式 Rust 开发中,你经常会遇到 PAC、HAL 和 BSP 这样的术语。它们是与硬件交互的不同抽象层,每一层在灵活性与易用性之间做出不同的权衡。

下面从高到低介绍这些抽象层。

板级支持包(BSP)

BSP(在 Rust 中通常称为 Board Support Crate)是针对特定开发板的封装。它将 HAL 与板级配置结合,提供对板载组件(如 LED、按键、传感器)即插即用的接口,使开发者能更多关注应用逻辑而非底层细节。由于目前没有广泛使用的专门针对 Raspberry Pi Pico 2 的 BSP,本书不会采用该方式。

硬件抽象层(HAL)

HAL 位于 BSP 之下。如果你使用 Raspberry Pi Pico 或基于 ESP32 的板子,大多数场景会直接使用 HAL 层。HAL 通常以芯片为目标(例如 RP2350 或 ESP32),因此同一个 HAL 可以在多个使用相同微控制器的开发板间复用。针对 Raspberry Pi 家族微控制器,有社区维护的 rp-hal 仓库可供使用(https://github.com/rp-rs/rp-hal)。

HAL 构建在 PAC 之上,提供更简单的高层接口来操作外设。与直接操控寄存器不同,HAL 提供的方法与 trait 能更方便地完成定时器配置、串口初始化或 GPIO 控制等任务。

微控制器的 HAL 通常实现 embedded-hal trait,这是一套平台无关的外设接口(如 GPIO、SPI、I2C、UART),有助于编写可跨平台复用的驱动与库。

对于 Raspberry Pi:Embassy

Embassy 在抽象层次上与 HAL 同级,但它提供了一个带异步能力的运行时环境。Embassy(在本书中特指 embassy-rp)基于 HAL 层构建,提供异步执行器、定时器等抽象,简化编写并发嵌入式程序的复杂度。

针对 Raspberry Pi 微控制器(RP2040 / RP235x),有专门的 embassy-rp crate,构建于 rp-pac(Raspberry Pi Peripheral Access Crate)之上。

在本书中,我们会根据练习需要同时使用 rp-hal 与 embassy-rp。

注意:

HAL 之下的层通常不会被直接使用。大多数情况下通过 HAL 访问 PAC 即可。除非你所使用的芯片没有可用的 HAL,否则一般无需直接与低层交互。本书重点关注 HAL 层的使用。

外设访问包(PAC)

PAC 是最低级别的抽象,通常由厂商的 SVD(System View Description)文件生成,提供类型安全的寄存器访问接口。PAC 为直接操作硬件寄存器提供了结构化且更安全的方式(通常通过 svd2rust 工具生成)。

原始 MMIO

原始 MMIO(memory-mapped IO)指直接按地址读写硬件寄存器。这种方式类似传统 C 语言的寄存器操作,因其潜在风险在 Rust 中需要使用 unsafe 块。我们不会涉及这部分内容;在社区中这种做法并不常见。

项目模板 - 使用 cargo-generate

cargo-generate 是一个便捷工具,能通过使用已有的 Git 仓库作为模板,快速创建新的 Rust 项目。

更多信息请参见:https://github.com/cargo-generate/cargo-generate

前置要求

开始之前,请确保已安装以下工具:

- Rust

- cargo-generate(用于生成项目模板)

先安装 OpenSSL 开发包,因为 cargo-generate 依赖它:

sudo apt install libssl-dev

你可以通过下面的命令安装 cargo-generate:

cargo install cargo-generate

第 1 步:生成项目

运行下面命令,从模板生成项目:

cargo generate --git https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-template.git

执行后会提示你回答几个问题:

- Project name:为项目命名。

- HAL choice:可在

embassy或rp-hal之间选择。

第 2 步:默认的 LED 闪烁示例

默认生成的项目中包含一个简单的 LED 闪烁示例。项目结构可能类似:

src/main.rs:包含默认的闪烁逻辑。

Cargo.toml:包含为所选 HAL 添加的依赖项。

第 3 步:选择 HAL 并修改代码

项目生成后,你可以保留默认的 LED 示例,也可以将其删除并根据所选 HAL 替换为自己的代码。

移除不需要的代码

可以从 src/main.rs 中删掉示例的闪烁逻辑,并按需替换。根据项目需要修改 Cargo.toml 的依赖与项目结构。

运行程序

在深入其他示例之前,我们先覆盖在 Raspberry Pi Pico 2 上构建并运行任意程序的一般步骤。Pico 2 包含 ARM Cortex-M33 与 Hazard3 RISC-V 两类处理器,这里会给出两种架构的构建说明。

注意:下列命令应在你的项目目录中执行。若尚未创建项目,请先参阅“快速上手”或“Blink LED”章节。

在 ARM 模式下构建与运行

使用下面的命令为 Pico 2 的 ARM 模式(Cortex-M33)构建程序:

# 构建程序

cargo build --target=thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf

要将应用刷入 Pico 2,请按住 BOOTSEL 按钮,同时用 Micro USB 将设备连接到电脑。USB 插入后即可松开按钮。

# 运行程序

cargo run --target=thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf

说明: 示例工程中在 .cargo/config.toml 中配置了 runner,例如:

runner = "picotool load -u -v -x -t elf"。这意味着执行 cargo run 时会调用 picotool load 子命令来刷写程序。

在 RISC-V 模式下构建与运行

使用下面的命令为 Pico 2 的 RISC‑V 模式(Hazard3)构建程序。

注意:本书以 ARM 示例为主;部分示例在 RISC‑V 下可能需作调整。若想简化学习流程,建议优先按照 ARM 工作流进行操作。

# 构建程序

cargo build --target=riscv32imac-unknown-none-elf

按照前述 BOOTSEL 步骤把设备置于刷写模式,然后执行:

# 运行程序

cargo run --target=riscv32imac-unknown-none-elf

使用 Debug Probe

使用 Debug Probe 时,可以直接将程序刷入 Pico 2:

# cargo flash --chip RP2350

# cargo flash --chip RP2350 --release

cargo flash --release

若希望在刷写的同时查看实时输出,可使用:

# cargo embed --chip RP2350

# cargo embed --chip RP2350 --release

cargo embed --release

cargo-embed 是比 cargo-flash 更强大的工具,既能刷写程序,也能打开 RTT 终端与 GDB 服务。

帮助与故障排查

在完成练习时如果遇到任何 bug、错误或其他问题,可以参考以下方法进行排查和解决。

1. 与可运行代码对比

查看完整的代码示例,或克隆参考项目进行比对。仔细检查你的代码和 Cargo.toml 中的依赖版本。留意任何语法或逻辑错误。如果需要的 feature 未启用或存在 feature 不匹配,务必按练习所示启用正确的 feature。

如果发现版本不匹配,可以选择调整你的代码(查阅资料找到解决方案;这是学习和深入理解的好方法)以适配较新版本,或将依赖更新为教程中使用的版本。

2. 搜索或提交 GitHub Issue

访问 GitHub issues 页面,查看是否有人遇到相同问题: https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico-pico/issues?q=is%3Aissue

如果没有,你可以新建一个 issue,并清晰描述你的问题。

3. 向社区求助

Rust Embedded 社区在 Matrix 聊天中非常活跃。Matrix 是一个开放网络,用于安全、去中心化的通信。

以下是与本书涵盖主题相关的一些有用 Matrix 频道:

-

Embedded Devices Working Group

#rust-embedded:matrix.org

关于在嵌入式开发中使用 Rust 的通用讨论。 -

RP Series Development

#rp-rs:matrix.org

面向 Raspberry Pi RP 系列芯片的 Rust 开发与讨论。 -

Debugging with Probe-rs

#probe-rs:matrix.org

围绕 probe-rs 调试工具包的支持与讨论。 -

Embedded Graphics

#rust-embedded-graphics:matrix.org

使用embedded-graphics(面向嵌入式系统的绘图库)相关的交流。

你可以创建 Matrix 账号并加入这些频道,从经验丰富的开发者那里获得帮助。

更多社区聊天室可在 Awesome Embedded Rust - Community Chat Rooms 部分找到。

用于 Raspberry Pi Pico 2 的调试器(Debug Probe)

每次烧录新程序时都要按 BOOTSEL 按钮非常麻烦。像 ESP32 DevKit 这样的开发板大多能自动完成这一步,因为开发板可以在需要时将芯片重置到引导加载程序(bootloader)模式。Pico 2 本身不具备此功能,但通过使用调试器(debug probe),你不仅能获得同样的便利性,还能拥有更强的调试能力。

本章将解释为什么调试器很有用,并逐步指导你如何设置并使用它,在无需按 BOOTSEL 按钮的情况下对 Pico 2 进行烧录和调试。

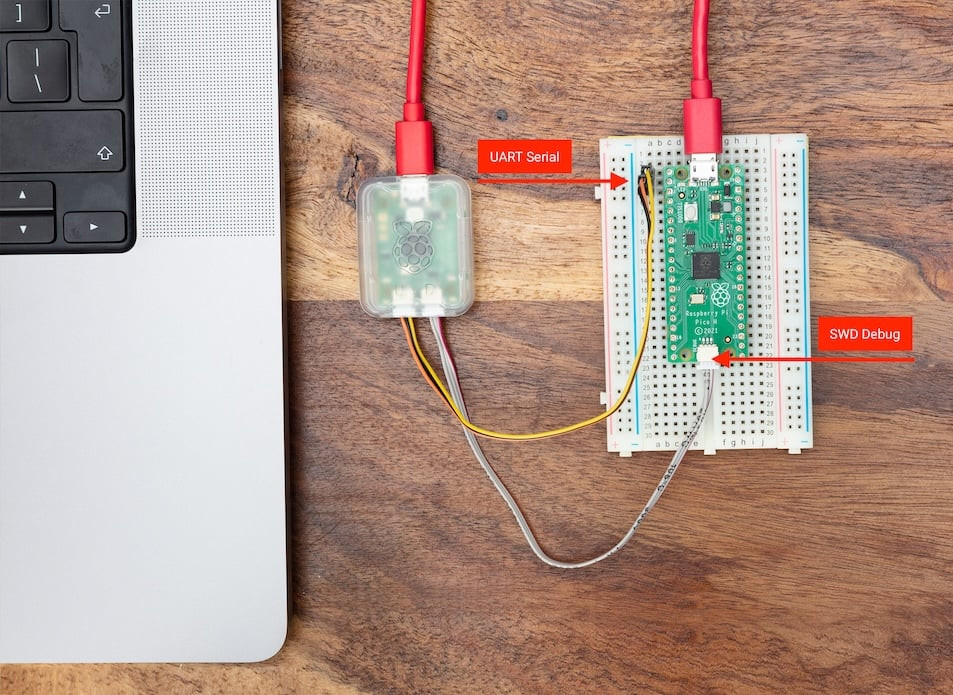

Raspberry Pi 调试器(Raspberry Pi Debug Probe)

Raspberry Pi 调试器是官方推荐用于 Pico 和 Pico 2 上 SWD 调试的工具。它是一个小型 USB 设备,充当 CMSIS-DAP 适配器。CMSIS-DAP 是一种开源调试器标准,允许你的电脑通过 SWD 协议与微控制器通信。

该调试器提供两大核心功能:

- SWD(Serial Wire Debug,串行线调试)接口:连接到 Pico 的调试引脚,用于烧录固件和进行实时调试。你可以设置断点、检查变量,就像在普通桌面应用程序中调试一样。

- UART 桥接器:提供 USB 转串口连接,让你能在电脑上查看控制台输出或与开发板通信。

这两项功能都通过同一根连接到电脑的 USB 线实现,因此无需额外的 UART 设备,使整体设置更加简洁。

焊接 SWD 引脚

在将调试器连接到 Pico 2 之前,你需要让 SWD 引脚 可被访问。这些引脚位于 Pico 板底部边缘,是一个独立于主 GPIO 引脚的小型 3 针调试排针。

一旦焊接好 SWD 引脚,你的 Pico 就可以连接调试器了。

准备调试器

你的调试器出厂时可能未预装最新固件,尤其是尚未包含对 Pico 2(RP2350 芯片)支持的版本。建议在开始使用前先更新固件。

Raspberry Pi 官方文档提供了清晰的调试器固件更新说明。请按照此处提供的步骤操作。

将 Pico 与调试器连接

调试器侧面有两个端口:

- D 端口:用于 SWD(调试)连接

- U 端口:用于 UART(串口)连接

SWD 连接(必需)

SWD 连接用于烧录固件和使用调试器。请使用随调试器附带的 JST 转杜邦线。

将调试器 D 端口的线缆按如下方式连接到 Pico 2 引脚:

| 调试器线缆颜色 | Pico 2 引脚 |

|---|---|

| 橙色 | SWCLK |

| 黑色 | GND |

| 黄色 | SWDIO |

连接前请确保 Pico 2 的 SWD 引脚已正确焊接。

UART 连接(可选)

如果你希望在电脑终端中查看串口输出(例如来自 Rust 的 println! 日志),UART 连接会非常有用。它与 SWD 连接相互独立。

将调试器 U 端口的线缆连接到 Pico 2 引脚:

| 调试器线缆颜色 | Pico 2 引脚 | 物理引脚编号 |

|---|---|---|

| 黄色 | GP0(Pico 的 TX) | 引脚 1 |

| 橙色 | GP1(Pico 的 RX) | 引脚 2 |

| 黑色 | GND | 引脚 3 |

虽然你可以使用任意配置为 UART 的 GPIO 引脚,但 GP0 和 GP1 是 Pico 默认的 UART0 引脚。

为 Pico 供电

调试器不会为 Pico 2 供电,仅提供 SWD 和 UART 信号。要为 Pico 2 供电,请将调试器通过 USB 连接到电脑,同时通过 Pico 2 自身的 USB 接口为其单独供电。只有两个设备都通电,调试才能正常工作。

最终设置

连接完成后:

- 将调试器通过 USB 插入电脑

- 确保 Pico 2 已通电

- 调试器上的红色 LED 应点亮,表示已通电

- 设置完成——从此无需再按 BOOTSEL 按钮

你现在可以直接通过开发环境对 Pico 2 进行烧录和调试,无需任何手动干预。

测试连接

要验证调试器与 Pico 2 是否正确连接,可以使用快速入门项目进行测试:

git clone https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-quick

cd pico2-quick

你不能像之前那样直接使用 cargo run,除非你修改了 config.toml 文件。因为该项目默认使用 picotool 作为运行器。你可以注释掉 picotool 运行器并启用 probe-rs 运行器,之后就能使用 cargo run 命令。

或者更简单的方式(推荐):直接使用 probe-rs 提供的以下命令,通过调试器烧录程序:

cargo flash

# 或

cargo flash --release

cargo embed

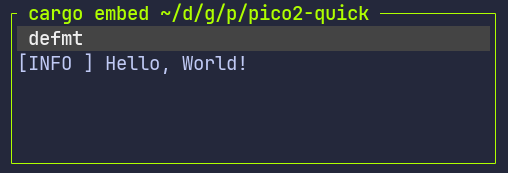

你可以使用 cargo embed 命令烧录程序并在终端中实时查看日志输出。快速入门项目已配置为通过 RTT 发送日志消息,因此无需额外配置即可直接使用。

cargo embed

# 或

cargo embed --release

如果你还不熟悉 RTT,我们稍后会详细解释。现在你只需运行上述命令,即可看到程序运行并打印日志。

如果一切正常,你应该会在系统终端中看到 “Hello, World!” 消息。

参考资料

实时传输(Real-Time Transfer, RTT)

在开发嵌入式系统时,你需要一种方式来观察程序内部的运行情况。在普通计算机上,你可以使用 println! 将消息打印到终端。但在微控制器上,并没有连接屏幕或终端。实时传输(Real-Time Transfer, RTT)通过允许你将调试信息和日志从微控制器发送到电脑,解决了这一问题。

什么是 RTT?

RTT 是一种通信方法,可让你的微控制器通过已用于烧录程序的调试器(debug probe)向电脑发送消息。

当你将 Raspberry Pi 调试器连接到 Pico 时,就建立了一个具备以下两种功能的连接:

- 向芯片烧录新程序

- 读写芯片内存

RTT 利用了这种内存访问能力。它在微控制器上创建特殊的内存缓冲区,调试器则读取这些缓冲区,并将消息显示在你的电脑上。这一切都在后台进行,不会影响程序的正常运行。

使用 Defmt 进行日志记录

Defmt(“deferred formatting”,即“延迟格式化”的缩写)是一个专为资源受限设备(如微控制器)设计的日志框架。在你的 Rust 嵌入式项目中,你将使用 defmt 来打印消息并调试程序。

Defmt 通过延迟格式化和字符串压缩实现高性能。所谓延迟格式化,是指格式化操作并非在记录日志的设备上完成,而是在另一台设备(如你的电脑)上进行。

你的 Pico 发送的是小型代码,而非完整的文本消息。你的电脑接收这些代码并将其还原为可读的文本。这种方式使固件体积更小,并避免了在微控制器上执行缓慢的字符串格式化操作。

你可以在项目中添加 defmt 依赖:

defmt = "1.0.1"

然后像这样使用它:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use defmt::{info, warn, error}; ... info!("Starting program"); warn!("You shall not pass!"); error!("Something went wrong!"); }

Defmt RTT

Defmt 本身并不知道如何将消息从 Pico 发送到电脑,它需要一个传输层。这就是 defmt-rtt 的作用所在。

defmt-rtt crate 将 defmt 与 RTT 连接起来,使你的日志消息能通过调试器传输到电脑。

你可以在项目中添加 defmt-rtt 依赖:

defmt-rtt = "1.0"

注意:要查看 RTT 和 defmt 日志,你需要使用

probe-rs工具(例如cargo embed命令)运行程序。这些工具会自动开启 RTT 会话,并在终端中显示日志。

然后在代码中引入它:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use defmt_rtt as _; }

这行代码建立了 defmt 与 RTT 之间的连接。你无需直接调用其中的任何函数,但必须导入该 crate 才能使其生效。

使用 Panic-Probe 显示 Panic 信息

当程序崩溃(panic)时,你希望看到具体出错的原因。panic-probe crate 可以让 panic 信息通过 defmt 和 RTT 显示出来。

你可以在项目中添加 panic-probe 依赖:

# print-defmt 特性:告诉 panic-probe 使用 defmt 输出信息。

panic-probe = { version = "1.0", features = ["print-defmt"] }

然后在代码中引入它:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use panic_probe as _; }

你可以手动触发一次 panic 来测试 panic 信息的显示效果。尝试在代码中加入以下内容:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { panic!("something went wrong"); }

闪烁外部 LED

从现在开始,我们将与 Pico 一起使用更多外部部件。在此之前,熟悉简单的电路以及如何将组件连接到 Pico 的引脚会有所帮助。在本章中,我们将从一个基本的东西开始:闪烁连接在电路板外的 LED。

硬件需求

- LED

- 电阻

- 跳线

组件概述

-

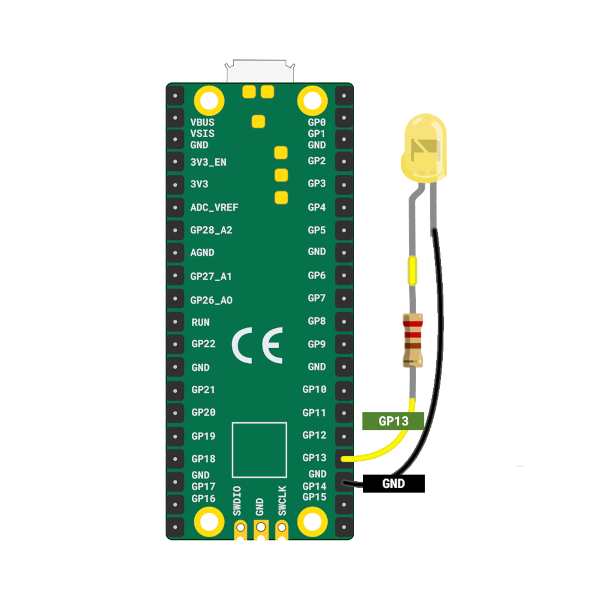

LED:发光二极管(LED)在电流通过时会发光。较长的引脚(阳极)连接到正极,较短的引脚(阴极)连接到地线。我们将阳极连接到 GP13(带电阻),阴极连接到 GND。

-

电阻:电阻限制电路中的电流,以保护 LED 等组件。其值以欧姆(Ω)计量。我们将使用 330 欧电阻来安全地为 LED 供电。

| Pico 引脚 | 导线 | 组件 |

|---|---|---|

| GPIO 13 |

|

电阻 |

| 电阻 |

|

LED 的阳极(长脚) |

| GND |

|

LED 的阴极(短脚) |

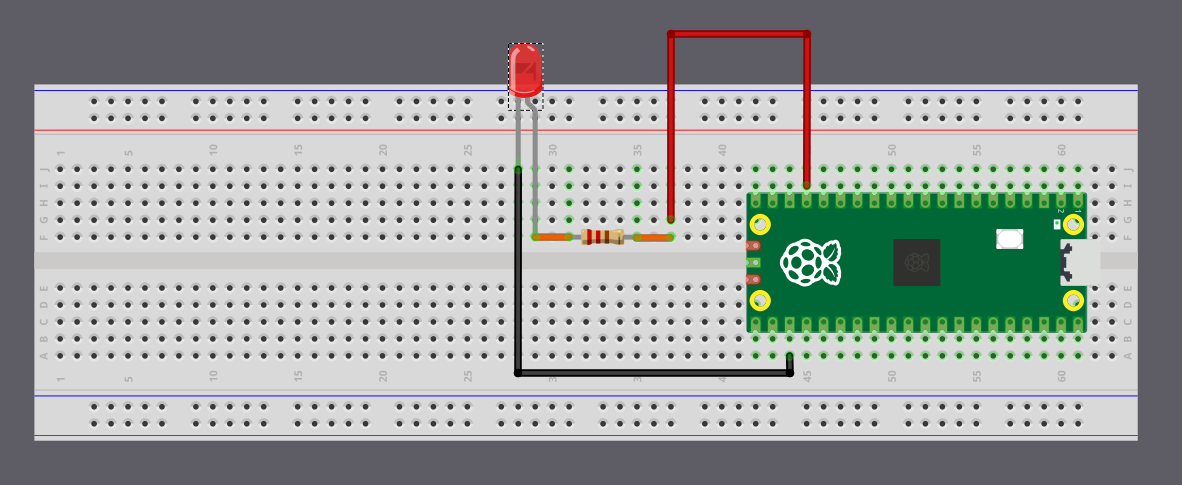

你可以使用跳线直接将 Pico 连接到 LED,或者可以在面包板上放置所有东西。如果你对硬件设置不确定,也可以参考 Raspberry Pi 指南。

注意:在 Pico 上,引脚标签在电路板的背面,在插入导线时可能会感到不便。我经常需要在想要使用通用输入输出(GPIO)引脚时检查引脚分配图。使用前面的 Raspberry Pi 标志作为参考点,并将其与引脚分配图相匹配以找到正确的引脚。引脚位置 2 和 39 也印在前面,可以作为额外的参考指南。

LED 闪烁 - 模拟

在这个模拟中,我将默认延迟设置为 5000 毫秒,以便动画更平缓,更容易跟踪。你可以将其降低到 500 毫秒左右,以看到 LED 闪烁得更快。当我们在 Pico 上运行实际代码时,我们将使用 500 毫秒的延迟。

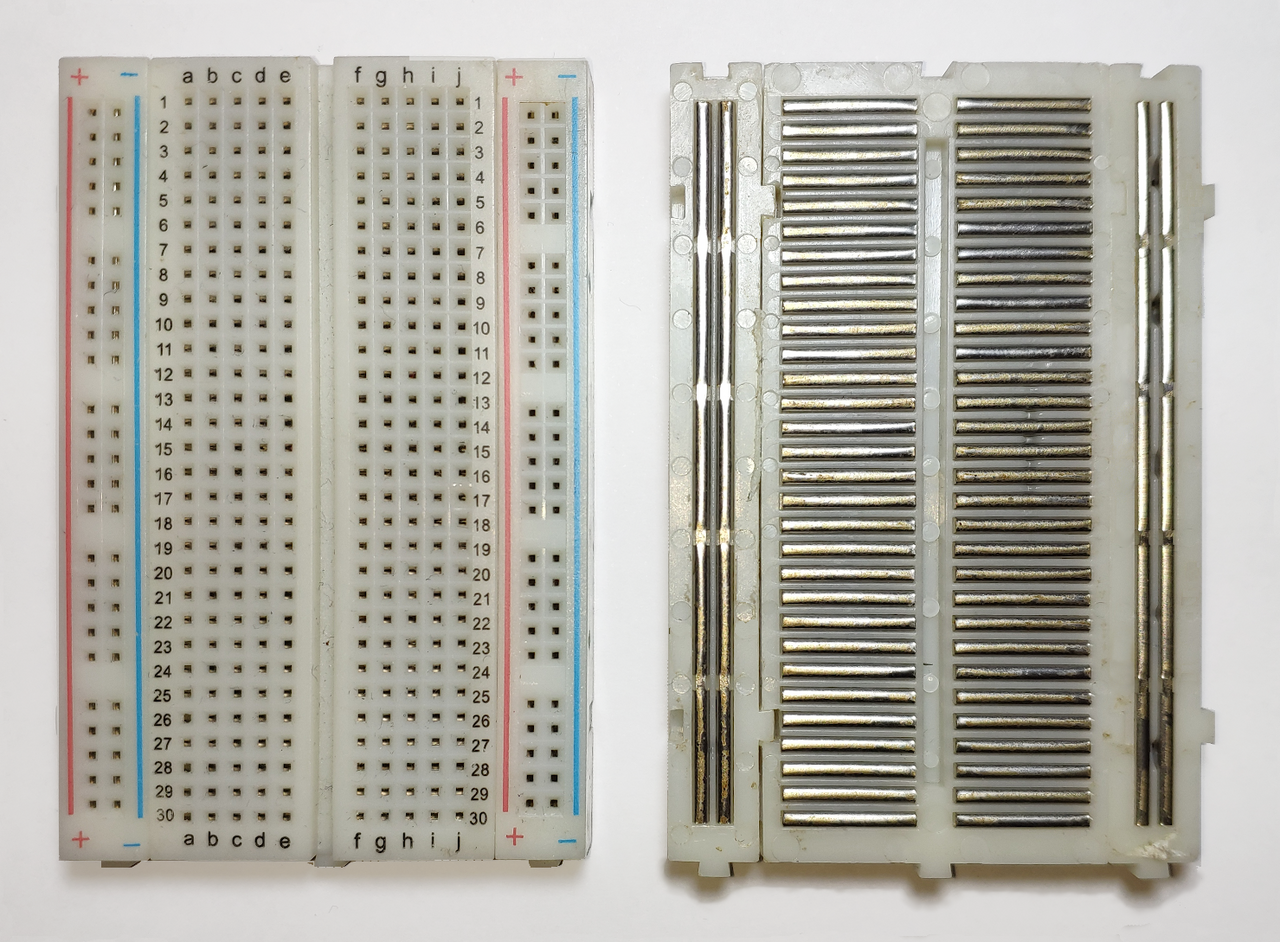

面包板

面包板(Breadboard)是一种无需焊接即可搭建电路的小型板子。它有许多孔洞,你可以在其中插入导线和电子元件。在板子内部,金属条连接了其中一些孔洞。这使得连接元件和完成电路变得非常简单。

这张图片展示了面包板内部的孔洞是如何连接的。

电源轨

两侧的长垂直线称为电源轨(Power rails)。人们通常将电源连接到标有"+"的轨道,将地线连接到标有"-"的轨道。轨道中的每个孔从上到下都是连接在一起的。

假设你想给多个元件供电。你只需要将电源(例如 3.3V 或 5V)连接到"+"轨道上的一个点。之后,你可以使用同一轨道上的任何其他孔来为你的元件供电。

中间区域

面包板的中间部分是你放置大部分元件的地方。这里的孔洞以小型水平行的方式连接。每一行有五个孔,它们在板子内部连接在一起。

如图所示,每一行都是独立的,标记为 a b c d e 的组与标记为 f g h i j 的组是分开的。中间的间隙将这两侧分隔开,因此连接不会从一侧跨越到另一侧。

以下是一些简单的例子:

- 如果你将一根导线插入 5a,另一根导线插入 5c,它们是连接的,因为它们在同一行。

- 如果你将一根导线插入 5a,另一根导线插入 5f,它们是不连接的,因为它们在间隙的不同侧。

- 如果你将一根导线插入 5a,另一根导线插入 6a,它们是不连接的,因为它们在不同的行。

使用嵌入式 Rust 在 Raspberry Pi Pico 上闪烁外部 LED

让我们从创建项目开始。我们将使用 cargo-generate 并使用我们为本书准备的模板。

在你的终端中,输入:

cargo generate --git https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-template.git --tag v0.3.1

你会被问到几个问题:

-

对于项目名称,你可以随意命名。我们将使用 external-led。

-

接下来,它会要求我们选择硬件抽象层(HAL)。我们应该选择 "Embassy"。

-

然后,它会询问我们是否要启用 defmt 日志记录。这仅在我们使用调试探针时有效,因此你可以根据你的设置进行选择。无论如何,在本次练习中我们不会编写任何日志。

导入

项目模板中已经包含了大部分所需的导入。对于本次练习,我们只需要从 gpio 中添加 Output 结构体和 Level 枚举:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use embassy_rp::gpio::{Level, Output}; }

在编写主代码时,你的编辑器通常会建议缺失的导入。如果没有建议或者你看到了错误,请检查完整代码部分并从那里添加缺失的导入。

主要逻辑

代码与快速开始示例几乎相同。唯一的区别是我们现在使用 GPIO 13 而不是 GPIO 25。GPIO 13 是我们连接 LED(通过电阻)的地方。

让我们将这些代码添加到主函数中:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut led = Output::new(p.PIN_13, Level::Low); loop { led.set_high(); // 打开 LED Timer::after_millis(500).await; led.set_low(); // 关闭 LED Timer::after_millis(500).await; } }

我们在这里使用 Output 结构体,因为我们想从 Pico 向 LED 发送信号。我们将 GPIO 13 设置为输出引脚,并使其初始状态为低电平(关闭)。

注意:如果你想从组件(如按钮或传感器)读取信号,则需要将 GPIO 引脚配置为输入(Input)。

然后我们在引脚上调用 set_high 和 set_low,并在它们之间设置延迟。这会在高电平和低电平之间切换引脚,从而打开和关闭 LED。

完整代码

这里是完整的代码供参考:

#![no_std] #![no_main] use embassy_executor::Spawner; use embassy_rp as hal; use embassy_rp::block::ImageDef; use embassy_rp::gpio::{Level, Output}; use embassy_time::Timer; // Panic处理程序(Panic Handler) use panic_probe as _; // Defmt 日志记录 use defmt_rtt as _; /// 告知引导 ROM(Boot ROM)关于我们的应用程序 #[unsafe(link_section = ".start_block")] #[used] pub static IMAGE_DEF: ImageDef = hal::block::ImageDef::secure_exe(); #[embassy_executor::main] async fn main(_spawner: Spawner) { let p = embassy_rp::init(Default::default()); let mut led = Output::new(p.PIN_13, Level::Low); loop { led.set_high(); // 打开 LED Timer::after_millis(500).await; led.set_low(); // 关闭 LED Timer::after_millis(500).await; } } // 用于 `picotool info` 的程序元数据。 // 这不是必需的,但建议保留这些最基本的条目。 #[unsafe(link_section = ".bi_entries")] #[used] pub static PICOTOOL_ENTRIES: [embassy_rp::binary_info::EntryAddr; 4] = [ embassy_rp::binary_info::rp_program_name!(c"external-led"), embassy_rp::binary_info::rp_program_description!(c"your program description"), embassy_rp::binary_info::rp_cargo_version!(), embassy_rp::binary_info::rp_program_build_attribute!(), ]; // 文件结束

克隆现有项目

你可以克隆我创建的项目并导航到 external-led 文件夹:

git clone https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-embassy-projects

cd pico2-embassy-projects/external-led

如何运行?

你可以参考 “运行程序” 章节

使用 rp-hal 的闪烁示例

在上一节中,我们使用了 Embassy。我们保持相同的电路和接线。对于这个示例,我们切换到 rp-hal 以展示这两种方法的样子。如果你想要异步支持,可以选择 Embassy;如果你更喜欢阻塞风格,可以选择 rp-hal。在本书中,我们将主要使用 Embassy。

我们将再次使用 cargo-generate 和相同的模板创建一个新项目。

在你的终端中,输入:

cargo generate --git https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-template.git --tag v0.3.1

当它要求你选择硬件抽象层(HAL)时,这次选择 "rp-hal"。

导入

模板已经包含了大部分导入。对于这个示例,我们需要从 embedded-hal 中添加 OutputPin 特性(trait):

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // 用于输出引脚的嵌入式 HAL 特性 use embedded_hal::digital::OutputPin; }

这个特性提供了我们将用来控制 LED 灯(LED)的 set_high() 和 set_low() 方法。

主要逻辑

如果你将此与 Embassy 版本进行比较,LED 切换的方式没有太大区别。主要区别在于延迟的工作方式。Embassy 使用 async 和 await,这允许程序在不阻塞的情况下暂停,并允许其他任务在后台运行。rp-hal 使用阻塞延迟,这会停止程序直到时间过去。

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut led_pin = pins.gpio13.into_push_pull_output(); loop { led_pin.set_high().unwrap(); timer.delay_ms(200); led_pin.set_low().unwrap(); timer.delay_ms(200); } }

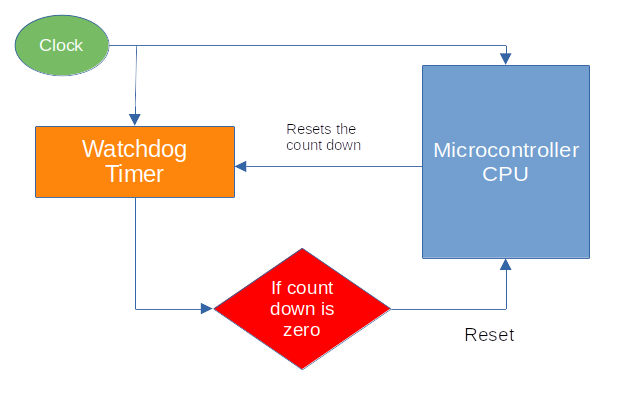

完整代码

#![no_std] #![no_main] use embedded_hal::delay::DelayNs; use hal::block::ImageDef; use rp235x_hal as hal; // 恐慌处理程序(Panic Handler) use panic_probe as _; // Defmt 日志记录 use defmt_rtt as _; // 用于输出引脚的嵌入式 HAL 特性 use embedded_hal::digital::OutputPin; /// 告知引导 ROM(Boot ROM)关于我们的应用程序 #[unsafe(link_section = ".start_block")] #[used] pub static IMAGE_DEF: ImageDef = hal::block::ImageDef::secure_exe(); /// Raspberry Pi Pico 2 开发板上的外部高速晶振为 12 MHz。 /// 如果你的开发板频率不同,请进行调整 const XTAL_FREQ_HZ: u32 = 12_000_000u32; #[hal::entry] fn main() -> ! { // 获取我们的单例对象 let mut pac = hal::pac::Peripherals::take().unwrap(); // 设置看门狗(watchdog)驱动程序 - 时钟设置代码需要它 let mut watchdog = hal::Watchdog::new(pac.WATCHDOG); // 配置时钟 // // 默认是生成 125 MHz 的系统时钟 let clocks = hal::clocks::init_clocks_and_plls( XTAL_FREQ_HZ, pac.XOSC, pac.CLOCKS, pac.PLL_SYS, pac.PLL_USB, &mut pac.RESETS, &mut watchdog, ) .ok() .unwrap(); // 单周期 I/O 块控制我们的通用输入输出(GPIO)引脚 let sio = hal::Sio::new(pac.SIO); // 根据它们在此特定开发板上的功能设置引脚 let pins = hal::gpio::Pins::new( pac.IO_BANK0, pac.PADS_BANK0, sio.gpio_bank0, &mut pac.RESETS, ); let mut timer = hal::Timer::new_timer0(pac.TIMER0, &mut pac.RESETS, &clocks); let mut led_pin = pins.gpio13.into_push_pull_output(); loop { led_pin.set_high().unwrap(); timer.delay_ms(200); led_pin.set_low().unwrap(); timer.delay_ms(200); } } // 用于 `picotool info` 的程序元数据。 // 这不是必需的,但建议保留这些最基本的条目。 #[unsafe(link_section = ".bi_entries")] #[used] pub static PICOTOOL_ENTRIES: [hal::binary_info::EntryAddr; 5] = [ hal::binary_info::rp_cargo_bin_name!(), hal::binary_info::rp_cargo_version!(), hal::binary_info::rp_program_description!(c"your program description"), hal::binary_info::rp_cargo_homepage_url!(), hal::binary_info::rp_program_build_attribute!(), ];

克隆现有项目

你可以克隆我创建的项目并导航到 external-led 文件夹:

git clone https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-rp-projects

cd pico2-rp-projects/external-led

从 std 到 no_std

我们已经成功烧录并运行了第一个程序,它产生了一个闪烁效果。然而,我们还没有详细探索代码或项目结构。在本节中,我们将从头开始重新创建同一个项目。我将沿途解释代码和配置的每一部分。你准备好接受挑战了吗?

注意:如果你觉得这一章内容太多,特别是如果你只是在做一个业余项目,请随意跳过它。你可以在构建一些有趣的项目并完成练习后再回来阅读。

创建一个新项目

我们将从创建一个标准的 Rust 二进制项目开始。使用以下命令:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { cargo new pico-from-scratch }

在这个阶段,项目将包含预期的常规文件。

├── Cargo.toml

└── src

└── main.rs

我们的目标是达到以下最终项目结构:

├── build.rs

├── .cargo

│ └── config.toml

├── Cargo.toml

├── memory.x

├── rp235x_riscv.x

├── src

│ └── main.rs

交叉编译

你可能已经了解交叉编译了。在本节中,我们将探讨它是如何工作的,以及处理像目标三元组(target triples)这样的东西意味着什么。简单来说,交叉编译就是为你正在使用的机器以外的机器构建程序。

你可以在一台计算机上编写代码,并制作在完全不同的计算机上运行的程序。例如,你可以在 Linux 上工作并为 Windows 构建 .exe 文件。你甚至可以针对像 RP2350、ESP32 或 STM32 这样的裸机微控制器(MCU)。

当我们开发目标是一个嵌入式设备时,便需要在PC机上编译出能在该嵌入式设备上运行的可执行文件,这里编译主机与目标运行主机不是同一个设备,那么该过程就称为交叉编译;

如C/C++文件要经过预处理(preprocessing)、编译(compilation)、汇编(assembly)和链接(linking)等4步才能变成可执行文件

编译=?编译

这里的“交叉编译”里的“编译”,通常是广义的 build:从源代码到目标平台可执行物/固件的整条流水线

- 狭义“编译”(compilation):把预处理后的 C/C++ 变成汇编(.s)或中间表示。

- 广义“编译/构建”(compile/build):把源代码一路变成目标产物(.elf/.exe/.uf2),包含链 接。 在日常交流中通常使用“编译”来统称,所以要结合语境。

核心概念

“交叉编译”不是某个单独步骤,而是:在 host 上运行的一套工具链(compiler/assembler/ linker 等),产出给 target 运行的二进制。从编译原理角度看:

- 前端(词法/语法/语义→IR)大体与平台无关;

- 后端(指令选择、寄存器分配、调用约定、目标文件格式、链接与运行时)强烈依赖 target

交叉编译的“交叉”,主要发生在后端与链接/运行时这部分。

更多的Target Triple可以参考: Target Triple不仅仅是字符串

简而言之(TL;DR)

在为 Pico 2 构建二进制文件时,我们必须使用 "thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf" 或 "riscv32imac-unknown-none-elf" 作为target。

cargo build --target thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf我们也可以在

.cargo/config.toml中配置target,这样就不需要每次都输入它了。

为你的主机系统构建

假设我们在 Linux 机器上。当你运行通常的构建命令时,Rust 会为你的当前主机平台编译代码,在这种情况下是 Linux:

cargo build

你可以使用 file 命令确认它刚刚生成了什么样的二进制文件:

file ./target/debug/pico-from-scratch

这将给出如下输出。这告诉你它是一个 64 位 ELF 二进制文件,动态链接,并且是为 Linux 构建的。

./target/debug/pico-from-scratch: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, Build...

为 Windows 交叉编译

现在假设你想在不离开 Linux 机器的情况下为 Windows 构建二进制文件。这就是交叉编译发挥作用的地方。

首先,你需要告诉 Rust 目标平台。你只需要做一次:

rustup target add x86_64-pc-windows-gnu

这添加了对使用 GNU 工具链(MinGW)生成 64 位 Windows 二进制文件的支持。

现在再次构建你的项目,这次指定目标:

cargo build --target x86_64-pc-windows-gnu

就是这样。Rust 现在将创建一个 Windows .exe 二进制文件,即使你仍然在 Linux 上。输出的二进制文件将位于 target/x86_64-pc-windows-gnu/debug/pico-from-scratch.exe

你可以像这样检查文件类型:

file target/x86_64-pc-windows-gnu/debug/pico-from-scratch.exe

它会给你这样的输出,一个用于 Windows 的 64 位 PE32+ 文件格式文件。

target/x86_64-pc-windows-gnu/debug/pico-from-scratch.exe: PE32+ executable (console) x86-64, for MS Windows

什么是目标三元组?

那么 x86_64-pc-windows-gnu 这个字符串到底是什么?

这就是我们所说的目标三元组(target triple),它准确地告诉编译器你想要什么样的输出。它通常遵循这种格式:

`<architecture>-<vendor>-<os>-<abi>`

但这种模式并不总是一致的。有时 ABI 部分不会出现。在其他情况下,甚至供应商(vendor)或者供应商和 ABI 都可能缺失。结构可能会变得混乱,并且有很多例外。如果你想深入了解所有的怪癖和边缘情况,请查看参考资料中链接的文章 "What the Hell Is a Target Triple?"。

让我们分解一下这个目标三元组的实际含义:

-

架构(Architecture)(x86_64):这只是意味着 64 位 x86,这是大多数现代 PC 使用的 CPU 类型。它也被称为 AMD64 或 x64。

-

供应商(Vendor)(pc):这基本上是一个占位符。在大多数情况下它不是很重要。如果是针对 mac os,供应商名称将是 "apple"。

-

操作系统(OS)(windows):这告诉 Rust 我们想要构建在 Windows 上运行的东西。

-

二进制接口(ABI)(gnu):这部分告诉 Rust 使用 GNU 工具链来构建二进制文件。

参考资料

为微控制器编译

现在让我们谈谈嵌入式系统。当涉及到为微控制器编译 Rust 代码时,情况与普通桌面系统略有不同。微控制器通常不运行像 Linux 或 Windows 这样的完整操作系统。相反,它们在一个最小的环境中运行,通常根本没有操作系统。这被称为裸机(bare-metal)环境。

Rust 通过其 no_std 模式支持这种设置。在普通的 Rust 程序中,标准库(std)处理文件系统、线程、堆分配和 I/O 等事务。但在裸机微控制器上,这些都不存在。因此,我们不使用 std,而是使用一个小得多的 core 库,它只提供基本的构建块。

Pico 2 的目标三元组

Raspberry Pi Pico 2(RP2350 芯片),正如你已经知道的那样,它是独特的;它包含可选择的 ARM Cortex-M33 和 Hazard3 RISC-V 核心。你可以选择使用哪种处理器架构。

ARM Cortex-M33 目标

对于 ARM 模式,我们必须使用目标 [thumbv8m.main-none-eabi](https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/rustc/platform-support/thumbv8m.main-none-eabi.html):

让我们分解一下:

- 架构(Architecture)(thumbv8m.main):Cortex-M33 使用用于 ARMv8-M 架构的 ARM Thumb-2 指令集。

- 供应商(Vendor)(none):没有特定的供应商指定。

- 操作系统(OS)(none):没有操作系统 - 它是裸机的。

- 二进制接口(ABI)(eabi):嵌入式应用二进制接口(Embedded Application Binary Interface),嵌入式 ARM 系统的标准调用约定。

要安装并使用此目标:

rustup target add thumbv8m.main-none-eabi

cargo build --target thumbv8m.main-none-eabi

RISC-V Hazard3 目标

对于 RISC-V 模式,使用目标: riscv32imac-unknown-none-elf

让我们分解一下:

- 架构(Architecture)(riscv32imac):具有 I(整数)、M(乘法/除法)、A(原子)和 C(压缩)指令集的 32 位 RISC-V。

- 供应商(Vendor)(unknown):没有特定的供应商。

- 操作系统(OS)(none):没有操作系统 - 它是裸机的。

- 格式(Format)(elf):ELF(可执行和可链接格式),嵌入式系统中常用的对象文件格式。

要安装并使用此目标:

rustup target add riscv32imac-unknown-none-elf

cargo build --target riscv32imac-unknown-none-elf

在我们的练习中,我们将主要使用 ARM 模式。像 panic-probe 这样的一些 crate 在 RISC-V 模式下无法工作。

Cargo 配置

在快速开始中,你可能已经注意到我们在运行 cargo 命令时从未手动传递 --target 标志。那么它是如何知道要为哪个目标构建的呢?这是因为目标已经在 .cargo/config.toml 文件中配置好了。

这个文件允许你存储与 cargo 相关的设置,包括默认使用哪个目标。要为 ARM 模式下的 Pico 2 设置它,请在你的项目根目录中创建一个 .cargo 文件夹,并添加一个包含以下内容的 config.toml 文件:

[build]

target = "thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf"

现在你不必每次都传递 --target。Cargo 将自动使用此设置。

no_std

Rust 有两个主要的 crate:std 和 core。

-

stdcrate 是标准库。它为你提供了诸如堆分配、文件系统访问、线程和println!等功能。 -

corecrate 是一个最小子集。它仅包含最基本的 Rust 功能,例如基本类型(Option、Result等)、trait 以及少数其他操作。它不依赖于操作系统或运行时。

当你尝试在这个阶段构建项目时,你会得到一堆错误。如下所示:

error[E0463]: can't find crate for `std`

|

= note: the `thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf` target may not support the standard library

= note: `std` is required by `pico_from_scratch` because it does not declare `#![no_std]`

error: cannot find macro `println` in this scope

--> src/main.rs:2:5

|

2 | println!("Hello, world!");

| ^^^^^^^

error: `#[panic_handler]` function required, but not found

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0463`.

error: could not compile `pico-from-scratch` (bin "pico-from-scratch") due to 3 previous errors

这里有很多错误。让我们逐一修复。第一个错误说目标平台可能不支持标准库。这是真的。我们已经知道了。问题在于,我们没有告诉 Rust 我们不想使用 std。这就是 no_std 属性发挥作用的地方。

#![no_std]

#![no_std] 属性禁用了标准库(std)的使用。这对于嵌入式系统开发通常是必要的,因为这种环境通常缺乏标准库所假设可用的许多资源(如操作系统、文件系统或堆分配)。

在你的 src/main.rs 文件顶部,添加这行代码:

#![no_std]

就是这样。现在 Rust 知道这个项目将只会使用 core 库,而不是 std。

Println

println! 宏来自 std crate。由于我们在项目中不使用 std,我们也不能使用 println!。让我们继续并将其从代码中移除。

现在代码应该像这样:

#![no_std] fn main() { }

通过这个修复,我们已经处理了两个错误并减少了错误列表。还有一个问题依然存在,我们将在下一节中修复它。

参考资源:

Panic 处理器

此时,当你尝试构建项目时,你会得到这个错误:

error: `#[panic_handler]` function required, but not found

当 Rust 程序发生 panic(恐慌)时,通常由标准库提供的内置 panic 处理器来处理。但在上一步中,我们添加了 #![no_std],这告诉 Rust 不要使用标准库。所以现在,默认情况下没有可用的 panic 处理器。

在 no_std 环境中,你需要定义自己的 panic 行为,因为当出错时没有操作系统或运行时来接管。

我们可以通过添加自己的 panic 处理器来修复这个问题。只需创建一个带有 #[panic_handler] 属性的函数。该函数必须接受一个 PanicInfo 的引用,并且其返回类型必须是 !,这意味着该函数永不返回。

将此添加到你的 src/main.rs:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[panic_handler] fn panic(_: &core::panic::PanicInfo) -> ! { loop {} } }

Panic Crates

有一些现成的 crate 为 no_std 项目提供了 panic 处理器函数。一个简单且常用的 crate 是 "panic_halt",它在发生 panic 时只是停止执行。

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use panic_halt as _; }

这行代码从该 crate 中引入了 panic 处理器。现在,如果发生 panic,程序就会停止并停留在无限循环中。

实际上,panic_halt crate 的代码实现了一个简单的 panic 处理器,如下所示:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use core::panic::PanicInfo; use core::sync::atomic::{self, Ordering}; #[inline(never)] #[panic_handler] fn panic(_info: &PanicInfo) -> ! { loop { atomic::compiler_fence(Ordering::SeqCst); } } }

你可以使用像这样的外部 crate,也可以手动编写你自己的 panic 处理器函数。这取决于你。

译者注:panic-probe 的深度机制

对于使用 Embassy 或 probe-rs 工具链的开发者,推荐使用 panic-probe 替代 panic-halt。

panic-probe的源码在:https://github.com/knurling-rs/defmt/blob/main/firmware/panic-probe/src/lib.rs

差异

panic-halt 通过无限循环停止程序:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { loop { atomic::compiler_fence(Ordering::SeqCst); } }

panic-probe 通过硬件陷阱触发调试器:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { cortex_m::asm::udf(); // 执行未定义指令 }

panic-probe的原理

panic-probe 的执行流程:

- 禁用中断:

cortex_m::interrupt::disable()确保 panic 处理的原子性 - 递归防护:使用

AtomicBool避免嵌套 panic 时的无限递归 - 可选日志输出:

print-defmtfeature:通过 defmt 输出格式化消息print-rttfeature:通过 RTT 实时传输错误信息

- 禁用 UsageFault:清除 SHCSR 寄存器的第 18 位(仅 ARMv7-M 及以上)

- 触发 UDF 指令:执行

0xDEFF(UDF #255)指令

UDF 指令的魔法

udf #255 ; 未定义指令

当 CPU 执行 UDF 后:

- 触发 HardFault 异常(最高优先级)

- 自动保存寄存器上下文到栈:

R0-R3, R12, LR, PC, xPSR probe-rs识别特定的 UDF 编码,捕获断点- 通过 DWARF 调试信息回溯完整调用栈

使用方式

# Cargo.toml

[dependencies]

panic-probe = { version = "1.0", features = ["print-defmt"] }

defmt = "1.0.1"

defmt-rtt = "1.0"

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // src/main.rs use {defmt_rtt as _, panic_probe as _}; }

当程序 panic 时,probe-rs 会自动输出:

ERROR panicked at src/main.rs:42:17

index out of bounds: the len is 3 but the index is 5

Stack backtrace:

0: rust_begin_unwind (panic-probe)

1: core::panicking::panic_fmt

2: your_app::buggy_function

参考资源:

no_main

当你尝试在这个阶段构建时,你会得到一个错误,说 main 函数需要标准库。那么现在怎么办?程序到底是从哪里开始的?

在嵌入式系统中,我们不使用依赖于标准库的常规 "fn main"。相反,只要告诉 Rust 我们会提供我们自己的入口点。为此,我们使用 no_main 属性。

#![no_main] 属性用于指示程序将不使用标准入口点(fn main)。

在你的 src/main.rs 文件顶部,添加这行代码:

#![no_main]

声明入口点

既然我们已经选择不使用默认入口点,我们需要告诉 Rust 从哪个函数开始。嵌入式 Rust 生态系统中的每个硬件抽象层(HAL)crate 都提供了一个特殊的属性宏(proc macro),允许我们标记入口点。这个宏会初始化并设置微控制器所需的一切。

如果我们使用 rp-hal,我们可以对 RP2350 芯片使用 rp235x_hal::entry。但是,我们将使用 Embassy(embassy-rp crate)。Embassy 提供了 embassy_executor::main 宏,它为任务设置异步运行时并调用我们的 main 函数。

Embassy Executor 是更为嵌入式使用设计的 async/await 执行器,并支持中断和计时器功能。你可以阅读官方的 Embassy 书籍 来深入了解 Embassy 的工作原理。

Cortex-m Run Time

如果你追踪 embassy_executor::main 宏,你会看到它根据架构使用另一个宏。由于 Pico 2 是 Cortex-M 架构,它使用 cortex_m_rt::entry。这来自 cortex_m_rt crate,它为 Cortex-M 微控制器提供启动代码和最小运行时。

如果你在 quick-start 项目中运行 cargo expand,你可以看到宏是如何展开的以及完整的执行流程。如果你深入研究,程序是从 __cortex_m_rt_main_trampoline 函数开始的。这个函数调用 __cortex_m_rt_main,后者设置 Embassy 执行器并运行我们的 main 函数。

注意使用 cargo expand 请先执行cargo install cargo-expand

这个cargo-expand是用来展开 Rust 中的宏定义(macro expansion)和 #[derive] 注解的扩展效果。

为了使用这个功能,我们需要将 cortex-m 和 cortex-m-rt crate 添加到我们的项目中。更新 Cargo.toml 文件:

cortex-m = { version = "0.7.6" }

cortex-m-rt = "0.7.5"

现在,我们可以添加 embassy-executor crate:

embassy-executor = { version = "0.9", features = [

"arch-cortex-m",

"executor-thread",

] }

然后,在你的 main.rs 中,像这样设置入口点:

use embassy_executor::Spawner; #[embassy_executor::main] async fn main(_spawner: Spawner) {}

我们已经更改了函数签名。该函数必须接受一个 Spawner 作为参数以满足 Embassy 的要求,并且该函数现在被标记为 async。

我们到了吗?

万岁!现在尝试构建项目 - 它应该能成功编译。

你可以使用 file 命令检查生成的二进制文件:

file target/thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf/debug/pico-from-scratch

它会显示类似这样的内容:

target/thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf/debug/pico-from-scratch: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, ARM, EABI5 version 1 (GNU/Linux), statically linked, with debug_info, not stripped

如你所见,该二进制文件是为 32-bit ARM 构建的。这意味着我们 Pico 的基础设置正在工作。

但是我们到了吗?还没完全到。我们已经完成了这一阶段的一半工作 - 我们现在有了一个准备好在 Pico 上运行的有效二进制文件,但在我们可以在真实硬件上运行它之前,还有更多工作要做。

参考资源:

适用于 Raspberry Pi Pico 的 Embassy

我们在介绍章节中已经介绍了硬件抽象层(HAL)的概念。对于 Pico,我们将使用 Embassy RP HAL。Embassy RP HAL 旨在支持 Raspberry Pi RP2040 以及 RP235x 微控制器。

该 HAL 支持阻塞和异步外设 API。使用异步 API 更好,因为 HAL 会自动处理在低功耗模式下等待外设完成操作的时间,并管理中断,让你能专注于核心功能。

让我们将 embassy-rp crate 添加到我们的项目中。

embassy-rp = { version = "0.8.0", features = [

"rp235xa",

] }

我们启用了 rp235xa 特性,因为我们的芯片是 RP2350。如果我们使用旧款 Pico,则应改为启用 rp2040 特性。

初始化 embassy-rp HAL

让我们初始化 HAL。如果需要,我们可以将自定义配置传递给初始化函数。目前的配置允许我们修改时钟设置,但现在我们将坚持使用默认值:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let peripherals = embassy_rp::init(Default::default()); }

这会给我们提供所需的外设单例。请记住,我们应该只在启动时调用这一次;再次调用会导致 panic。

计时器

我们将通过让板载 LED 闪烁来复刻快速开始示例。为了制作闪烁效果,我们需要一个计时器在 LED 开关之间添加延迟。如果没有延迟,闪烁速度会太快导致肉眼无法察觉。

为了处理计时,我们将使用 "embassy-time" crate,它提供了必要的计时功能:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { embassy-time = { version = "0.5.0" } }

我们还需要在 embassy-rp crate 中启用 time-driver 特性。这将把 TIMER 外设配置为 embassy-time 的全局时间驱动,以 1MHz 的频率运行:

embassy-rp = { version = "0.8.0", features = [

"rp235xa",

"time-driver",

"critical-section-impl",

] }

我们几乎已经添加了所有核心 crate。现在让我们编写实现闪烁效果的代码。

Raspberry Pi Pico 2 板载 LED 闪烁

当你开始进行嵌入式编程时,通用输入输出(GPIO)是你首先会接触的外设。“通用输入输出”顾名思义:我们可以将其用于输入和输出。作为输出,Pico 可以发送信号来控制 LED 等组件。作为输入,按钮等组件可以向 Pico 发送信号。

在本练习中,我们将通过向板载 LED 发送信号来控制它。如果你查看 Pico 2 数据手册的第 8 页,你会看到板载 LED 连接在 GPIO 引脚 25 上。

我们将 GPIO 引脚 25 配置为输出引脚,并将其初始状态设置为低电平(关闭):

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut led = Output::new(peripherals.PIN_25, Level::Low); }

大多数代码编辑器(如 VS Code)都有快捷键可以自动为你添加导入。如果你的编辑器没有此功能或者你遇到了问题,可以手动添加这些导入:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use embassy_rp::gpio::{Level, Output}; }

闪烁逻辑

现在,我们将创建一个简单的循环让 LED 闪烁。首先,我们通过在 GPIO 实例上调用 set_high() 函数来打开 LED。然后我们使用 Timer 添加一个短暂的延迟。接下来,我们使用 set_low() 关闭 LED。然后我们再添加一个延迟。这就产生了闪烁效果。

让我们将 Timer 导入到我们的项目中:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use embassy_time::Timer; }

这是闪烁循环代码:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { loop { led.set_high(); Timer::after_millis(250).await; led.set_low(); Timer::after_millis(250).await; } }

将 Rust 固件烧录到 Raspberry Pi Pico 2

在构建我们的程序后,我们将得到一个可以烧录的 ELF 二进制文件。

对于调试构建(cargo build),你可以在这里找到文件:

./target/thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf/debug/pico-from-scratch

对于发布构建(cargo build --release),你可以在这里找到它:

./target/thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf/release/pico-from-scratch

要将我们的程序加载到 Pico 上,我们将使用一个名为 Picotool 的工具。这是烧录我们程序的命令:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { picotool load -u -v -x -t elf ./target/thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf/debug/pico-from-scratch }

以下是每个标志的作用:

-u用于更新模式(仅写入更改的内容)-v用于验证所有内容是否正确写入-x用于在加载后立即运行程序-t elf告诉picotool我们正在使用 ELF 文件

cargo run 命令

每次都输入那个长命令很令人厌烦。让我们通过更新 .cargo/config.toml 文件来简化它。我们可以将 Cargo 配置为在运行 cargo run 时自动使用 picotool:

[target.thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf]

runner = "picotool load -u -v -x -t elf"

现在,你只需要输入:

cargo run --release

#or

cargo run

你的程序就会被烧录并在 Pico 上执行。

但在此刻,它实际上还不能烧录。我们遗漏了一个重要的步骤。

链接脚本

程序现在可以成功编译。然而,当你尝试将其烧录到 Pico 上时,你可能会遇到如下错误:

ERROR: File to load contained an invalid memory range 0x00010000-0x000100aa

将我们的项目与快速开始项目进行对比

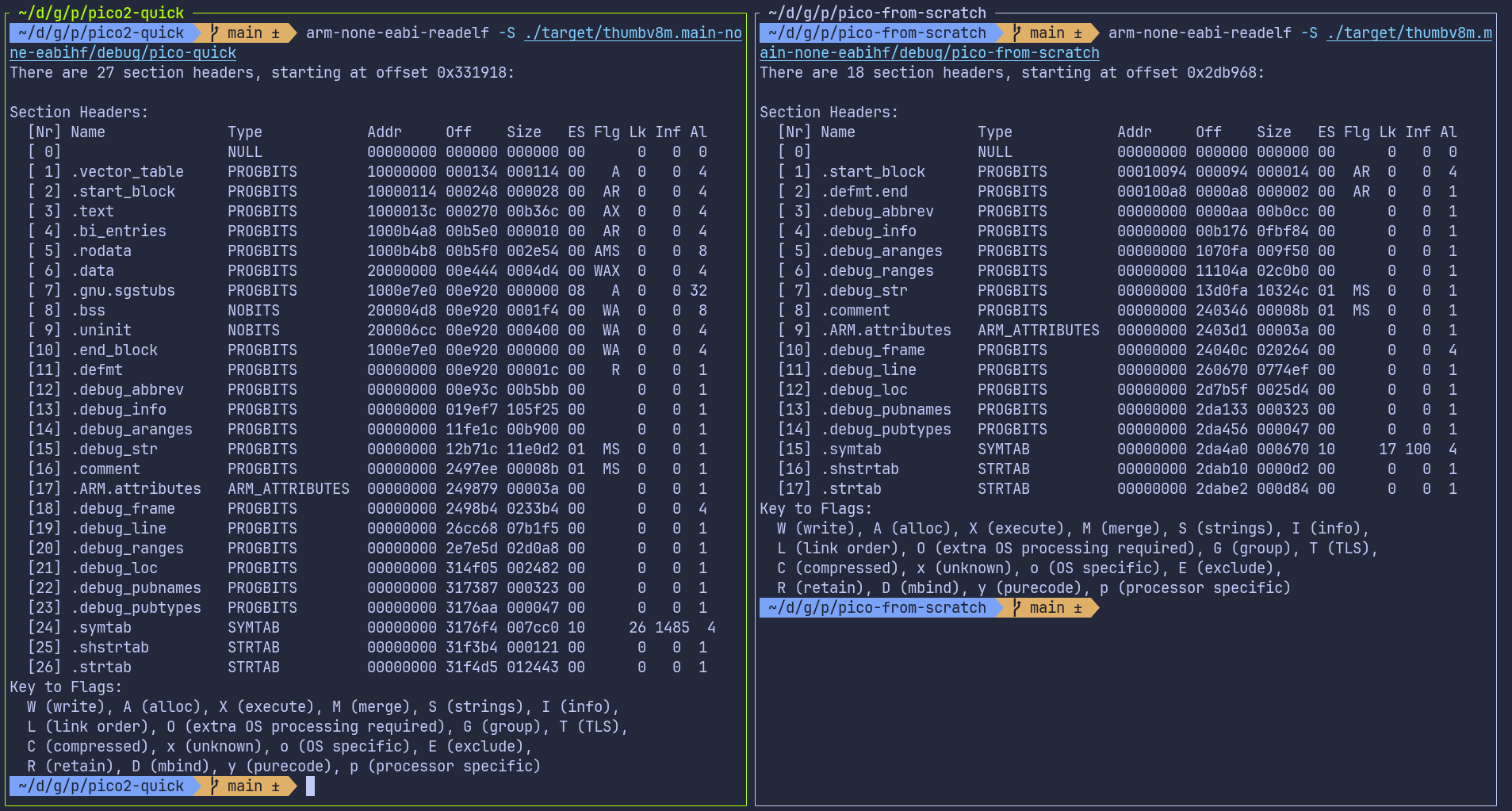

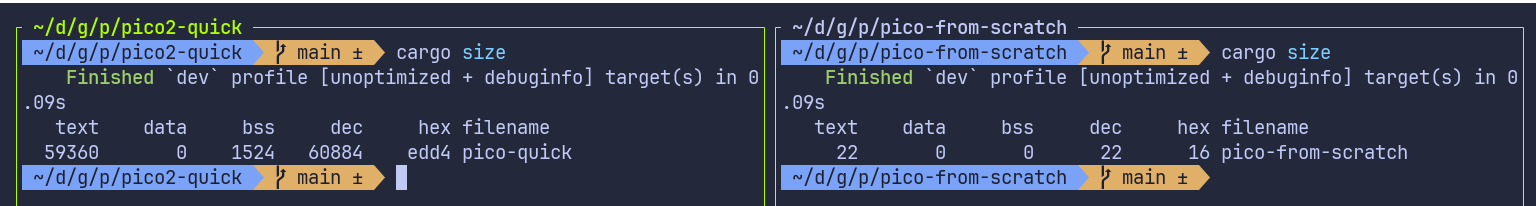

为了理解为什么烧录会失败,让我们使用 arm-none-eabi-readelf 工具检查编译后的程序。这个工具展示了编译器和链接器是如何在内存中组织程序的。

我取出了 quick-start 项目的二进制文件,并将其与我们项目当前生成的二进制文件进行了比较。

你不需要理解输出中的每一个细节。重要的是要注意到这两个二进制文件看起来非常不同,尽管我们的 Rust 代码几乎是一样的。

最大的区别在于我们的项目缺失了一些重要的段(section),如 .text、.rodata、.data 和 .bss。这些段通常由链接器创建:

- .text : 实际的程序指令(代码)存放于此

- .rodata : 只读数据,例如常量值

- .data : 已初始化的全局或静态变量

- .bss : 未初始化的全局或静态变量

你还可以通过 cargo-binutils 工具集提供的 cargo size 命令来比较它们。

链接器(Linker):

这通常由所谓的链接器来处理。链接器的作用是将我们程序的所有部分(如编译后的代码、库代码、启动代码和数据)组合成一个设备实际上可以运行的最终可执行文件。它还决定了程序的每个部分应该放置在内存中的什么位置,例如代码放在哪里,全局变量放在哪里。

然而,链接器不会自动知道 RP2350 的内存布局。我们必须告诉它 Flash 和 RAM 是如何排列的。这是通过链接脚本完成的。如果链接脚本缺失或不正确,链接器就不会将我们的代码放置在正确的内存区域中,从而导致我们看到的烧录错误。

链接脚本

我们不打算自己编写链接脚本。cortex-m-rt crate 已经提供了主链接脚本(link.x),但它只了解 Cortex-M 核心。它对我们使用的具体微控制器一无所知。每个微控制器都有自己的 Flash 大小、RAM 大小和内存布局,cortex-m-rt 无法猜测这些值。

因此,cortex-m-rt 期望用户或板级支持 crate 提供一个名为 memory.x 的小型链接脚本。该文件描述了目标设备的内存布局。

在 memory.x 中,我们必须定义设备拥有的内存区域。至少,我们需要两个区域:一个名为 FLASH,另一个名为 RAM。程序的 .text 和 .rodata 段会被放置在 FLASH 区域。.bss 和 .data 段以及堆(heap)会被放置在 RAM 区域。

对于 RP2350,数据手册(第 2.2 章,Address map)通过指出 Flash 起始地址为 0x10000000,SRAM 起始地址为 0x20000000。所以我们的 memory.x 文件看起来会像这样:

MEMORY {

FLASH : ORIGIN = 0x10000000, LENGTH = 2048K

RAM : ORIGIN = 0x20000000, LENGTH = 512K

SRAM4 : ORIGIN = 0x20080000, LENGTH = 4K

SRAM5 : ORIGIN = 0x20081000, LENGTH = 4K

...

...

}

...

...

RP2350 在 memory.x 中还需要一些额外的设置。我们不需要手动编写这些内容。相反,我们将使用 embassy-rp 示例仓库中提供的文件。你可以从这里下载它,并将其放置在你的项目根目录下。

链接器的代码生成选项

仅仅将 memory.x 文件放在项目文件夹中是不够的。我们还需要确保链接器实际上使用了 cortex-m-rt 提供的链接脚本。

为了解决这个问题,我们要告诉 Cargo 将链接脚本(link.x)传递给链接器。我们可以通过多种方式将参数传递给 Rust。我们可以使用 .cargo/config.toml 或构建脚本(build.rs)文件等方法。在快速开始中,我们使用的是 build.rs。所以这里我们将使用 .cargo/config.toml 方式。在该文件中,使用以下内容更新目标(target)部分:

[target.thumbv8m.main-none-eabihf]

runner = "picotool load -u -v -x -t elf" # 我们已经添加了这个

rustflags = ["-C", "link-arg=-Tlink.x"] # 这是新增的一行

运行 Pico

一切设置就绪后,你现在可以将程序烧录到 Pico 上了:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { cargo run --release }

呼……我们将一个普通的 Rust 项目变成了一个用于 Pico 的 no_std 固件。终于,我们可以看到 LED 闪烁了。

参考资源

脉宽调制(PWM)

在本节中,我们将探索什么是 PWM 以及为什么我们需要它。

数字与模拟

为了理解 PWM,我们首先需要理解什么是数字信号和模拟信号。

数字信号

数字信号只有两种状态:HIGH(高电平)或 LOW(低电平)。在微控制器(MCU)中,HIGH 通常意味着全电压(5V 或 3.3V),而 LOW 意味着 0V。两者之间没有任何值。把它想象成一个电灯开关,只能是完全“开”或完全“关”。

当你使用微控制器上的数字引脚时,你只能输出这两个值。如果你向引脚写入 HIGH,它输出 3.3V。如果你写入 LOW,它输出 0V。你无法告诉数字引脚输出 1.5V 或 2.7V 或任何中间值。

模拟信号

模拟信号可以在一个范围内具有任何电压值。它不仅仅是“开”或“关”,而是连续且平滑地变化。把它想象成一个调光开关,可以将亮度设置为从完全关闭到完全明亮的任何位置,中间有无限个位置。

例如,模拟信号可以是 0V、0.5V、1.5V、2.8V、3.1V,或允许范围内的任何其他值。这种平滑的变化使你能够精确控制设备。

问题所在

挑战在于:大多数微控制器引脚都是数字的。它们只能输出 HIGH 或 LOW。但如果你想要做到以下几点呢:

将 LED 灯调暗到 50% 亮度,而不是仅仅完全开启或完全关闭(就像我们在快速开始的闪烁示例中做的那样)?或者控制伺服电机到 0° 到 180° 之间的任何位置?或者调节风扇速度或逐渐控制温度?

你需要某种行为类似于模拟输出的东西,但你只有数字引脚。这就是 PWM 发挥作用的地方。

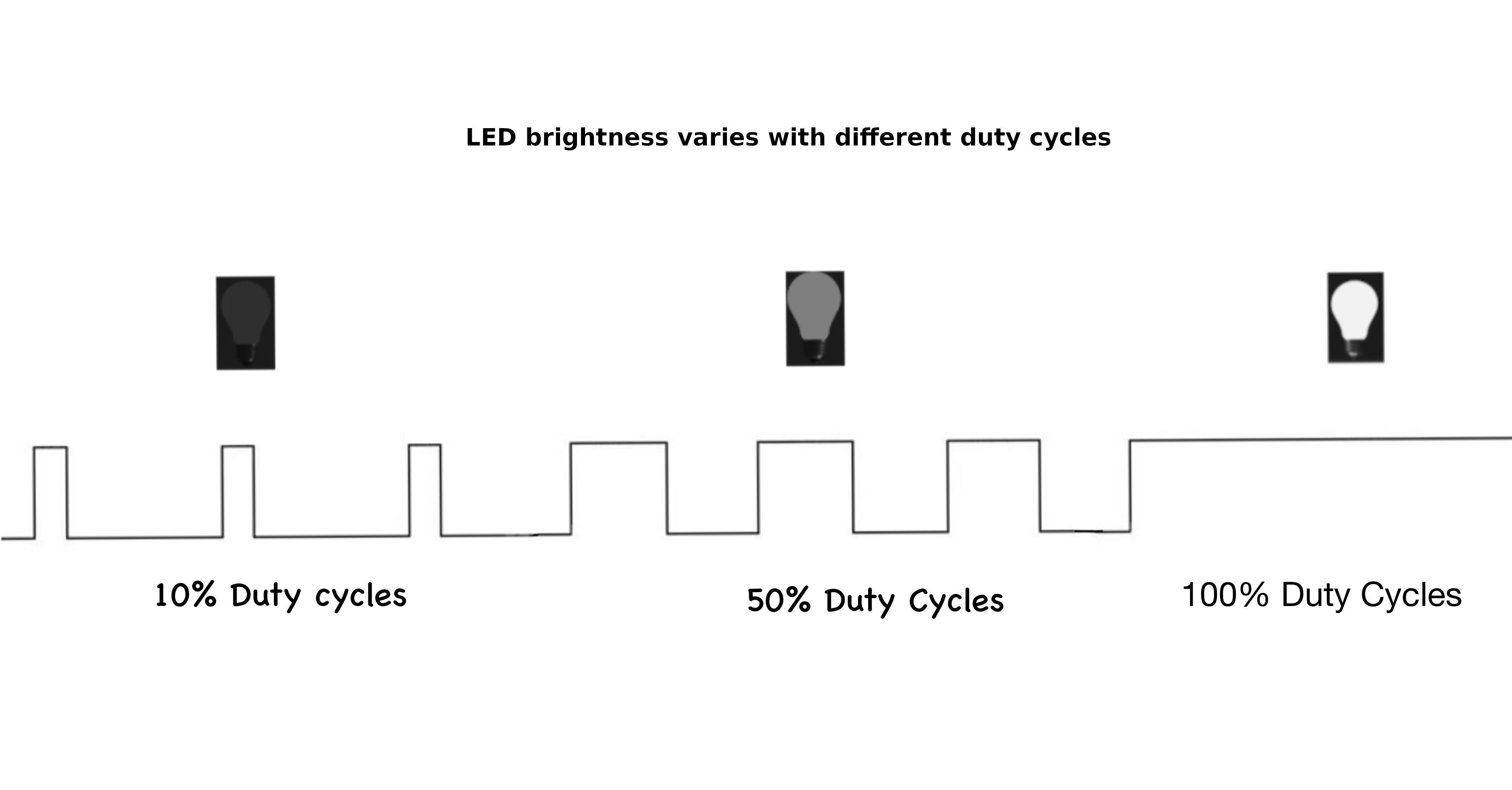

脉宽调制(PWM)

PWM 代表脉宽调制(Pulse Width Modulation)。它是一种使用在 HIGH 和 LOW 之间快速切换的数字信号来模拟模拟输出的技术。

PWM 不像真正的模拟信号那样提供稳定的电压(如 1.5V),而是在全电压和 0V 之间快速切换。通过控制信号保持在 HIGH 和 LOW 的时间长短,你可以控制输送到设备的平均功率或电压。

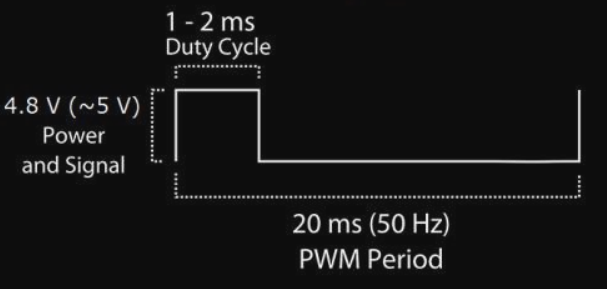

PWM 如何工作

PWM 的工作原理是以固定的频率发送在 HIGH 和 LOW 之间切换的方波信号。关键参数是“占空比”,即在一个完整周期内信号处于 HIGH 状态的时间百分比。

例如:

- 0% 占空比意味着信号始终为 LOW(平均 0V)。

- 50% 占空比意味着信号在 HIGH 和 LOW 的时间相等(3.3V 系统中平均 1.65V)。

- 75% 占空比意味着信号有 75% 的时间为 HIGH,25% 的时间为 LOW。

- 100% 占空比意味着信号始终为 HIGH(3.3V)。

这种切换发生得极快,通常每秒数百或数千次。速度如此之快,以至于 LED 和电机等设备响应的是平均电压,而不是单个脉冲。

示例用法:LED 调光

LED 闪烁得如此之快,以至于你的眼睛看不到单独的“开”和“关”脉冲,因此你只感知到平均亮度。较低的占空比使其看起来较暗,较高的占空比使其看起来较亮,即使 LED 始终在全电压和零电压之间切换。

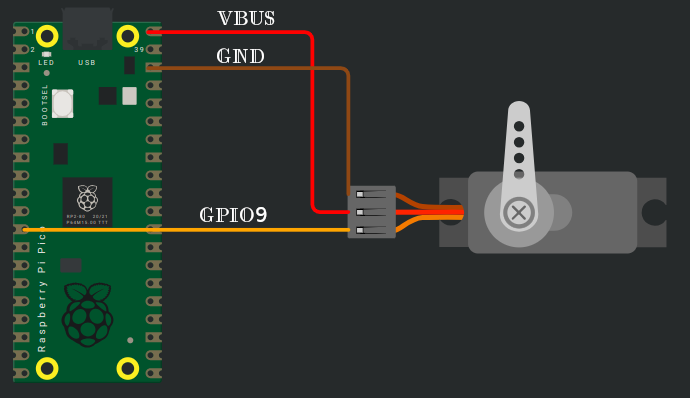

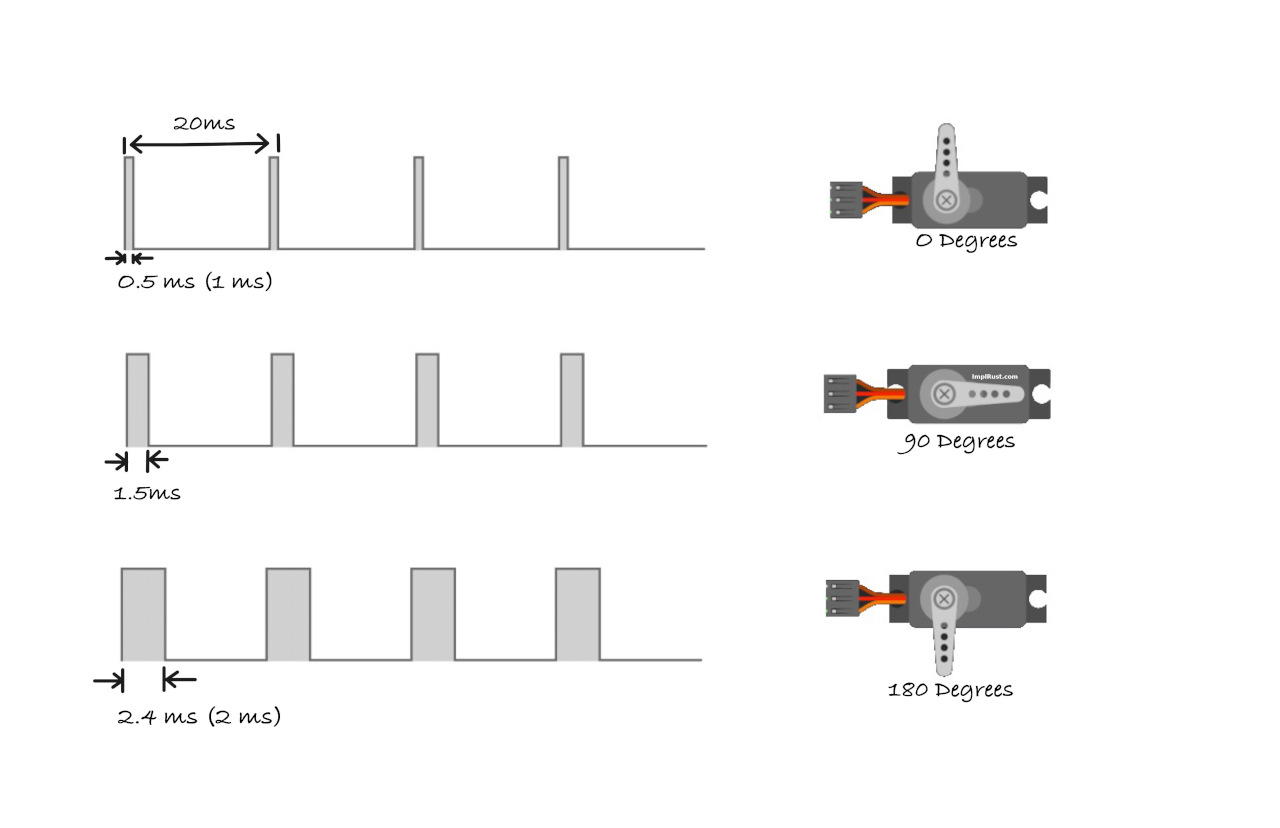

示例用法:控制伺服电机

伺服电机读取脉冲的宽度来决定其角度。它期望每 20 毫秒有一个脉冲,而脉冲宽度——0° 约为 1ms,90° 约为 1.5ms,180° 约为 2ms——告诉伺服电机移动到哪里。

周期和频率

在 PWM 中,周期和频率协同工作以决定信号在 HIGH 和 LOW 状态之间切换的速度,这直接影响控制的平滑度和有效性。

周期是一个“开-关”循环完成所需的总时间。

频率是一秒钟内完成的循环次数,以赫兹(Hz)为单位测量。频率是周期的倒数。因此,频率越高,周期越短,从而导致 HIGH 和 LOW 状态之间的切换越快。

\[ \text{Frequency (Hz)} = \frac{1}{\text{Period (s)}} \]

因此,如果周期为 1 秒,则频率将为 1Hz。

\[ 1 \text{Hz} = \frac{1 \text{ cycle}}{1 \text{ second}} = \frac{1}{1 \text{ s}} \]

例如,如果周期为 20ms(0.02s),频率将为 50Hz。

\[ \text{Frequency} = \frac{1}{20 \text{ ms}} = \frac{1}{0.02 \text{ s}} = 50 \text{ Hz} \]

根据每秒频率计算循环计数

计算循环计数的公式: \[ \text{Cycle Count} = \text{Frequency (Hz)} \times \text{Total Time (seconds)} \]

如果 PWM 信号的频率为 50Hz,这意味着它在一秒钟内完成 50 个循环。

仿真

这是一个交互式仿真。使用滑块调整占空比和频率,并观察脉冲宽度和 LED 亮度如何变化。方波的上半部分代表信号为高电平(开)时。下半部分代表信号为低电平(关)时。高电平部分的宽度随占空比而变化。

如果你在仿真中把占空比从“低调到高”再从“高调到低”,你应该会注意到 LED 呈现出一种调光效果。

PWM in Depth

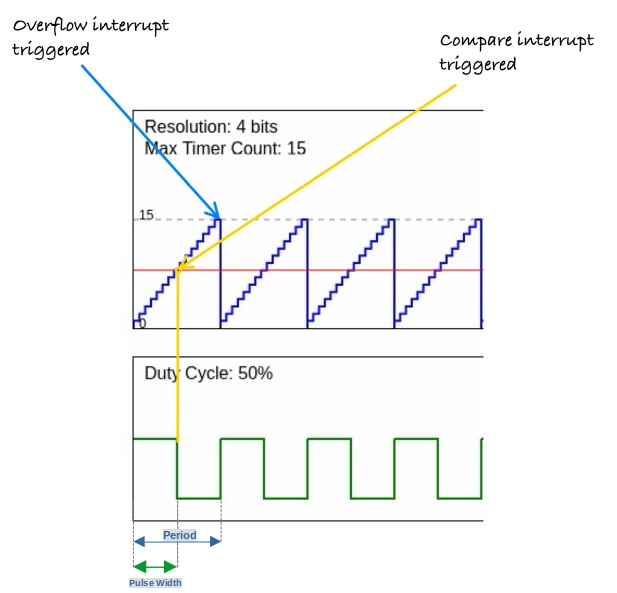

Timer Operation

The timer plays a key role in PWM generation. It counts from zero to a specified maximum value (stored in a register), then resets and starts the cycle over. This counting process determines the duration of one complete cycle, called the period.

Compare Value

The timer's hardware continuously compares its current count with a compare value (stored in a register). When the count is less than the compare value, the PWM signal stays HIGH; when the count exceeds the compare value, the signal goes LOW. By changing this compare value, you directly control the duty cycle.

PWM Resolution

Resolution refers to how precisely the duty cycle can be controlled. This is determined by the range of values the timer counts through in one complete cycle.

The timer counts from 0 to a maximum value based on the resolution. The higher the resolution, the more finely the duty cycle can be adjusted.

For a system with n bits of resolution, the timer counts from 0 to \(2^n - 1\), which gives \(2^n\) possible levels for the duty cycle.

For example:

- 8-bit resolution allows the timer to count from 0 to 255, providing 256 possible duty cycle levels.

- 10-bit resolution allows the timer to count from 0 to 1023, providing 1024 possible duty cycle levels.

Higher resolution gives more precise control over the duty cycle but requires the timer to count through more values within the same period. This creates a trade-off: to maintain the same frequency with higher resolution, you need a faster timer clock, or you must accept a lower frequency.

Simulation

You can modify the PWM resolution bits and duty cycle in this simulation. Adjusting the PWM resolution bits increases the maximum count but remains within the time period (it does not affect the duty cycle). Changing the duty cycle adjusts the on and off states accordingly, but it also stays within the period.

Relationship Between Duty Cycle, Frequency, and Resolution

This diagram shows how duty cycle, frequency, period, pulse width, and resolution work together in PWM generation. While it may seem a bit complex at first glance, breaking it down helps to clarify these concepts.

In this example, the timer resolution is 4 bits, meaning the timer counts from 0 to 15 (16 possible values). When the timer reaches its maximum value(i.e 15), an overflow interrupt is triggered (indicated by the blue arrow), and the counter resets to 0. The time it takes for the timer to count from 0 to its maximum value is called as "period".

The duty cycle is configured to 50%, meaning the signal remains high for half the period. At each step in the counting process, the timer compares its current count with the duty cycle's compare value. When the timer count exceeds this compare value (marked by the yellow arrow), the signal transitions from high to low. This triggers the compare interrupt, signaling the state change.

The time during which the signal is high is referred to as the pulse width.

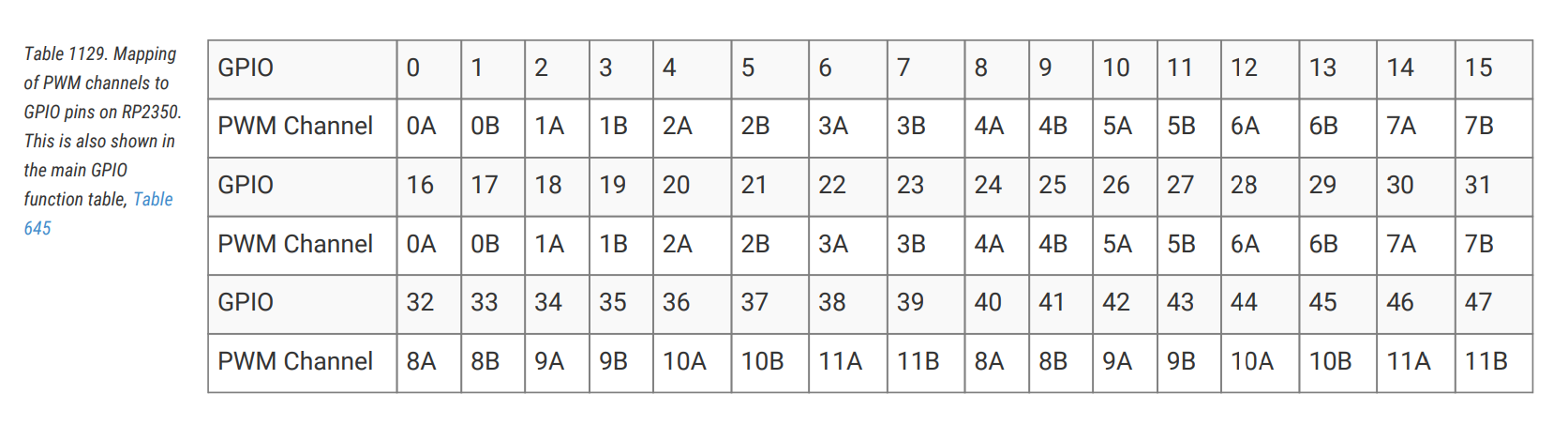

PWM Peripheral in RP2350

The RP2350 has a PWM peripheral with 12 PWM generators called slices. Each slice contains two output channels (A and B), giving you a total of 24 PWM output channels. For detailed specifications, see page 1076 of the RP2350 Datasheet.

Let's have a quick look at some of the key concepts.

PWM Generator (Slice)

A slice is the hardware block that generates PWM signals. Each of the 12 slices (PWM0–PWM11) is an independent timing unit with its own 16-bit counter, compare registers, control settings, and clock divider. This independence means you can configure each slice with different frequencies and resolutions.

Channel

Each slice contains two output channels: Channel A and Channel B. Both channels share the same counter, so they run at the same frequency and are synchronized. However, each channel has its own compare register, allowing independent duty cycle control. This lets you generate two related but distinct PWM signals from a single slice.

Mapping of PWM channels to GPIO Pins

Each GPIO pin connects to a specific slice and channel. You'll find the complete mapping table on page 1078 of the RP2350 Datasheet. For example, GP25 (the onboard LED pin) maps to PWM slice 4, channel B, labeled as 4B.

Initialize the PWM peripheral and get access to all slices:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut pwm_slices = hal::pwm::Slices::new(pac.PWM, &mut pac.RESETS); }

Get a reference to PWM slice 4 for configuration:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let pwm = &mut pwm_slices.pwm4; }

GPIO to PWM

I have created a small form that helps you figure out which GPIO pin maps to which PWM channel and also generates sample code.

Phase-Correct Mode

In standard PWM (fast PWM), the counter counts up from 0 to TOP, then immediately resets to 0. This creates asymmetric edges where the output changes at different points in the cycle.

Phase-correct PWM counts up to TOP, then counts back down to 0, creating a triangular waveform. The output switches symmetrically - once going up and once coming down. This produces centered pulses with edges that mirror each other, reducing electromagnetic interference and creating smoother transitions. The trade-off is that phase-correct mode runs at half the frequency of standard PWM for the same TOP value.

Configure PWM4 to operate in phase-correct mode for smoother output transitions.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pwm.set_ph_correct(); }

Get a mutable reference to channel B of PWM4 and direct its output to GPIO pin 25.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let channel = &mut pwm.channel_b; channel.output_to(pins.gpio25); }

Dimming LED

In this section, we will learn how to create a dimming effect(i.e. reducing and increasing the brightness gradually) for an LED using the Raspberry Pi Pico 2. First, we will dim the onboard LED, which is connected to GPIO pin 25 (based on the datasheet).

To make it dim, we use a technique called PWM (Pulse Width Modulation). You can refer to the intro to the PWM section here.

We will gradually increment the PWM's duty cycle to increase the brightness, then we gradually decrement the PWM duty cycle to reduce the brightness of the LED. This effectively creates the dimming LED effect.

The Eye

" Come in close... Closer...

Because the more you think you see... The easier it’ll be to fool you...

Because, what is seeing?.... You're looking but what you're really doing is filtering, interpreting, searching for meaning... "

Here's the magic: when this switching happens super quickly, our eyes can't keep up. Instead of seeing the blinking, it just looks like the brightness changes! The longer the LED stays ON, the brighter it seems, and the shorter it's ON, the dimmer it looks. It's like tricking your brain into thinking the LED is smoothly dimming or brightening.

Core Logic

What we will do in our program is gradually increase the duty cycle from a low value to a high value in the first loop, with a small delay between each change. This creates the fade-in effect. After that, we run another loop that decreases the duty cycle from high to low, again with a small delay. This creates the fade-out effect.

You can use the onboard LED, or if you want to see the dimming more clearly, use an external LED. Just remember to update the PWM slice and channel to match the GPIO pin you are using.

Simulation - LED Dimming with PWM

Here is a simulation to show the dimming effect on an LED based on the duty cycle and the High and Low parts of the square wave. I set the default speed very slow so it is clear and not annoying to watch. To start it, click the “Start animation” button. You can increase the speed by reducing the delay time and watching the changes.

LED Dimming on Raspberry Pi Pico with Embassy

Let's create a dimming LED effect using PWM on the Raspberry Pi Pico with Embassy.

Generate project using cargo-generate

By now you should be familiar with the steps. We use the cargo-generate command with our custom template, and when prompted, select Embassy as the HAL.

cargo generate --git https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-template.git --tag v0.3.1

Update Imports

Add the import below to bring the PWM types into scope:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use embassy_rp::pwm::{Pwm, SetDutyCycle}; }

Initialize PWM

Let's set up the PWM for the LED. Use the first line for the onboard LED, or uncomment the second one if you want to use an external LED on GPIO 16.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // For Onboard LED let mut pwm = Pwm::new_output_b(p.PWM_SLICE4, p.PIN_25, Default::default()); // For external LED connected on GPIO 16 // let mut pwm = Pwm::new_output_a(p.PWM_SLICE0, p.PIN_16, Default::default()); }

Main logic

In the main loop, we create the fade effect by increasing the duty cycle from 0 to 100 percent and then bringing it back down. The small delay between each step makes the dimming smooth. You can adjust the delay and observe how the fade speed changes.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { loop { for i in 0..=100 { Timer::after_millis(8).await; let _ = pwm.set_duty_cycle_percent(i); } for i in (0..=100).rev() { Timer::after_millis(8).await; let _ = pwm.set_duty_cycle_percent(i); } Timer::after_millis(500).await; } }

The full code

#![no_std] #![no_main] use embassy_executor::Spawner; use embassy_rp as hal; use embassy_rp::block::ImageDef; use embassy_rp::pwm::{Pwm, SetDutyCycle}; use embassy_time::Timer; //Panic Handler use panic_probe as _; // Defmt Logging use defmt_rtt as _; /// Tell the Boot ROM about our application #[unsafe(link_section = ".start_block")] #[used] pub static IMAGE_DEF: ImageDef = hal::block::ImageDef::secure_exe(); #[embassy_executor::main] async fn main(_spawner: Spawner) { let p = embassy_rp::init(Default::default()); // For Onboard LED let mut pwm = Pwm::new_output_b(p.PWM_SLICE4, p.PIN_25, Default::default()); // For external LED connected on GPIO 16 // let mut pwm = Pwm::new_output_a(p.PWM_SLICE0, p.PIN_16, Default::default()); loop { for i in 0..=100 { Timer::after_millis(8).await; let _ = pwm.set_duty_cycle_percent(i); } for i in (0..=100).rev() { Timer::after_millis(8).await; let _ = pwm.set_duty_cycle_percent(i); } Timer::after_millis(500).await; } } // Program metadata for `picotool info`. // This isn't needed, but it's recomended to have these minimal entries. #[unsafe(link_section = ".bi_entries")] #[used] pub static PICOTOOL_ENTRIES: [embassy_rp::binary_info::EntryAddr; 4] = [ embassy_rp::binary_info::rp_program_name!(c"led-dimming"), embassy_rp::binary_info::rp_program_description!(c"your program description"), embassy_rp::binary_info::rp_cargo_version!(), embassy_rp::binary_info::rp_program_build_attribute!(), ]; // End of file

Clone the existing project

You can clone the project I created and navigate to the external-led folder:

git clone https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-embassy-projects

cd pico2-embassy-projects/led-dimming

Dimming LED Program with RP HAL

rp-hal is an Embedded-HAL for RP series microcontrollers, and can be used as an alternative to the Embassy framework for pico.

This example code is taken from rp235x-hal repo (It also includes additional examples beyond just the blink examples):

"https://github.com/rp-rs/rp-hal/tree/main/rp235x-hal-examples"

The main code

#![no_std] #![no_main] use embedded_hal::delay::DelayNs; use hal::block::ImageDef; use rp235x_hal as hal; // Traig for PWM use embedded_hal::pwm::SetDutyCycle; //Panic Handler use panic_probe as _; // Defmt Logging use defmt_rtt as _; /// Tell the Boot ROM about our application #[unsafe(link_section = ".start_block")] #[used] pub static IMAGE_DEF: ImageDef = hal::block::ImageDef::secure_exe(); /// External high-speed crystal on the Raspberry Pi Pico 2 board is 12 MHz. /// Adjust if your board has a different frequency const XTAL_FREQ_HZ: u32 = 12_000_000u32; /// The minimum PWM value (i.e. LED brightness) we want const LOW: u16 = 0; /// The maximum PWM value (i.e. LED brightness) we want const HIGH: u16 = 25000; #[hal::entry] fn main() -> ! { // Grab our singleton objects let mut pac = hal::pac::Peripherals::take().unwrap(); // Set up the watchdog driver - needed by the clock setup code let mut watchdog = hal::Watchdog::new(pac.WATCHDOG); // Configure the clocks // // The default is to generate a 125 MHz system clock let clocks = hal::clocks::init_clocks_and_plls( XTAL_FREQ_HZ, pac.XOSC, pac.CLOCKS, pac.PLL_SYS, pac.PLL_USB, &mut pac.RESETS, &mut watchdog, ) .ok() .unwrap(); // The single-cycle I/O block controls our GPIO pins let sio = hal::Sio::new(pac.SIO); // Set the pins up according to their function on this particular board let pins = hal::gpio::Pins::new( pac.IO_BANK0, pac.PADS_BANK0, sio.gpio_bank0, &mut pac.RESETS, ); // Init PWMs let mut pwm_slices = hal::pwm::Slices::new(pac.PWM, &mut pac.RESETS); // Configure PWM4 let pwm = &mut pwm_slices.pwm4; pwm.set_ph_correct(); pwm.enable(); // Output channel B on PWM4 to GPIO 25 let channel = &mut pwm.channel_b; channel.output_to(pins.gpio25); let mut timer = hal::Timer::new_timer0(pac.TIMER0, &mut pac.RESETS, &clocks); loop { for i in LOW..=HIGH { timer.delay_us(8); let _ = channel.set_duty_cycle(i); } for i in (LOW..=HIGH).rev() { timer.delay_us(8); let _ = channel.set_duty_cycle(i); } timer.delay_ms(500); } } // Program metadata for `picotool info`. // This isn't needed, but it's recomended to have these minimal entries. #[unsafe(link_section = ".bi_entries")] #[used] pub static PICOTOOL_ENTRIES: [hal::binary_info::EntryAddr; 5] = [ hal::binary_info::rp_cargo_bin_name!(), hal::binary_info::rp_cargo_version!(), hal::binary_info::rp_program_description!(c"your program description"), hal::binary_info::rp_cargo_homepage_url!(), hal::binary_info::rp_program_build_attribute!(), ]; // End of file

Clone the existing project

You can clone the blinky project I created and navigate to the led-dimming folder to run this version of the blink program:

git clone https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-rp-projects

cd pico2-projects/led-dimming

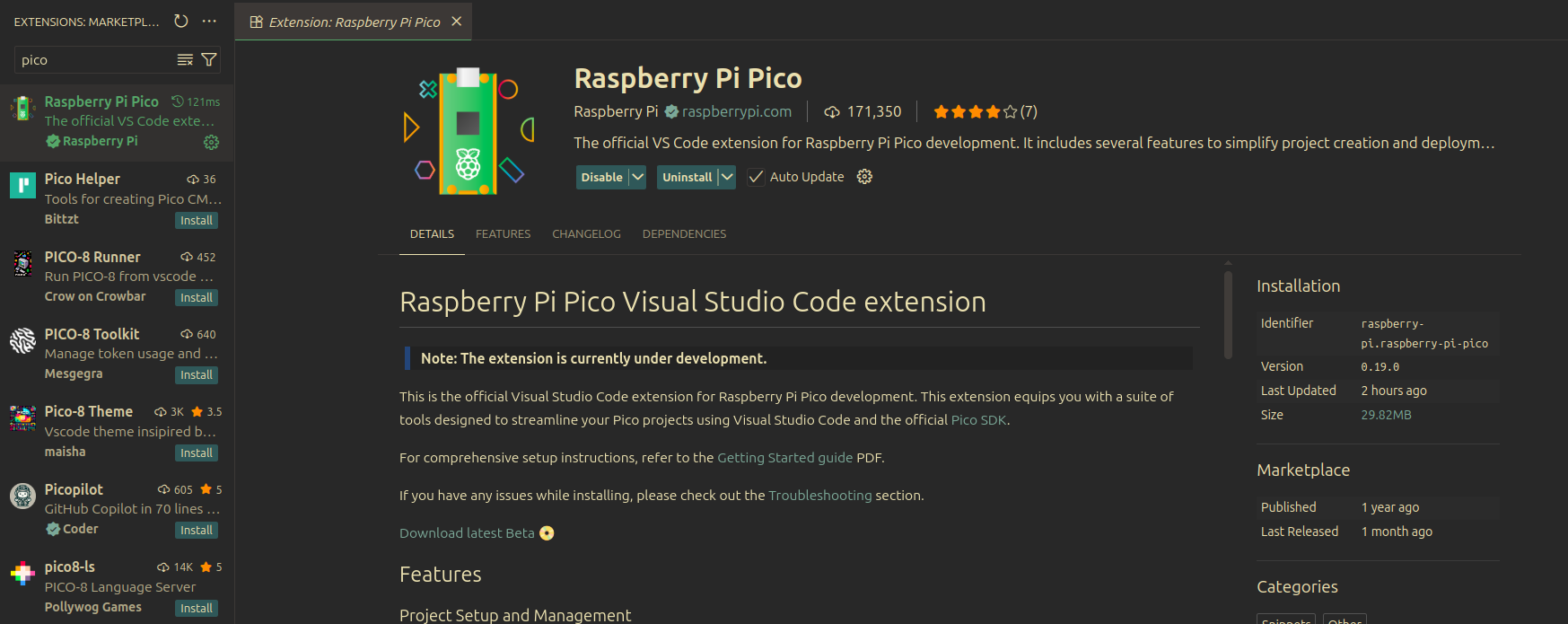

Creating a Rust Project for Raspberry Pi Pico in VS Code (with extension)

We've already created the Rust project for the Pico manually and through the template. Now we are going to try another approach: using the Raspberry Pi Pico extension for VS Code.

Using the Pico Extension

In Visual Studio Code, search for the extension "Raspberry Pi Pico" and ensure you're installing the official one; it should have a verified publisher badge with the official Raspberry Pi website. Install that extension.

Just installing the extension might not be enough though, depending on what's already on your machine. On Linux, you'll likely need some basic dependencies:

sudo apt install build-essential libudev-dev

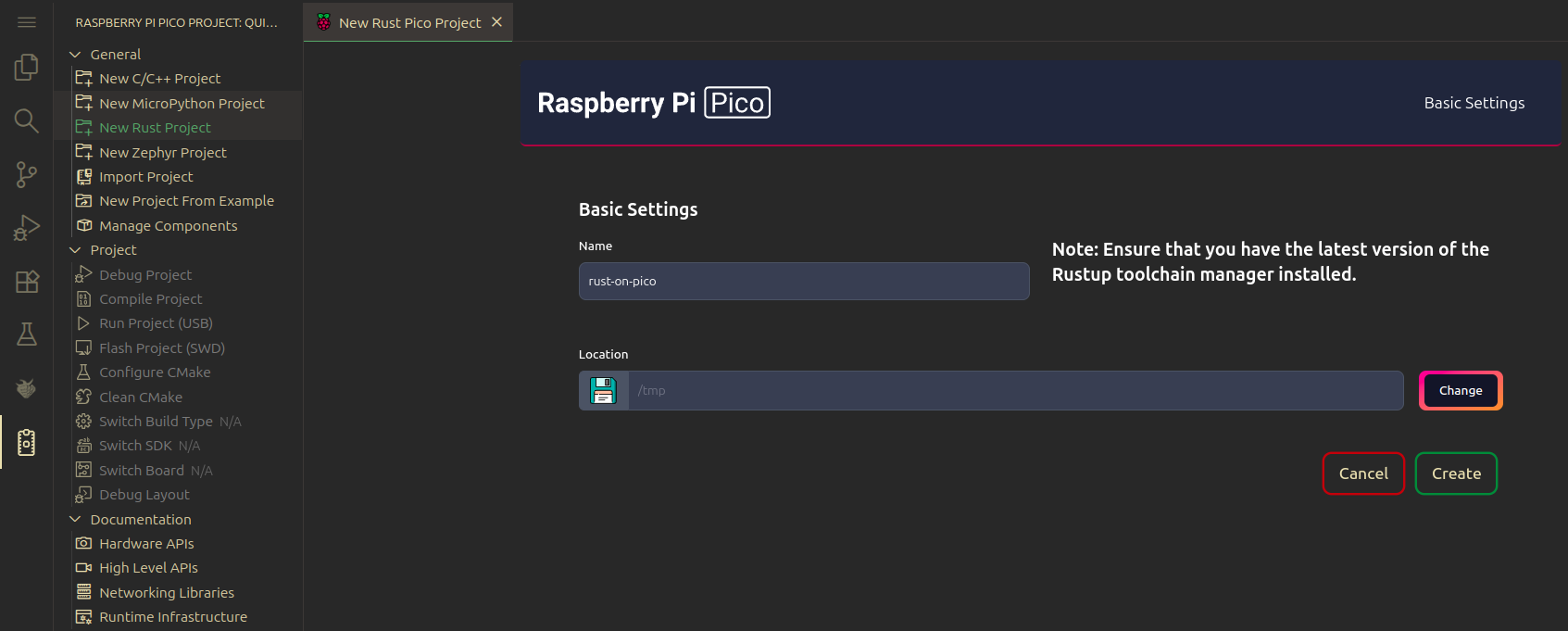

Create Project

Let's create the Rust project with the Pico extension in VS Code. Open the Activity Bar on the left and click the Pico icon. Then choose “New Rust Project.”

Since this is the first time setting up, the extension will download and install the necessary tools, including the Pico SDK, picotool, OpenOCD, and the ARM and RISC-V toolchains for debugging.

Project Structure

If the project was created successfully, you should see folders and files like this:

Running the Program

Now you can simply click "Run Project (USB)" to flash the program onto your Pico and run it. Don't forget to press the BOOTSEL button when connecting your Pico to your computer. Otherwise, this option will be in disabled state.

.png)

Once flashing is complete, the program will start running immediately on your Pico. You should see the onboard LED blinking.

按钮

既然我们已经知道如何闪烁 LED,让我们来学习如何读取按钮输入。这将使我们能够与 Raspberry Pi Pico 交互,并让我们的程序对我们的操作做出响应。

按钮是一个小的轻触开关。你会在大多数初学者电子套件中找到这些。当你按下它时,内部的两个引脚接触,电路闭合。当你松开它时,引脚分离,电路再次断开。你的程序可以读取这种开或关的状态,并据此执行某些操作。

轻触按钮如何工作

轻触按钮有四个引脚,成对排列。从上方看按钮,引脚形成一个矩形。按钮每侧的两个引脚在内部是电气连接的。

我稍后会更新这一部分,提供更清晰的图表,更明确地显示内部连接。目前,这个插图足以理解这个概念。浅色线表示左侧的引脚彼此连接,右侧的引脚也是如此。当按下按钮时,左侧和右侧连接在一起。

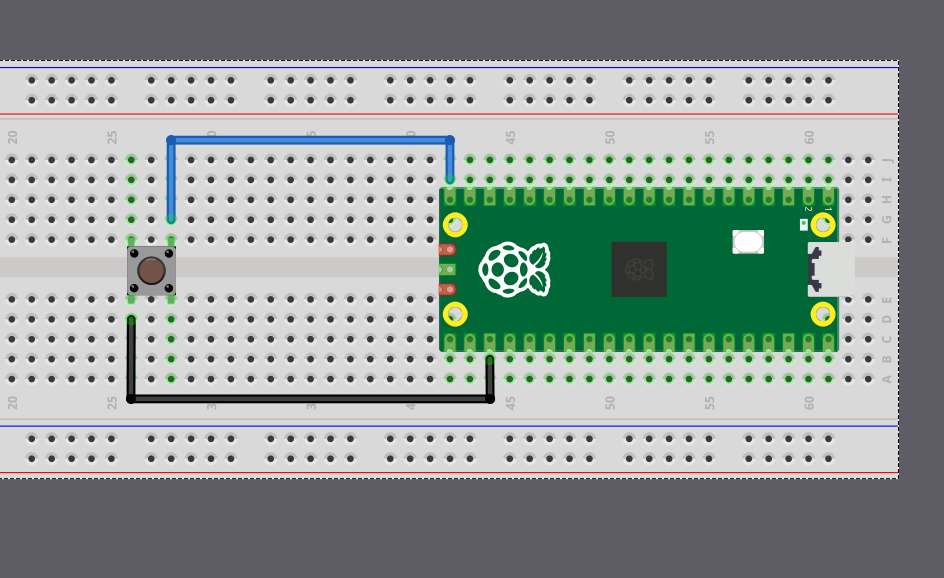

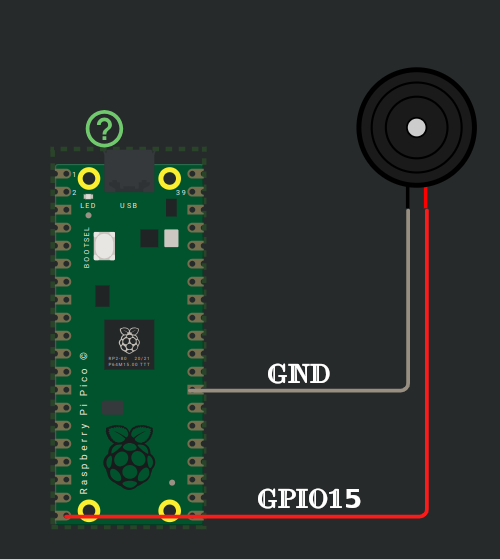

将按钮连接到 Pico

将按钮的一侧连接到接地(Ground),另一侧连接到通用输入输出(GPIO)引脚(例如 GPIO 15)。当按下按钮时,两侧在内部连接,GPIO 15 引脚被拉低。我们可以在代码中检查引脚是否被拉低,并据此触发动作。

等等。当按钮未被按下时会发生什么?GPIO 引脚现在读取的是什么电压或电平?为了在逻辑上讲得通,引脚应该处于高电平(High)状态,这样我们才能将低电平(Low)状态检测为按钮按下。但是,如果电路中没有其他东西,GPIO 引脚将处于所谓的浮动状态(floating state)。这是不可靠的,即使没有按下按钮,引脚也可能随机地在高电平及低电平之间切换。我们该如何解决这个问题?让我们在下一节中看看。

Pull-up and Pull-down Resistors

When working with buttons, switches, and other digital inputs on your Raspberry Pi Pico, you'll quickly encounter a curious problem: what happens when nothing is connected to an input pin? The answer might surprise you; the pin becomes "floating," picking up electrical noise and giving you random, unpredictable readings. This is where pull-up and pull-down resistors come to the rescue.

The Floating Pin Problem

Imagine you connect a button directly to a GPIO pin on your Pico. When the button is pressed, it connects the pin to ground (0V). When released, you might expect the pin to read as HIGH, but it doesn't work that way. Instead, the pin is disconnected from everything. It's floating in an undefined state, acting like an antenna that picks up electrical noise from nearby circuits, your hand, or even radio waves in the air.

This floating state will cause your code to read random values, making your button appear to press itself or behave erratically. We need a way to give the pin a default, predictable state.

By the way, you can also connect the button the other way around; connecting one side to 3.3V instead of ground (though I wouldn't recommend this for the RP2350, and I'll explain why shortly). However, you'll face the same issue. When the button is pressed, it connects to the High state. When released, you might expect it to go Low, but instead it's in a floating state again.

What Are Pull-up and Pull-down Resistors?

Pull-up and pull-down resistors are simple solutions that ensure a pin always has a known voltage level, even when nothing else is driving it.

Pull-up resistor: Connects the pin to the positive voltage (3.3V on the Pico) through a resistor. This "pulls" the pin HIGH by default. When you press a button that connects the pin to ground, the pin reads LOW.

Pull-down resistor: Connects the pin to ground (0V) through a resistor. This "pulls" the pin LOW by default. When you press a button that connects the pin to 3.3V, the pin reads HIGH.

How Pull-up Resistors Work

Let's look at a typical button circuit with a pull-up resistor:

When the button is not pressed, current flows through the resistor to the GPIO pin, holding it at 3.3V (HIGH). When you press the button, you create a direct path to ground. Since electricity follows the path of least resistance, current flows through the button to ground instead of to the pin, and the pin reads LOW.

How Pull-down Resistors Work

A pull-down resistor works in the opposite direction:W

When the button is not pressed, the GPIO pin is connected to ground through the resistor, reading LOW. When pressed, the button connects the pin directly to 3.3V, and the pin reads HIGH.

Internal Pull Resistors

The Raspberry Pi Pico has built-in pull-up and pull-down resistors on every GPIO pin. You don't need to add external resistors for basic button inputs. You can enable them in software.

Using Pull Resistors in Embedded Rust

Let's see how to configure internal pull resistors when setting up a button input on the Pico.

As you can see in the diagram, when we enable the internal pull-up resistor, the GPIO pin is pulled to 3.3V by default. The resistor sits inside the Pico chip itself, so we don't need any external components; just the button connected between the GPIO pin and ground.

Here's how to set it up in code:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let button = Input::new(p.PIN_16, Pull::Up); // Read the button state if button.is_low() { // Button is pressed (connected to ground) // Do something } }

With a pull-up resistor enabled, the GPIO pin gets pulled to HIGH voltage by default. When you press the button, it connects the pin to ground, and brings the pin LOW. So the logic is: button not pressed = HIGH, button pressed = LOW.

Setting up a Button with a Pull-down Resistor

Here's similar code, but this time we use the internal pull-down resistor. With pull-down, the pin is pulled LOW by default. When the button is pressed, connecting the pin to 3.3V, it reads HIGH.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let button = Input::new(p.PIN_16, Pull::Down); // Read the button state if button.is_high() { // Button is pressed (connected to 3.3V) // Do something } }

Note: There's a hardware bug (E9) in the initial RP2350 chip released in 2024 that affects internal pull-down resistors.

The bug causes the GPIO pin to read HIGH even when the button isn't pressed, which is the opposite of what should happen. You can read more about this issue in this blog post.

The bug was fixed in the newer RP2350 A4 chip revision. If you're using an older chip, avoid using

Pull::Downin your code. Instead, you can use an external pull-down resistor and setPull::Nonein the code.

With a pull-down resistor enabled, the button should connect to 3.3V when pressed. The pin reads LOW when not pressed, and HIGH when pressed.

Using a Floating Input

You can also configure a pin without any internal pull resistor:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let button = Input::new(p.PIN_16, Pull::None); }

However, as we discussed earlier, floating inputs are unreliable for buttons because they pick up electrical noise and read random values. This option is only useful when you have an external pull-up or pull-down resistor in your circuit, or when connecting to devices that actively drive the pin HIGH or LOW (like some sensors).

LED on Button Press

Let's build a simple project that turns on an LED whenever the button is pressed. You can use an external LED or the built in LED. Just change the LED pin number in the code to match the one you are using.

We will start by creating a new project with cargo generate and our template.

In your terminal, type:

cargo generate --git https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-template.git --tag v0.3.1

Button as Input

So far, we've been using the Output struct because our Pico was sending signals to the LED. This time, the Pico will receive a signal from the button, so we'll configure it as an Input.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let button = Input::new(p.PIN_15, Pull::Up); }

We've connected one side of the button to GPIO 15. The other side is connected to Ground. This means when we press the button, the pin gets pulled to the LOW state. As we discussed earlier, without a pull resistor, the input would be left in a floating state and read unreliable values. So we enable the internal pull-up resistor to keep the pin HIGH by default.

Led as Output

We configure the LED pin as an output, starting in the LOW state (off). If you're using an external LED, uncomment the first line for GPIO 16. If you're using the Pico's built-in LED, use GPIO 25 as shown. Just make sure your circuit matches whichever pin you choose.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // let mut led = Output::new(p.PIN_16, Level::Low); let mut led = Output::new(p.PIN_25, Level::Low); }

Main loop

Now in a loop, we constantly check if the button is pressed by testing whether it's in the LOW state. We add a small 5-millisecond delay between checks to avoid overwhelming the system. When the button reads LOW (pressed), we set the LED pin HIGH to turn it on, then wait for 3 seconds so we can visually observe it. You can adjust this delay to your preference.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { loop { if button.is_low() { defmt::info!("Button pressed"); led.set_high(); Timer::after_secs(3).await; } else { led.set_low(); } Timer::after_millis(5).await; } }

Debounce: If you reduce the delay, you might notice that sometimes a single button press triggers multiple detections. This is called "button bounce". When you press a physical button, the metal contacts inside briefly bounce against each other, creating multiple electrical signals in just a few milliseconds. In this example, the 3-second LED delay effectively masks any bounce issues, but in applications where you need to count individual button presses accurately, you'll need debouncing logic.

We also log "Button pressed" using defmt. If you're using a debug probe, use the cargo embed --release command to see these logs in your terminal.

The Full code

#![no_std] #![no_main] use embassy_executor::Spawner; use embassy_rp::block::ImageDef; use embassy_rp::gpio::Pull; use embassy_rp::{ self as hal, gpio::{Input, Level, Output}, }; use embassy_time::Timer; //Panic Handler use panic_probe as _; // Defmt Logging use defmt_rtt as _; /// Tell the Boot ROM about our application #[unsafe(link_section = ".start_block")] #[used] pub static IMAGE_DEF: ImageDef = hal::block::ImageDef::secure_exe(); #[embassy_executor::main] async fn main(_spawner: Spawner) { let p = embassy_rp::init(Default::default()); let button = Input::new(p.PIN_15, Pull::Up); // let mut led = Output::new(p.PIN_16, Level::Low); let mut led = Output::new(p.PIN_25, Level::Low); loop { if button.is_low() { defmt::info!("Button pressed"); led.set_high(); Timer::after_secs(3).await; } else { led.set_low(); } Timer::after_millis(5).await; } } // Program metadata for `picotool info`. // This isn't needed, but it's recomended to have these minimal entries. #[unsafe(link_section = ".bi_entries")] #[used] pub static PICOTOOL_ENTRIES: [embassy_rp::binary_info::EntryAddr; 4] = [ embassy_rp::binary_info::rp_program_name!(c"button"), embassy_rp::binary_info::rp_program_description!(c"your program description"), embassy_rp::binary_info::rp_cargo_version!(), embassy_rp::binary_info::rp_program_build_attribute!(), ]; // End of file

Clone the existing project

You can clone (or refer) project I created and navigate to the button folder.

git clone https://github.com/ImplFerris/pico2-embassy-projects

cd pico2-embassy-projects/button

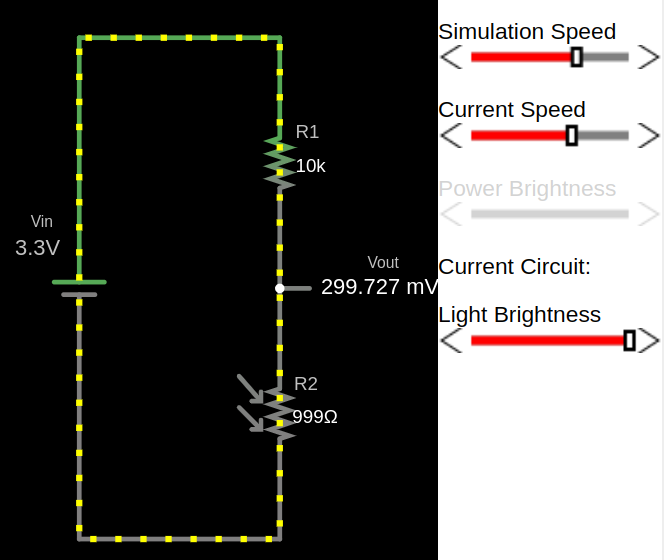

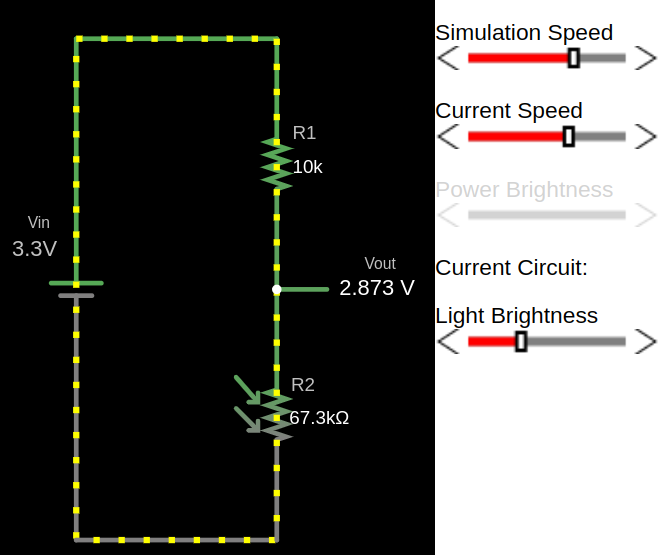

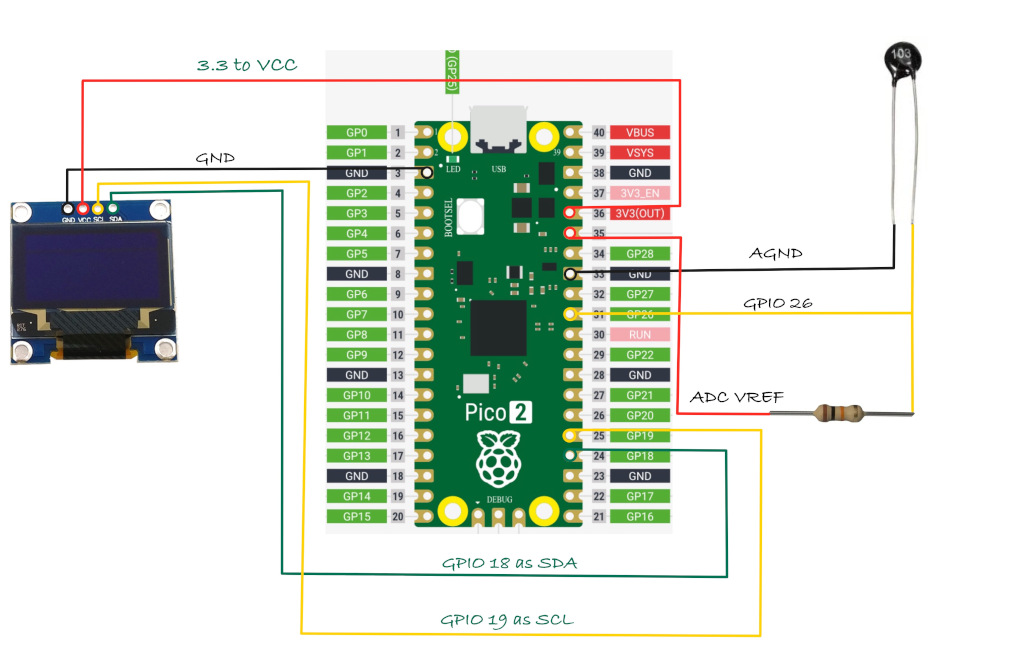

Voltage Divider

A voltage divider is a simple circuit that reduces a higher input voltage to a lower output voltage using two resistors connected in series. You might need a voltage divider from time to time when working with sensors or modules that output higher voltages than your microcontroller can safely handle.

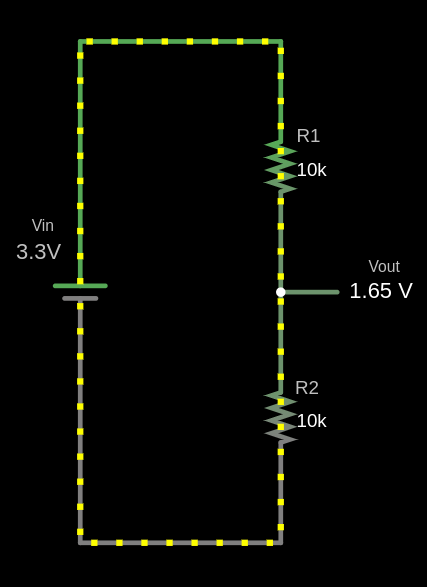

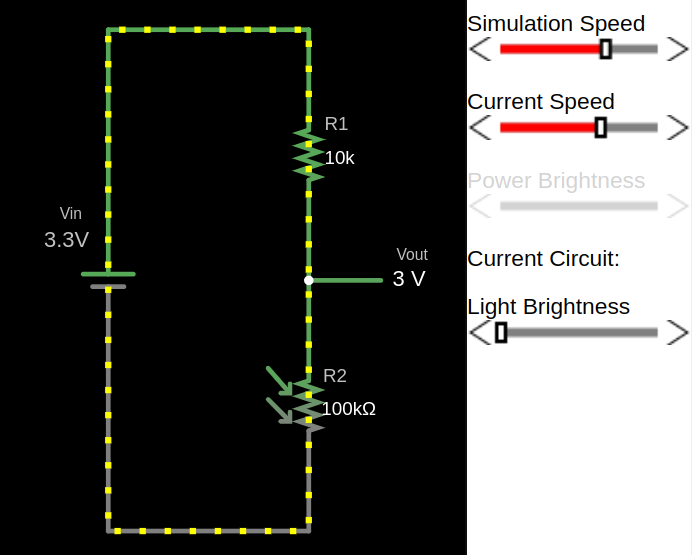

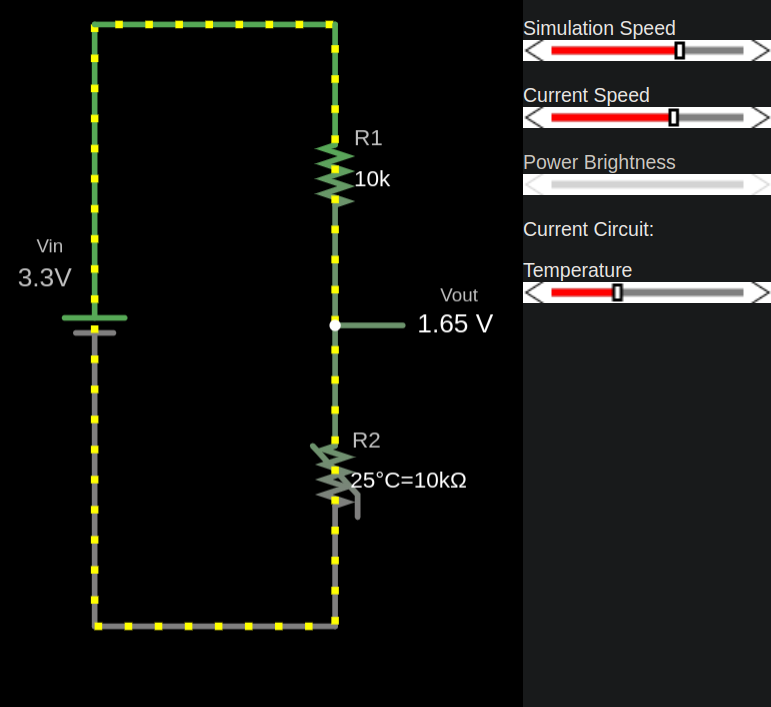

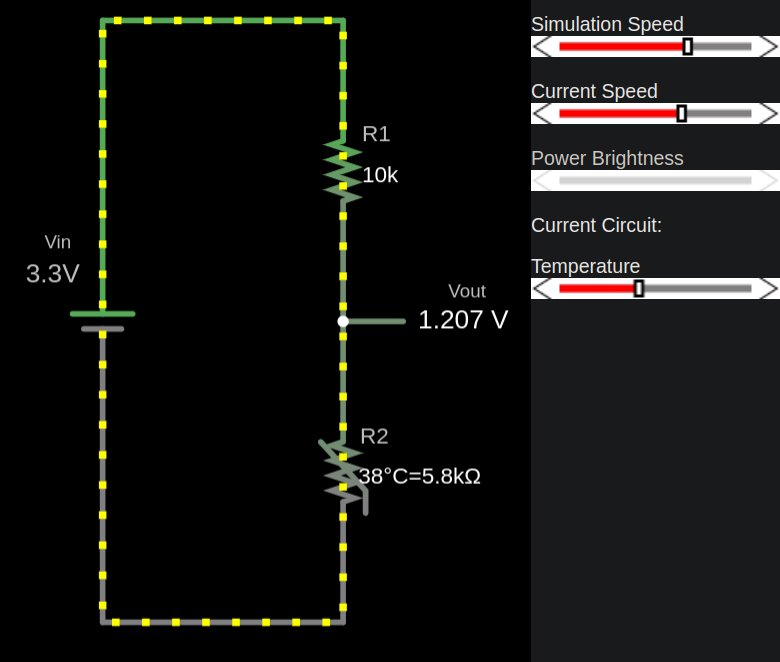

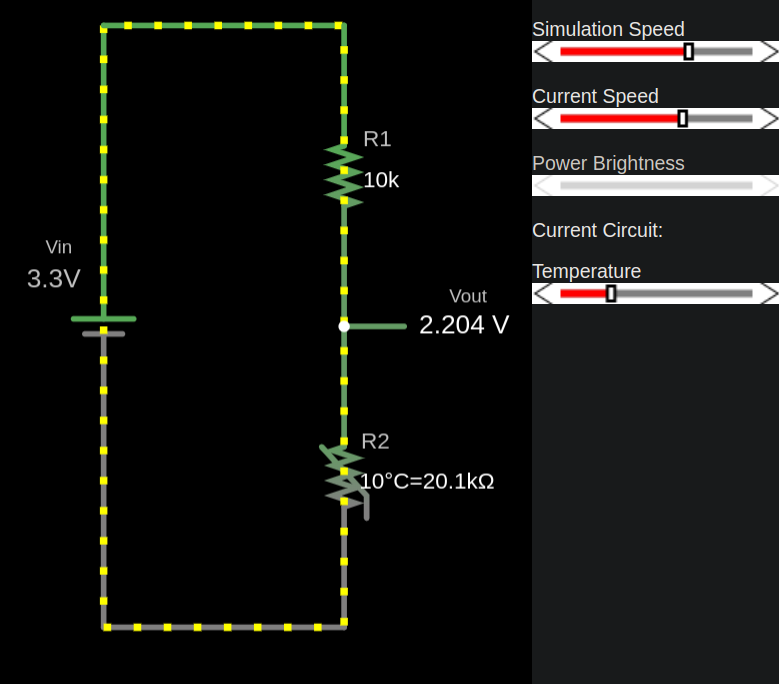

The resistor connected to the input voltage is called \( R_{1} \), and the resistor connected to ground is called \( R_{2} \). The output voltage \( V_{out} \) is measured at the point between \( R_{1} \) and \( R_{2} \), and it will be a fraction of the input voltage \( V_{in} \).

Circuit

The output voltage (Vout) is calculated using this formula:

\[ V_{out} = V_{in} \times \frac{R_2}{R_1 + R_2} \]

Example Calculation for \( V_{out} \)

Given:

- \( V_{in} = 3.3V \)

- \( R_1 = 10 k\Omega \)

- \( R_2 = 10 k\Omega \)

Substitute the values:

\[ V_{out} = 3.3V \times \frac{10 k\Omega}{10 k\Omega + 10 k\Omega} = 3.3V \times \frac{10}{20} = 3.3V \times 0.5 = 1.65V \]

The output voltage \( V_{out} \) is 1.65V.

fn main() { // You can edit the code // You can modify values and run the code let vin: f64 = 3.3; let r1: f64 = 10000.0; let r2: f64 = 10000.0; let vout = vin * (r2 / (r1 + r2)); println!("The output voltage Vout is: {:.2} V", vout); }

Use cases

Voltage dividers are used in applications like potentiometers, where the resistance changes as the knob is rotated, adjusting the output voltage. They are also used to measure resistive sensors such as light sensors and thermistors, where a known voltage is applied, and the microcontroller reads the voltage at the center node to determine sensor values like temperature.

Voltage Divider Simulation

Formula: Vout = Vin × (R2 / (R1 + R2))

Filled Formula: Vout = 3.3 × (10000 / (10000 + 10000))

Output Voltage (Vout): 1.65 V

Simulator in Falstad website

I used the website https://www.falstad.com/circuit/ to create the diagram. It's a great tool for drawing circuits. You can download the file I created, voltage-divider.circuitjs.txt, and import it to experiment with the circuit.

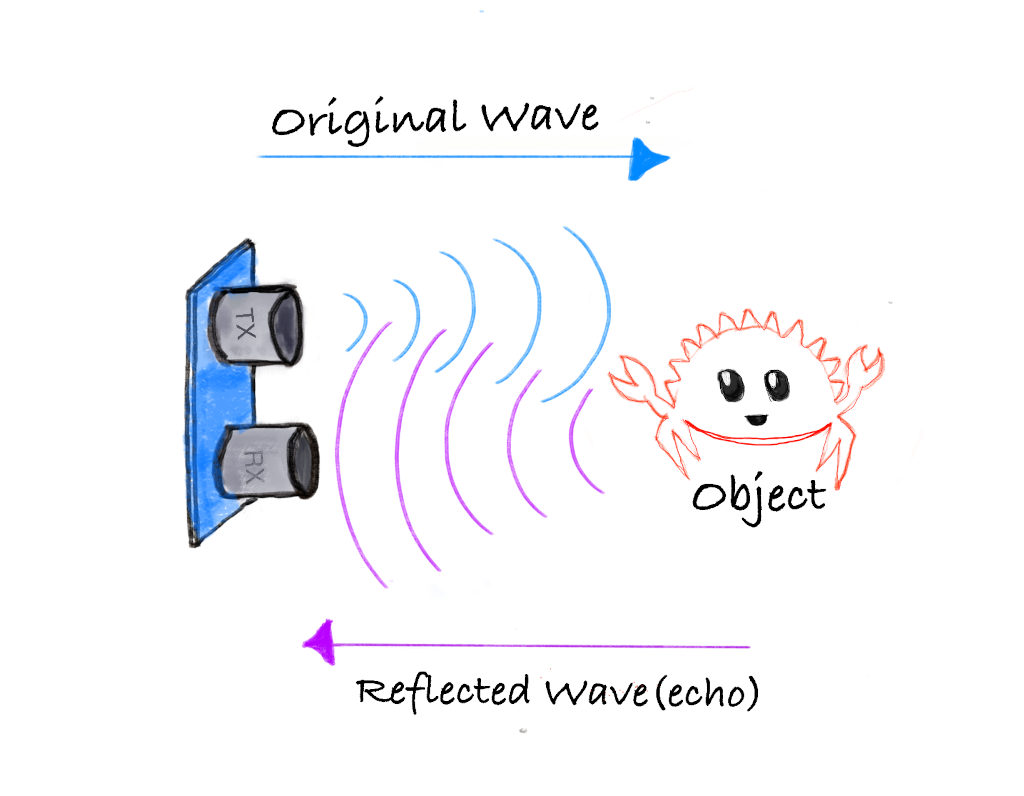

Bat Beacon: Distance Sensor Project 🦇

If you've seen the Batman Begins movie, you'll remember the scene where Batman uses a device that emits ultrasonic signals to summon a swarm of bats. It's one of the coolest gadgets in his arsenal! While we won't be building a bat-summoning beacon today, we will be working with the similar ultrasonic technology.

Ultrasonic

Ultrasonic waves are sound waves with frequencies above 20,000 Hz, beyond what human ears can detect. But many animals can. Bats use ultrasonic waves to fly in the dark and avoid obstacles. Dolphins use them to communicate and to sense objects underwater.

Ultrasonic Technology Around You

Humans have borrowed this natural sonar principle for everyday inventions:

- Car parking sensors use ultrasonic sensors to detect obstacles when you reverse. As you get closer to an object, the beeping gets faster.

- Submarines use sonar to navigate and detect underwater objects

- Medical ultrasound allows doctors to see inside the human body

- Automatic doors and robot navigation rely on ultrasonic distance sensing

Today, you'll build your own distance sensor using an ultrasonic module; sending out sound waves, measuring how long they take to bounce back, and calculating distance.

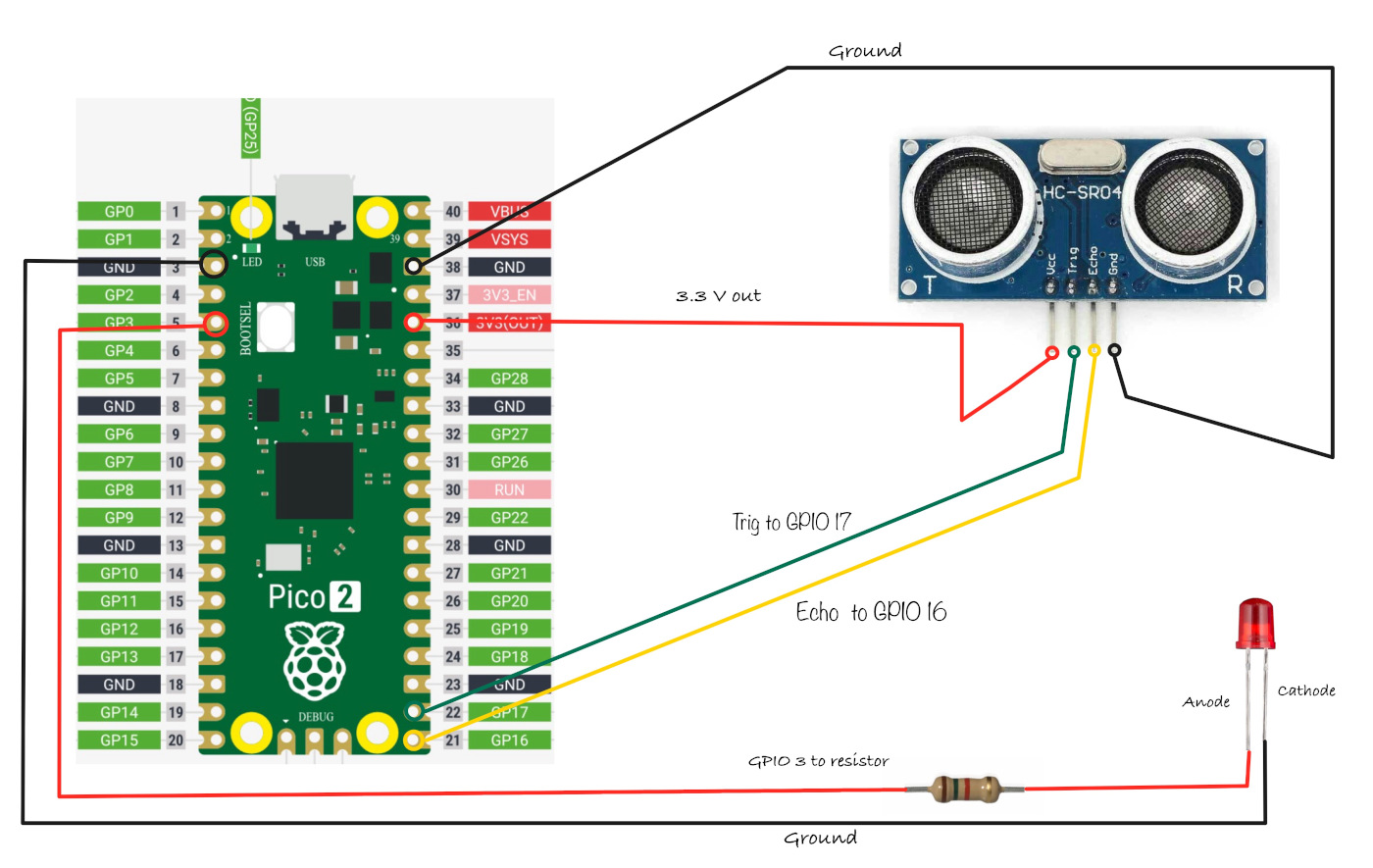

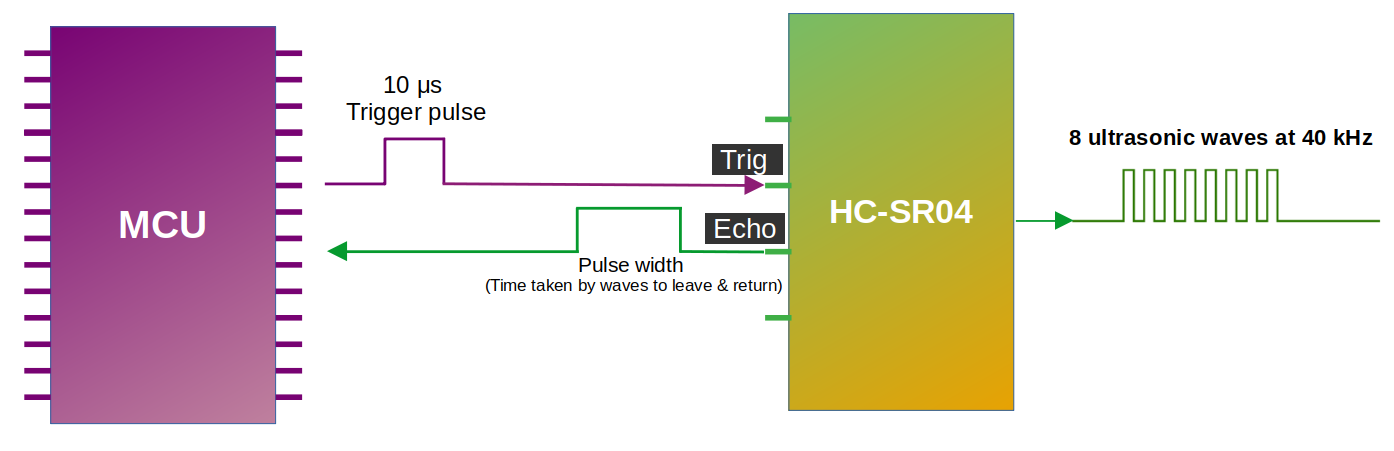

Meet the Hardware

The HC-SR04+ is a simple and low cost ultrasonic distance sensor. It can measure distances from about 2 cm up to 400 cm. It works by sending out a short burst of ultrasonic sound and then listening for the echo. By measuring how long the echo takes to return, the sensor can calculate how far the object is.

Important Note about Variants:

The HC-SR04 normally operates at 5V, which can be problematic for the Raspberry Pi Pico. If possible, purchase the HC-SR04+ version, which works with both 3.3V and 5V, making it more suitable for the Pico.

Why This Matters: The HC-SR04's Echo pin outputs a 5V signal, but the Pico's GPIO pins can only safely handle 3.3V. Connecting 5V directly to the Pico could damage it.

Your Options:

- Buy the HC-SR04+ variant (recommended and easiest solution)

- Use a voltage divider on the Echo pin to reduce the 5V signal to 3.3V

- Use a logic level converter to safely step down the voltage

- Power the HC-SR04 with 3.3V (not recommended, as it may work unreliably or not at all)

In this project, we'll build a proximity detector that gradually brightens an LED as objects get closer. When the sensor detects something within 30 cm, the LED will glow brighter using PWM. You can change the distance value if you want to try different ideas.

Prerequisites

Before starting, get familiar with yourself on these topics

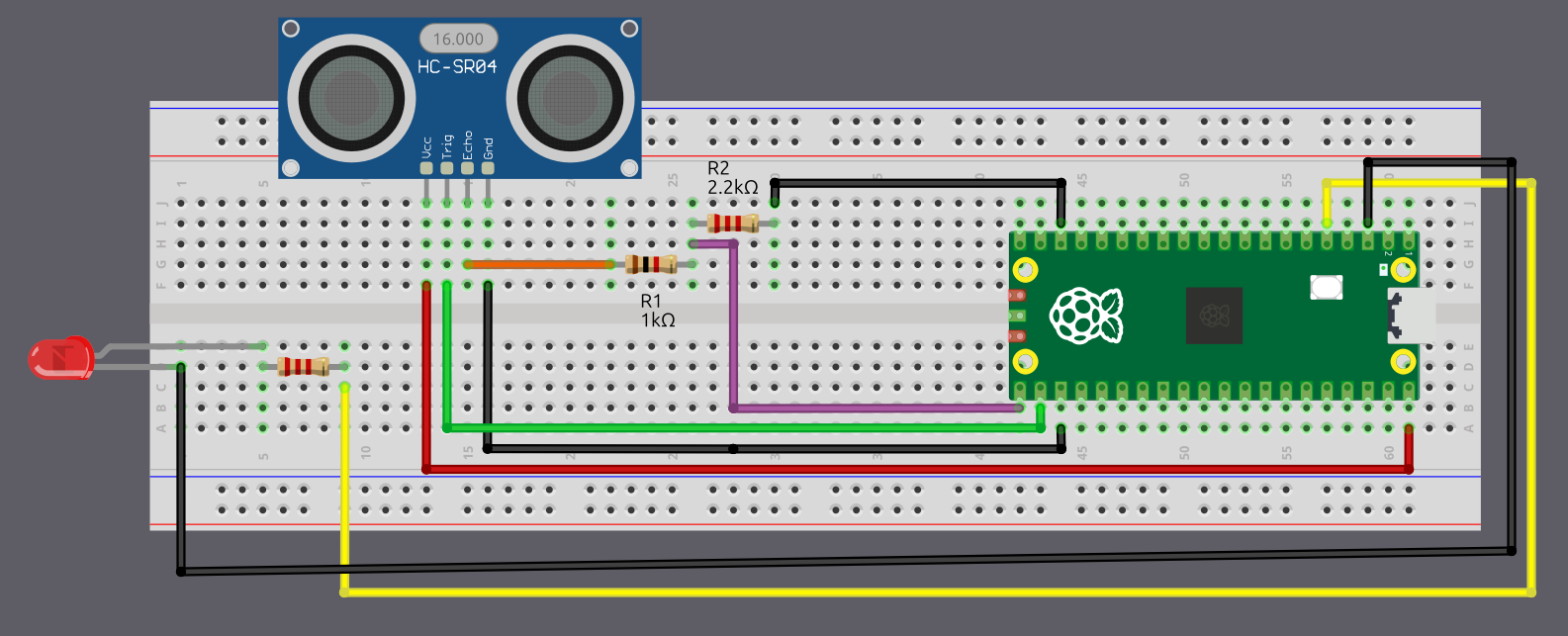

Hardware Requirements

To complete this project, you will need:

- HC-SR04+ or HC-SR04 Ultrasonic Sensor

- Breadboard

- Jumper wires

- External LED (You can also use the onboard LED, but you'll need to modify the code accordingly)

- If you are using the standard HC-SR04 module that operates at 5V, you will need two resistors (1kΩ and 2kΩ or 2.2kΩ) to form a voltage divider.